We all showed up at Screen Gems Studio in Atlanta with anticipation. We were there for an in-person audition for a network television show. In-person auditions have become rare in the high technology world of today’s television acting. What was once an actor’s pride, to enter a room with producers, directors, and casting directors and “win the room” has now been relegated to putting your audition on tape and emailing it to either your agents or a pay subscriber service (which I refuse to do). Things change.

The opportunity is a USA network episodic in its second season. The character, Mike runs an old dive bar somewhere in North Philadelphia. Mike acts as a counselor to the young actor playing one of the leads, Neil, whose father and Mike were friends in Vietnam. In terms of a character, Mike was interesting, a character with layers and the possibility of recurring work. Mike was worth the time and effort.

Long past the excitement of “being on television,” this opportunity from a business perspective meant a boost in pension pay, earnings toward family healthcare, a payday and perhaps several more if Mike recurred. It was strictly business.

But then it turned into something else.

Walking into the audition waiting area, an impromptu reunion took place. The boys were there.

Gordon and I worked together a few years ago on the Television Movie Game of Your Life. We had fun and most of our scenes together. I like Gordon’s work. I like Gordon. He’s a great guy to spend 14 hours a day with for several weeks making television.

Charles was the odds on favorite for the job. He has the look. Television is about the look. The producer’s creed is “We can teach someone to act. We can’t teach a look.” Charles wears a white beard. He’s short in stature and talks with a comforting tone. I’ve known Charles since we both worked on In The Heat Of The Night in the 1990s.

Alonzo, I don’t know. We share the same agent. Seems like a nice guy. He laughed a lot at the stories flying around the room.

Tony I’ve never worked with. He had a nice run on a Tyler Perry show. He’s been searching for the next opportunity ever since.

We were all there to read for Mike. That’s the business. There were five of us for the one job. We all had a 20% chance.

The job would begin shooting one week later. We all knew whoever got the job would be getting “the phone call” within twenty-four hours. The others would not. I always say not getting the job is like the country western song, "If your phone don’t ring, you’ll know it’s me.”

The Director was an hour late. Veterans to the “hurry up and wait,” aspect of “the business” we took it in stride and took time to catch up. We were all there for the same job, but we’ve been in the business long enough to not let that fact get in the way of our friendships. We laughed and told stories. Gordon and I caught up on life. Charles told stories of his civil rights days. Alonzo laughed a lot. Tony told stories but fretted over the job. It showed in his eyes.

I enjoyed the experience. It had been a while. Over the last few years, since moving back from Los Angeles, business opportunities, production of a documentary film, and writing another book had taken me in different directions. I had managed to stay in the game with Game of Your Life, Drop Dead Diva, Reckless, Queen and Slim, Containment and commercials. But, being at Screen Gems that day, brought back memories of eight successful years of “the business” in Atlanta, and thirteen in Los Angeles.

The director arrived. The casting agent apologized for him. The director did not apologize for himself. I was third in line to go in to read for him. When I walked in, the director was eating. I thought “damn, he’s an hour late and he’s sitting in the audition eating a sandwich.”

The casting associate positioned himself behind the camera. He would read with me. We exchanged pleasantries and took off. I did what I’d prepared for but also went with the flow of the scene. I know Mike. I’ve known many Mikes over the years. He was not a hard guy to inhabit. It felt good. I had the room. But then the director gave me the kiss of death. He turned to the casting associate and said, “All of them are so good.” I knew I was dead in the water. He didn’t need to blow smoke up my dress and make me feel good if he was going to hire me. It was Charles’ job. We all knew it.

I thanked them and met Gordon and Charles in the parking lot. Tony split. Alonzo having gone first was long gone. The three of us laughed and talked for another hour. We all vowed to get together but we knew the next time would probably also be an audition. The skyline of Atlanta loomed in the background. It felt good to hang out with the guys, where I began my career. Soon, it was time for me to hit the road. Other business interests outside of “the business,” beckoned. I gave the guys a hug and drove out of Atlanta.

By the way my phone didn’t ring.

I always wanted to write a tribute to my Dad. I knew I would at some point. Like most tributes it would be after he had passed away and his life would be big parts of my memory. He died at ninety-six. He had no debilitating illness, or disease. He couldn’t hear primarily because he refused to wear his hearing aid. He stopped enjoying life. He outlived everyone around him but his three offspring. He lost his wife 21 years ago after they had been married 49 years.

I am a part of his legacy and proud to be so.

He grew up in Elmore County, Alabama with his eleven brothers and sisters. Wetumpka, Alabama was the town that

served as the city center. Yeah, it was rural.

He told me tales of him and his brother Acon as teens plowing behind a mule from sun up to sundown for fifty cents a day. On the Fourth of July he told me they would get a watermelon and go down to the creek. Put the watermelon in the cold water and swim until exhausted, then eat the melon for their fourth of July celebration. He and his brother built themselves a bicycle from old worn pieces of different bikes. They would ride into town, and go to the movies, of course, sitting in the upstairs colored section. He liked school but because they were share croppers he would be pulled from school to work the fields.

At eighteen, he joined the Army. Afterward, he, his brothers and sisters migrated to Birmingham pursuing the city’s

good paying jobs in the steel plants. They would live with their older sister until they found jobs and moved out. Daddy and Acon married sisters. Daddy started work at Acipco Pipe and Foundry. He was there for the next thirty-five years. I don’t recall him ever missing a day. “You don’t work. They don’t pay you,” he planted into my brain.

When I turned nine years old, he and my Mom moved us to Rosalind Heights, a small community of new homes built for working class blacks near the Birmingham Airport. “The Heights” as we who lived there called it was a great place to grow up. My friends from the Heights are still my friends. The men from that era got into their work cars every morning and headed to their respective jobs to make their mortgage and feed their families.

The wives and mothers made our lives complete. They made our houses, homes, full of love and discipline, and hope for the future.

My parents and the community sent me off into the world of integration. I was the representative. Everyday, my sisters and I caught two city buses to get to our Catholic School across

town.

My mom had gone to a Catholic school and church, her dad had helped to build. We were raised to know that being different was not a bad thing. We didn’t have to be like everyone else. We didn’t have what many others had but it was okay. Our parents were investing in our future. Daddy took on a part time job to pay our tuition.

At fourteen, my life in many material ways surpassed my dad’s. I was doing things he had never thought possible in his world. Yet, he was never jealous, envious, or tried to hold me back. As I entered worlds that were far different than the one he lived in, he took his hands off the wheel of my life and trusted that I had absorbed the lessons he had taught me regarding manhood, responsibility, and legacy. When I stumbled he didn’t do the “I told you so,” but rather he and my mom a formidable team would nudge me back on track, wanting me to have the best life I could have. They never stood in the way of my decisions, quitting my job in management at BellSouth to pursue my own business and act and write part time. It was not the safest route to a fulfilling life, but here I am and it’s a helluve ride thanks to them.

My favorite story of my Dad is “the snow story.” I’d reached adulthood, working at South Central Bell. There was a fierce snowstorm in Birmingham. Shut things down. Nearly impossible for people to get to work unless you worked an essential job to keeping the city running. I called my Mom and talked to her. I asked to speak to my Dad. Mom, replied, “He’s gone to work.” “Gone to work?” I asked. Their driveway was on an incline. Impossible to back out of with the snow and ice. “He left here at three this morning walking,” she responded. That evening in the afternoon paper, there was a photo of a man walking down a snowy railroad track in North Birmingham, walking toward Acipco. “You don’t work they don’t pay you.”

My Dad would tell me as recent as a few years ago that he regretted not having money to give me. He often felt he could have done more when my high school and college teammates would show up with new clothes and cars. I always responded, “You taught me how to be a good man. For that I am grateful.”

Daddy taught all of us, my brother n laws, nephews, grandchildren and my friends “how to be a good man.” He taught my sisters and the women in the family what to expect from a good man.”

“Doc” Everybody in our family on both my Mom’s side and Daddy’s side called him Doc. No one we know living

knows why. It fit him.

As he told me on a couple of occasions, “Everybody I know is gone,” he said. He was lonely. At 96, Doc decided he

was tired and needed to rest alongside our mom, Catherine, the love of his life.

“We’re all just passing through,” he once told me. “We’re on our way to somewhere else.”

“When you come to the fork in the road, take it.” Yogi Berra, a thirteen time Major League Baseball World Series champion once gave this advice to a stranded friend seeking further direction to Yogi’s home. When the caller responded with, “huh?” Yogi repeated with a clear vision, “When you come to the fork in the road take it.”

Since Yogi spit those words of wisdom they have also been interpreted as coming to a crossroads in ones own future, a deciding moment in life when a major choice includes options. When faced with a choice, afraid of what is seen and unseen do you make the choice and venture down the road, confidant enough to face uncertainty?

Recently, two good friends of mine, the two Susans I call them, undecided on their respective futures, came to their personal fork in the road. Having lived responsible, accountable and accomplished adult lives they both knew it was time for a life change. They stood at their proverbial fork in the road.

Susan G. knew it was time when the business she had loved all her adult life no longer brought her that joy. She had risen from a receptionist in the business to one of two owners. She was in charge, made money and her colleagues were friends. But, the thrill was gone! Going through the daily motions her mind drifted. In her mid 50s, she wanted more, a new direction She took the fork.

After a trip to Key West and visits to friends across Florida, she’s still deciding what’s around the next bend. But the sun has never shined brighter. The days last longer. Her smile is bigger. The joy in her voice has returned. She’s happy.

Susan P. (yes, they’re both Susans) surprised me with her announcement. I heard of it from a client friend. The friend also relayed that Susan’s boss and colleagues who depended on her expertise were talking to her to see if she could be convinced to stay. They felt she would. A month went by before I ran into her. We talked. She opened up about the upcoming season of her life and how she was looking forward to what was next. I knew she was a goner, one foot out of the proverbial door.

She’d discovered the strength to do what had been floating around inside her for some time. She was heading back to her hometown to be close to relatives. She would seek part time work that she could control with companies she was already familiar with. They had already approached her. She would be a big fish in their tiny fish bowl. But, she would not be in charge of the entire operation as she had been. She could work like she pleased. She could spend time with her Mom. She met with the companies. She set the terms. They agreed to the letter “I can’t believe it,” she jubilantly expressed. She is happy.

Both women pondering a life move reached their fork in the road and made their choice without having all the answers.

They both individually asked me for my advice. “What do you think,” they wanted to know? Without hesitancy, I quoted Yogi, “When you come to the fork in the road, take it.” I remember the laughter. They both laughed big, hearty, throaty laughs. They’re laughing even louder now.

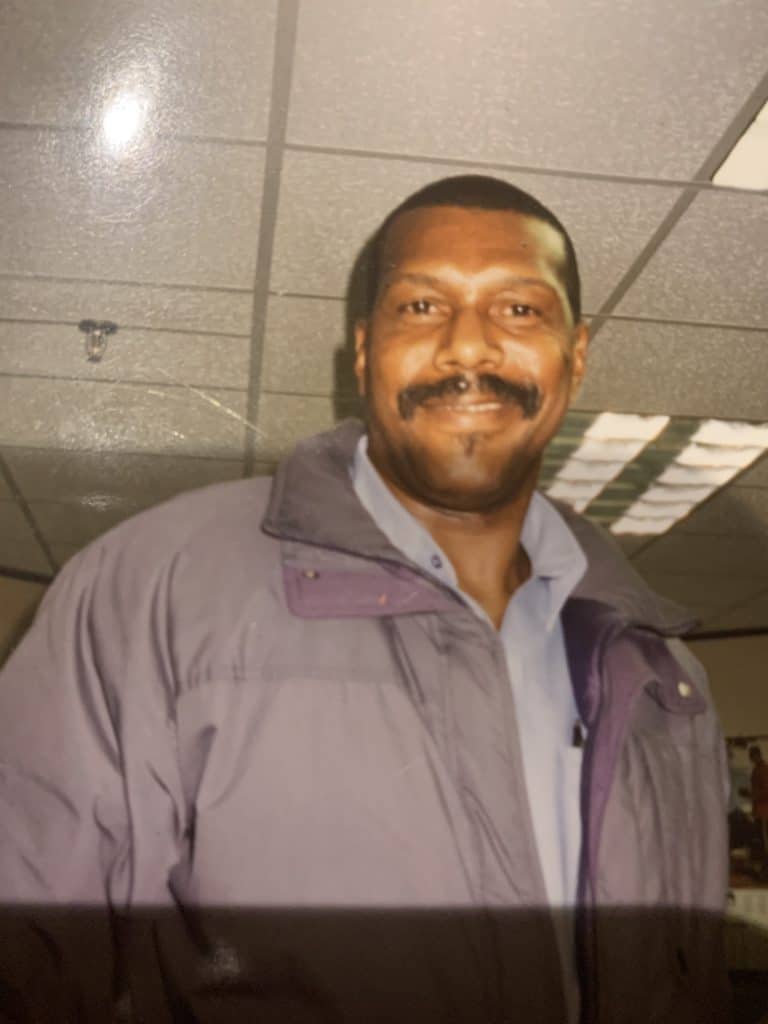

Big Emmett is gone! I don’t know any other way to say it. Big Emmett is gone. Big Emmett was my brother N law for the past 46 years. He passed away on Saturday January 30 from cancer.

The call came at 7:44 on Saturday evening. It was one of those phone calls that seemed odd for the time of day for whatever reason. When my phone started its familiar chime and I looked down to see my sisters name I knew something was up. Initially I thought it might be something with my dad. He’s 95 and I’m always fearful of getting that call in the middle of the night about him.

It was my younger sister. Her voice had a gravity to it. Yep, something was up. Something was wrong! I waited. I waited while she worked around to getting to what she had called for. Before long she said Big Emmett had passed. DAMN! Damn was the word that spilled immediately from my mouth. I knew he was sick but… I would send him a weekly text to ask him how he was doing and his answer was always upbeat, instead asking how I was doing, how my family was? I let it sink in. Big Emmett is gone! He went peacefully with my older sister, the love of his life, by his side.

Emmett was stage four… But he was Big Emmett. My Dad is 95 and I could have reasonably expected the call to be about him. I have another brother-in-law with cancer as well. He’s been critically ill for a while. The call could have been about him. But not Big Emmett!

It will take some getting used to. I don’t know anybody who didn’t like him. I never heard anyone say anything bad about him. I’ve called a couple of people who knew him from college and his marriage to my sister. They have expressed the same surprise I did.

“Solid.” That was my dad’s description of him. “Solid.” Someone you could count on. Someone who gave comfort to others. After my Mom passed and my Dad started living alone. Emmett called him every morning. Every morning on his way to work Emmett would call my dad just to check on him. If Daddy didn’t answer for whatever reason, Emmett drove to his house. If I came into town to visit my Dad, Emmett always came over and he, daddy and I would have big laughs, about our lives, family.

Why was he called Big Emmett? It’s true he was a big man, six foot eight a former athlete, and he has a son named Little

Emmett. But that wasn’t why I called him Big Emmett. He wasn’t flashy, wealthy, a big shot, a celebrity. He was Big Emmett

because he was a big man in terms of being as my dad said, solid. Solid in terms of caring for others, in terms of caring for his family, in terms of caring for my dad like he was his dad, which Daddy became. He was always there whether to talk and laugh, check on Daddy, be a good father and grandfather, be a brother to me, a good husband.

I will miss him I’ll always love him. Big Emmett. Solid as a rock.

A pink piece of paper.

There are many things for me to be thankful for this Christmas Season. Most have to do with family and the joy and happiness you see on the faces of others. Some others come in the mail in bright colors and small envelopes. One came yesterday. The envelope is like any other. What’s inside is what makes me smile. It’s a pink 8.5”x11” Royalty Statement. Pink? Yes! Pink! Why Pink? I don’t know but it gets my attention as soon as I see it.

It’s amazing how that piece of pink paper can lift my spirits with its pleasant memories.

Is money in the envelope? Yes, that’s a part of the story. But just a part and not the part I’m smiling about. The amount of money is inconsequential. Matter of fact it’s generally not much. This time it’s a net $30.03. Not much to brag about. But like I said it’s not the money. It’s the memories!

I’ve been an active member of the Screen Actors Guild since 1983. It’s not a career I’d planned on. It happened. I’m glad it did. From community theatre on Birmingham’s Southside to the pink paper that travels across the ocean and finds me at home, it happened.

As an actor in the Screen Actors Guild we are paid residuals. Foreign payments are called Royalties. Many of the current foreign payments are from productions I was involved in during the 1980s, 90s and early 2000s.

Whenever I get one of these pink notices, about twice a year or so, I’m excited. Examining the pink paper, prompts me to look back over an unintended career. This payment is for some shows I’ve been in as far back as 23 years ago. But let me get to the point. What makes this thirty dollars so special is that it’s for foreign showings. Yep, this past quarter, I’ve been in shows and movies exhibited on television, streaming, and Internet services in the countries of Germany, Colombia, Portugal, Spain, and Switzerland. That makes me smile. I think it’s so cool.

The memories are priceless. Shooting from midnight to dawn outside for three weeks on Jeepers Creepers 2. The pink paper informs me that Jeepers ran in Spain. I remember flying to Los Angeles for the interview for Fight Club and flying back home for our son’s high school graduation. I got the call the next day telling me I had the job. When I remember the wrap party we had in Hollywood where I danced with Jennifer Anniston, a big smile creases my face. Fight Club ran in Spain and Switzerland. There’s the fun and friendship that still exists that I formed with my friend Joe Slowensky, the writer, on Miracle In The Woods. Miracle In The Woods ran in Germany.

I’ve been fortunate enough to travel abroad but I’ve never witnessed myself speaking in a foreign tongue in Colombia, Spain, Germany, or Switzerland. That would be cool. Maybe if I’m lucky I’ll get to see myself speaking in Spanish, French or German in a foreign Country. If not, I’ll continue to look forward to getting my pretty in pink memories.

A woman, victim of the California/Oregon wildfires, says she is moving. She’s adamant about it. “Out of the state,” she says. “Anywhere.” She can’t take the wildfires any longer. The blazes aren’t just devastating they’re deadly. In the recent fires fifteen people died and millions of acres burned. I get it! I’ve never lived near wild fires. On television they look to be awfully scary.

The weather is more threatening and menacing today than I remember growing up. The seasons themselves are confused. Summer used to reside in the summer months of June, July and August. Now it stretches itself into 6 months. Maybe September and October aren’t officially summer but the heat index says it is just as hot into late October.

So, can you really get away from it all?

Let me pose the question. You’ve decided to move somewhere in the United States. Somewhere safe from natural disasters. Where do you go? Whether it’s global warming or not, extreme weather is everywhere.

I grew up in Birmingham, Alabama. We had the occasional thunderstorm. Some bad enough where we would flee to the basement to get out of harm’s way. Now, deadly tornadoes whip through the Birmingham metro area, leaving devastation, death, power outages and temporary homelessness.

The same can be said for the plains areas of the country. In a news clip, two big monster tornadoes touched down in the same town at the same time; tossing deadly debris everywhere.

Of course there is always the Midwest, Chicago and the like. My wife grew up there. Did I mention winter’s below freezing blizzards and summer’s extreme heat??

I lived in Los Angeles for fifteen years. I moved there a few years after the big Northridge quake in ‘94. The damage was worse than a terrorist attack. My cousin would not go back into her home for 3-months fearing the delayed aftershocks. While living there, I would joke, saying that if I was in an earthquake and I lived, and if my car parked in the underground parking garage of the condo building was not damaged, I’d without any delay, drive across country to my home in Florida. I learned not to kid about it. Asleep one morning in my big solid Paul Bunyan four- poster bed, it started bouncing up and down. Had an automobile hit the building, I wondered? Nope! It was an earthquake. At least it was the aftershocks of one. Before I could jump out of bed and run to the doorway, as emergency management instructs, it was over. The bouncing bed calmed down. Scary? Weird? Different? Yes all of that. Turns out it was the aftershock of a

quake nearly 200 miles away. Wow!

On another occasion, while working at my desk in the upstairs office, the building shook, creaked, moaned and rocked. I recognized it right away this time. But again, before I could react, it was over. Again, it was aftershocks. Glad it wasn’t the real deal.

Which brings me to the Florida Gulf Coast and hurricane season. From June through November I’m a constant visitor to the National Hurricane site on my computer; watching the tropical waves spin off the African coast and into the ocean, hoping they don’t grow into monster hurricanes and come our way. As the babies become teenagers and journey across the ocean, I

read the constant updates from the Hurricane Center. Will it grow into a hurricane? A major one? Will it come our way? Will they name it? Who cares? Are we prepared? We’re always prepared! You better be.

We’ve evacuated once. Took us six hours to drive what had been four hours. We’ve been hit, once. Hard! It was that bastard, Ivan, a true monster. Ivan roared through, flexing its muscle. When it left, it took a third of our backyard with it. Drug it back into the bay creating a ten-foot drop. Destroyed our dock and left us with stories we still talk about sixteen years later and permanent scars on our memory. Strangely, he didn’t damage the house. But we had to live with the butchered yard, the ten-foot drop and the missing deck for nearly a year. Laborers who do the repairs once a hurricane hits, have far more business than they can handle. They’ll

agree to take your job and if they show up within six-months you’re lucky. When hurricanes hit there are bigger fish to fry.

When we finally got the decking and sea wall repaired, within one-week Hurricane Daniel came blowing through. Luckily, he was a smaller category 2 hurricane and more of a blowhard. We watched television through it. Never lost power. The seawall held.

While writing this I sat through Hurricane Sally. Never ending rain, causing the water in the bay to rise to dangerous levels. The hard driving wind took several shingles off the roof. Just for fun, she destroyed the dock, and threw our boat around like it was a toy. I hardly recognized it afterward.

We’ll regroup. But back to the original point of this piece.

I’m not kidding when wondering where the lady is going to move. Does a safe spot exist? When she finds out, I hope she’ll let me know.

“NEVER” has finally arrived! Yay!!!

Daniel Snyder the owner of the Washington NFL team vowed he would “NEVER” change the team name of the Washington franchise. “NEVER,” he promised. Ever since I heard Mr. Snyder issue his “Never’ declaration I have not let the nickname of that team cross my lips, not once.

Even though my childhood football hero Bobby Mitchell played for them and worked in the front office until his death this year. I simply called them The Washington team in the NFL.

How could the name not be offensive? What if they had been the Washington Crackers, or the Washington Blackies. Would that have been offensive?

But the culture change taking place in the country is moving us past hollow words and promises and into action to continue to move the country past systemic racism.

Money, pressure, loss of sponsorships and culture change make things happen. In late June, DC politicians and business leaders announced the team could not build a new stadium within the district without a name change. In addition, FedEx, Nike and Pepsi were among the companies that reportedly received letters from shareholders asking that they no longer do business with the Washington team. That did the trick.

Let’s move forward. We know better. Cleveland and Atlanta the baseball teams know better. Florida State knows better. Things change when viewed under the lens of a new world. The past was not always blissful, especially when large groups of people were disenfranchised with little or no say-so as to how they were perceived and used as pawns by majority business entities to make money.

After I’d written this and turned it into “The Communicator” Emily Hedrick for posting, Washington made more headlines. At least 15 women who work or previously worked for the team has accused executives of sexual harassment from inappropriate conduct to butt grabbing,

The world is changing. The Washington team needs to change with it. It’s about time!

I remember “the talk.” The talk that black fathers gave and probably still give to their sons. It was time. I was probably getting close to driver’s license age and that meant I could venture further from the nest on my own. The talk was serious. No! It wasn’t the sex talk. We had that one too. It was like the sex itself. Quick and… well you know.

No, this talk was more serious. It was the survival talk. How to survive an incident with the Birmingham police or a gang of angry white people. What has stayed with me all these years, was his concern. There was a threat out there and there was nothing he could do about it but put pass down lessons I could call on when needed. “Keep your hands visible at all time. Do whatever they tell you. Don’t make any sudden moves. Call home as soon as you can.”

Fortunately, as a teen in the 1960s, in my hometown of Birmingham, Alabama, I steered clear of the police and angry white people. We lived in a nice little neighborhood near the Birmingham Airport. It was the kind of neighborhood where we, my friends and I, could hang out at night under the street light and talk and laugh until it was time to go into our respective homes. It was a great place to grow up.

We lived in the county and every now and then a sheriff’s deputy would roll through the neighborhood. If we saw him first, we ran. Got out of eyesight. We would meet back up when he was gone. I told that to my wife many years later (she grew up differently) and she immediately asked, “why?” I responded, “Because it was the police.” We weren’t doing anything wrong. It was just best to avoid an encounter if you could. On a couple of occasions when the officer drove up on us before we could run without looking suspicious, he’d stop and ask us what we were doing. Or tell us to get our hands out of our pockets. We would always comply. He was never mean. But we never felt like he was there “to protect and serve us.” It felt more like he was there to keep us in line.

Those feelings have stayed with me far into adulthood. I’ve had some encounters. I’ve kept my hands visible. I’ve responded “yes sir” and “no sir” to young men in uniform half my age. On one occasion, I sat in the front seat of the friendly police officer’s car on the Opp, Alabama bypass and explained how my wife’s Prius Hybrid I was driving ran on both gas and a battery and where he could get one. I had an officer flip the little safety thing on his holster and put his hand on his gun, as we faced each other about 15 yards apart on Interstate I-85 coming out of Montgomery about 2:30 one morning. We were both scared. I could tell he was scared of me although I did nothing to raise his fear. His fear made me afraid of him. I raised my hands like in a western and explained what I was doing, where I worked and a bunch of other unnecessary information.

I had two police officers, in an unmarked car, stop me for speeding (I was) heading into Atlanta. They were not in uniform and in an unmarked sports car. From their look they could have been undercover. I was driving a new white Mercedes. It stood out. I explained that I was an actor and that I was late for an audition. That obviously didn’t go over too well because they proceeded to have me get out of the car, search my car, going through the glove compartment, and under the seats. They made me open the trunk. Searched the trunk. When I asked what were they looking for, they ignored me and continued the search. They never threatened me but it was scary. I said, “I don’t have any weapons or drugs.” Later I asked, “How do I know you won’t plant some drugs in my car.” They didn’t respond, didn’t find anything, and got back into their vehicle and sped off. I took a deep breath, wondered what had just happened and continued on my journey. I made the audition.

Later in life I gave “the talk” to my teen son before he went out one night. Because this was 30 years later than my talk with my Dad, and the world had moderated somewhat, it was of less significance to him. His teen world was a more diverse one than mine had been. He assured me that he would not be doing anything wrong or get into any trouble. I replied, “It’s not you I’m worried about son.”

A month ago when the news broke that Ahmaud Arbery, a young black man, was gunned down vigilante style by two white men in Georgia who felt they had that right, my now adult son, living in Georgia, with his own family, called and expressed his concern for the temperament of the country and his own safety. He felt the need to be better able to protect himself and his family. We had to have another “talk.”

Exhausted, I wheeled the bicycle into the driveway of the condo complex. It had been a grueling, mind-clearing twenty- six mile Saturday morning ride along the bike trail near the beach. The morning school of dolphins, swimming near the shore, had put on a big-time show with a feeding frenzy on a school of fleeing, jumping smaller fish. The Santa Monica sun had climbed overhead, forecasting one of fall’s warmer days. Sweat poured over me. The ride had helped to clear some but not enough of the storm clouds in my mind.

I unlocked the gate to the bicycle storage area and gathered myself, still dreading the day ahead.

This October 31st was a double whammy for my wife and me. She had elected not to get out of the bed. The thought of a year ago today made her weak and nauseous. The ache that resided deep down inside of her had not yet subsided.

“Are you coming, honey?” I had asked.

“No,” came the short and curt answer from under the bed covers. I understood.

Two years ago, my mom died on October 31st. It had been a slow debilitating ten-month bout with that bastard cancer. Over time my mom was no longer my mom but the shell she had come packaged in. Our roles became reversed as time ticked away and I became the caregiver and caretaker for the woman who had done that for me all my life. October 31, Halloween, would never again be a day of tricks and treats.

Then it happened again.

One year ago, on October 31st we lost my wife’s mom, who had become my second mom. Again, to cancer and again on the same date. This one had been a six-month battle, ending one year exactly to the date of my mom’s passing. It had been a two-and-a-half-year ordeal of hospitals, medicine, doctors, and finally a double loss.

The ride was designed to help me get through the day. Exhaustion would slow down my mind; suppress feelings, and bad memories. I didn’t want to spend the day feeling sorry for myself, even though, faith, the fuel needed to hope, no longer resided within me. My moms would tell me to move forward. I could only respond with “I’m trying.”

Then I saw Mary.

Mary, a petite, peaceful woman and our neighbor, was standing on the sidewalk in front of our building, crying. Slumped, she cried a silent cry. There were no wails, no moans, and no big demonstration. She was just standing there motionless with quiet tears flowing down her cheeks and off her face.

Mary, a foster mother, had given up her baby.

Mary stood on the passenger side of a big, black expensive SUV staring at the baby in the back seat. The lady who had come to take the baby away, a woman I didn’t know, stood in the street on the driver’s side of the vehicle. She was smartly dressed and reeking of class and dignity. The SUV, with the baby boy snugly and securely strapped in the back seat, separated the two women; two mothers in love with the same child.

Saturday morning dog walkers caught up in their own little worlds of dog walking, cell phone talking, and poop-cleaning, passed the two women and the baby boy. They did not see the drama unfolding in the eyes and hearts of the two mothers. Bike riders on their thousand dollar bikes, in their loud colored, spandex bike riding suits, whizzed by on the street, on their way to bragging about how far they’d ridden that day.

No one noticed.

The two women’s eyes never left each other’s. Mary had been here before; there was always some sadness when it was time to give up one of her babies. Being a temporary mom takes a special ilk. But this time was different. Mary had fallen in love with the baby boy.

How could you not?

He was special in the way that loved babies are. He was loved and he knew it. He had big blue eyes that glistened in his mocha colored skin. Who wouldn’t want to take him home?

Mary’s latest child stole the hearts of everyone in our complex. Mary had other babies before, but this baby, with those eyes, and that smile, and his apparent self-awareness became my favorite-the condo’s favorite. He was our baby. He was with us almost ten months, and Mary would, on sunny days, bring him into the courtyard where he always drew a crowd. He fit our little community. He made us all feel better by helping us to forget our lives and fall in love with his.

A mother who he probably would never know had given him up at birth. Within days he had been placed with Mary until an adoptive parent showed up. October 31st was the day he would leave one mom for another.

The new mom, negotiating unfamiliar emotional territory but nevertheless feeling the unconditional love only a mom feels, made a heartfelt, earnest plea to Mary. “Call anytime you want to,” she said. “I mean it. Early in the morning, it doesn’t matter. Visit whenever you want.”

Mary nodded through her tears.

The two women did not take any steps closer to each other, keeping their respectful distance. They did not want to touch. They only wanted to share their individual spaces with the little boy who ga- ga’d and goo-goo’d and slobbered in the back seat, unaware of the significance of this day, now both to him and to me.

The new mom wanted to and tried to leave but could not. As much as she wanted to get on with being a mom and loving her new son, she could not bear to break another mom’s heart. She paced back and forth from the driver’s door. She reached for the handle, opened it and then couldn’t get in. She let the door close again, all the time her eyes were connecting to Mary’s, and Mary’s to hers.

Finally, the stares were no longer enough. With nothing more to say, she got into the big vehicle. The SUV with Mary’s baby rolled off down the street and into other lives. The dagger in Mary’s heart had been as cold and as deep as the one in my own heart two years ago today, and my wife’s a year ago.

I joined Mary on the sidewalk, giving her a big hug. We cried silent tears for motherhood and our own individual loss.

“I’ve had him longer than any of the others,” Mary told me. “This is the most difficult good-bye.”

”Goodbyes are hard,” I agreed.

“He’s going to a great family,” she managed, I held on to her for a while.

We broke up our pity party and headed to our respective condo’s. My wife was still in bed, drowning in the memory of her loss. My mind, awake and churning again, wouldn’t stop thinking of the baby boy. Born into adverse circumstance, he’d already gotten a lifetime of love from two mothers and I’m sure well wishes from a third in just his first ten months of life. I hoped the love would continue to flow for him.

I thought of the new mom, a warm, seemingly loving human being, who was empathic enough to temper her excitement for herself, her family and their new loved one with compassion for Mary’s loss as only a mother can do. My mind ran to Mary whose love was so strong, it allowed her to give the babies up so other mothers could love them as well, again as only a mother can do. I couldn’t get the baby boy with the big pretty eyes, wrapped and strapped in the back seat on October 31st, out of my mind. The baby boy had created a new October 31st memory for me. I thought, in ten months of life he’d already had three moms.

How lucky!

Self-quarantining can make one reflective.

Bobby Mitchell died. “Who,” You ask? Bobby Mitchell!

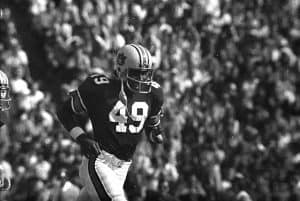

In the days of black and white television, Bobby Mitchell decked out in the uniform of the Washington NFL team and wearing number 49 on his back, captured my imagination and my heart. Bobby Mitchell was the first African American player to sign with Washington, the last team in the NFL to integrate. Bobby finished his NFL career with over 14,000 total yards, 91 career touchdowns, became an executive with the team and was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame.

In 1962, I was 11 years old and in love with football. That year, Bobby Mitchell was traded from the Cleveland Browns to Washington to complete what was then NFL integration. Washington’s owner had refused to add any blacks to his team, the only all white team remaining in the league. The Feds intervened. The pawn in the negotiations was Bobby Mitchell. But Bobby Mitchell was nobody’s pawn. He was a king who could do it all. He played halfback at Cleveland alongside Jim Brown, and receiver in Washington. On the sandlot fields of our neighborhood games, I was always Bobby Mitchell.

I also admired Bobby Mitchell the man. “Bobby,” says David Baker, the NFL Hall of Fame president and CEO, “was an incredible player, a talented executive and a real gentleman to everyone with whom he worked or competed against.”

Bobby became an ambassador, a scout, and an executive all for Washington. He was involved in civil rights; righting the wrongs he saw in society. He annually raised funds for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. As the player who would be the last piece of NFL integration he worked to positively represent Washington and the team. He didn’t get bitter. He kept doing the things he could do. He left that impression on me. Do the things you can do!

I chose Bobby’s number #49 for my three varsity seasons. I was always proud to wear number 49. I still am!