This Black History Month, I applaud Sam Heys a white man.

I became familiar with Sam Heys work when I read the book Big Bets, Decisions and Leaders that shaped Southern Company, about the founding and early days of The Southern Company, owners of Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia Power. Later, I would become familiar with Sam when he decided to write the story of Henry Harris’s integration of deep south collegiate athletics and I became one of his resources as he researched deeply into Henry’s life and his time at Auburn University. Henry was the first black athlete in the deep southern states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Florida, to sign a scholarship, and to play college sports when he signed with Auburn University in 1968.

I knew Henry Harris. Hung out with him, laughed with him, played cards with him, drank beer and played pickup basketball with him. Henry was my friend. He, and James Owens the first black scholarship football player at Auburn, were my big brothers. We lived in the athletic dormitory and helped to shepherd in southern college sports integration. Henry and I were two years apart. Reading Sam’s book about incidents and people I knew took me back, some who were courageous and others who hid behind traditions, court orders, the N word, and confederate flags.

As a former reporter for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, and The Columbus Enquirer, Sam asked and answered the two questions Henry, and most of the early pioneers, faced, “Do I want to have to worry about being physically or mentally harassed, or harmed or did I want to go to college and enjoy my college career?”

Sam asked these questions of Perry Wallace, the first black athlete in the SEC at Vanderbilt; Wendell Hudson, the first black athlete at The University of Alabama; and Nate Northington, at Kentucky; whose black roommate, Greg Page was killed in football practice.

I have often had to remind people that we were teenagers, leaving home for the first time. We were on the heels of Dr. Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement. It was less than a half dozen years after the signing of the Civil Rights Act. Laws had changed but people hadn’t. It was a tense time. Neither of us had any previous experience in our families with higher education. We were good at our sport and good enough citizens for the formerly all white universities, to take a chance on.

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama, had opportunities for a basketball scholarship at Villanova, who wanted him badly. The University of Alabama wanted him to be their “first.” Many other recruiters found the tiny town of Boligee and came calling. In today’s language, Henry was a five-star recruit. But, like many of the pioneers, he didn’t want to venture far from home and family. He represented a community, a group of people who wanted and needed integration in college sports to shine a bright light on past injustices and needed advancement in society. They wanted to make a difference.

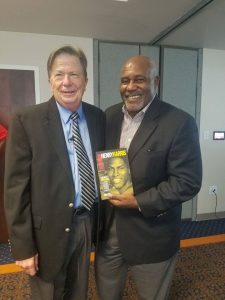

I bought the book in September. Sam was featured as a part of the Auburn 50th Commemoration of sports integration, a wonderful celebration during Black Alumni weekend with nearly 500 attendees. He brought his recently released book, Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution, A Story of Hope and Self Sacrifice in America. He familiarized many there with the story of Henry’s journey through Auburn.

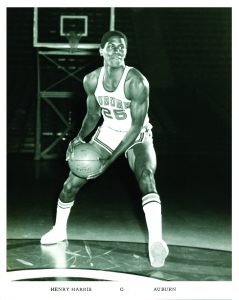

Sam writes, after the freedom rides, the bus boycotts, the sit-ins and the marches ended, Harris decided to make his life matter by going to Auburn University – the first African American on athletic scholarship at Auburn and, more importantly, the first black athlete at any SEC school in the Deep South. He was the seemingly quintessential candidate for integration, but nothing could have prepared him for the next four years. Fourteen years after Brown v. Board, he still had not sat in a classroom with a white person.

Knowing much of the story, I brought the book home and let it sit. Did I want to go back into what I consider to be dark days? It has always been difficult emotionally for me. I waited.

As we neared Black History Month, I picked the book up off my desk and let Sam take me back to those days once again. I read it in record time. I read it late at night and between 5 and 7 am, while my wife slept and the phone would not ring, knowing I would not be able to control the tears.

The book starts with depression, and an apparent suicide in 1974, when Henry was 24 and 2 years removed from his time at Auburn. As Sam reads an article from a newswire printer describing Henry’s suicide, he says the details were vague and the reporting was missing all the “whys.” Sam fills in the facts, answers the questions and traces Henry’s extraordinary odyssey, a passage that helped revolutionize the South and America.

A stranger in a strange land at Auburn, Henry learned early on the defense mechanisms needed as an integration pioneer. He learned, like all of us, to keep things bottled up inside. Keep your true feelings to yourself. Don’t let others know how you really feel so that you won’t be labeled an agitator, an ingrate.

Henry said all the right things, “What convinced me was the atmosphere at Auburn. Coach Lynn along with the other coaches and players were pleasant people to talk with and they made you feel like you were wanted.”

When asked how he wanted to be remembered, he responded, “As a basketball player who cares for other people.”

But an unhealthy restlessness boiled below the surface at the unfairness of it all. He played out of position. He played on a bum knee shot up with drugs to get through a game. He had to defer to others when he was the best player on the team. He had practically no social life. He never graduated.

There is a thin line between success, and happiness and “making it through.” For many of us, and in particular for Henry and James Owens, my big brothers, it would have been great to have the total college experience, but that was not the case. No effort was made by Auburn or any social organization to assimilate Henry into university life. For the most part of his four years he never had a roommate. Henry and James decided they just needed to make it through.

When he left the Auburn basketball court for the last time, he received a respectful 90 second ovation from the Auburn fans. He received a similar ovation at Kentucky where he had scored 43 points as a freshman. A Kentucky athlete who played against Henry said, “He was ahead of his day. He was a true gentleman.”

Sam says he was a hero. A hero supposedly suffers for those who follow him. Henry Harris was a hero. He gave himself to a cause bigger than himself. He played hard, he played hurt, and he kept his mouth shut. He knew what he had to do and he did it. He stayed – when all the stereotypes said he wouldn’t and common sense said he shouldn’t.

He made things better and possible for those coming behind him.

This Black History Month Sam Heys has given Henry Harris his justice. He has made others aware of Henry’s journey and his legacy. Henry deserves that and much, much more. Thank you Sam!

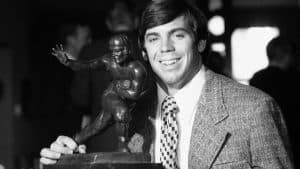

Pat Sullivan!

He was always nice to me and he didn’t have to be.

At John Carroll Catholic High School in 1966 in Birmingham, I was in 9th grade. He was in the 11th. He quarterbacked the football team, had a deadly corner shot in basketball that would easily qualify for today’s three pointers and… oh yeah he was outstanding in baseball.

On football Fridays, Pat and the other football players on varsity could come to school out of uniform, (white shirts, blue tie, charcoal gray pants) and wear their jerseys to class. They paraded like peacocks leading up to the afternoon pep rally and game that night.

On cool days they wore their letter jackets to school. They were cool, studs. Pat wore his with pride. I watched him. I studied him. He was special! Nice! I wanted to play with him. Pat would speak to me and give me a smile. That was important to me, more important than he knew. It was integration. I was a stranger in a strange land, navigating a new world, alone in a crowd. That smile meant and still means a lot.

Ultimately, I followed Pat Sullivan to Auburn. There, he again was, “the man,” still without the swagger. Without the arrogance that can sometimes come with being “extra.” He had an incredible career. He won the Heisman Trophy. He gave Auburn fans mental highlights that still flash across the screen in their heads today. He was #7.

I walked on at Auburn. Played freshman ball and got the coaches attention. They asked Pat about me. Imagine, they asked the star player about this black kid who walked on. A kid no one knew. But Pat knew me. He knew me enough to say that I had gone to John Carroll and that I was a good student. Pat told them that everybody liked me and most importantly, I was fast. That spring, I got more than a fair share of repetitions. One day, the coaches put me in for a few plays with the first team offense against the first team defense. I’ll never forget it. It’s great as a young athlete to look up to someone and then actually get to play with him, even if it is “just practice.” It was much more than that to me.

Pat stepped into the huddle and said to the linemen, “Hold them out guys, this one is a touchdown.” THEN… he called my number. I still remember the jitters in my stomach as I jogged out to my position. Surveyed the defense. I got open on a deep post route. Pat let it go. It fell into my arms. I cradled it like a newborn. “Touchdown.” Just like he said. I’ve been a believer ever since.

After that spring, the athletic department awarded me a scholarship. I had a chance to actually play with Pat his senior season. Then the coaches decided to redshirt me. I wanted to play with him! Still, I dressed and traveled every game. What a treat for me! I got to watch Pat up close. In Knoxville, he led us from behind to win 10-9. We ran off the field like we had stolen something. We had a victory. At Georgia, he won the Heisman. What an afternoon. He was the field general, in command. The Auburn fans felt the electricity. His teammates felt it. They would run through walls for him. They believed in him. When Pat ran off the field I waited for him to trade hand slaps.

Other than that magical spring when he threw me the ball every chance he got, I never again played with Pat. But he made me feel like the closet teammate. Great people can make others feel as though their relationship is uniquely special. It’s one-on-one. I felt that way with Pat.

In 2007, I asked Pat if he would write the forward for my book, WalkOn My Reluctant Journey to Integration at Auburn University. He agreed. He wrote in part…

…I try to instill in our players some of the lessons I learned from those times, the journey of life and the foundation a young man can lay for his own future. I use Thom Gossom as an example of a man who had a dream, a vision of himself, that he never gave up against all odds,…

Thank you Pat Sullivan for nurturing that dream and helping to make me possible.

“Our history is our history.” The statement poured from my mouth as I talked to one of my good friends, an Auburn University alumnus about Auburn University athletic integration pioneers, Henry Harris and James Owens. “Who,” you may ask, as you were not around then, or your memory doesn’t extend back that far.

Let me school you.

First of all, recalling history can sometimes be difficult, especially for those who chose to be on the wrong side of that history. We should never run away from our history. When we do, we can very well repeat it. Maybe in another form or fashion, but we can repeat it. We should also never try to rewrite our history to make it fit the circumstances that make us more comfortable. In loving an institution, such as Auburn, which I do, it is imperative for me to also be objective about it. Our history is our history.

I am not a historian. However, I know what I have lived. I know what I witnessed. I know what I saw others go through. I know how those days of early sports integration made me feel. It’s now been fifty years. Auburn University will honor the feats of these two men with a commemoration during the University’s Annual Black Alumni Weekend.

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama was the brave soul who entered first.

Henry broke the color barrier of sports integration at Auburn University in the fall of 1968. It was four years after Auburn University desegregated, due to a court order, by accepting their first and only black student at the time, Harold Franklin. He left three months later.

According to Sam Heys author of Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution: A Story of Hope and Self-Sacrifice in America. Henry was not only the first black athlete at Auburn he was also the first black basketball or football player on scholarship at any of the, then seven, SEC colleges in the Deep South.

Heys writes that Henry’s signing was more than a college sports issue. “Historically it is important to remember that the integration of college sports was as much a civil rights issue as it was an athletic issue. College sports were the final citadel of segregation in the Deep South. Within a year of Auburn making the first move by signing Harris, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi State all integrated their football or basketball programs. LSU and Ole Miss followed within two years of Harris coming to Auburn.”

James Owens, from Fairfield, Alabama, walked through the door of sports integration at Auburn next. His chosen sport, football, cast an even brighter spotlight on his integration effort. James often confided to me, that without Henry, he would have left. James said, “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I thought it would be about playing football where I had excelled all my life but this was more than that. I had to be more than a football player. Everything I did was monitored and watched. I was a hero to the blacks. I was a mystery to the whites.”

In 1968, Auburn essentially became the leader in moving toward equality and justice in the Deep South. Sam Heys writes, “Auburn should be proud of the leadership position it took in signing Henry Harris to a basketball scholarship.” Does that mean that Auburn did everything right? NO! There were plenty of rough patches. It does however highlight Auburn’s willingness to step forward before any of their brethren. It also means Henry and James were willing to take that step along with the University. The University, Henry and James became willing leaders in this great cultural experiment.

Did these men have great careers? On the field they were good. They were leaders, not superstars.

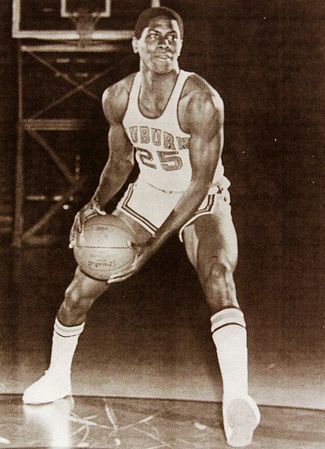

Statistically, Henry averaged 12 points 7 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game. He made third team All-SEC after the ‘71-‘72 season.

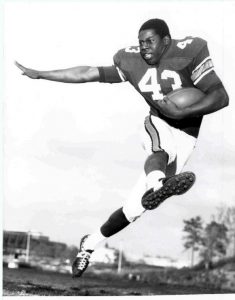

In the ‘71 and ‘72 seasons, James averaged 5.1 yards from scrimmage, 29 yards on kick returns, 10 yards on pass receptions and 4.1 yards rushing. Not bad considering the few times he got his hands on the ball.

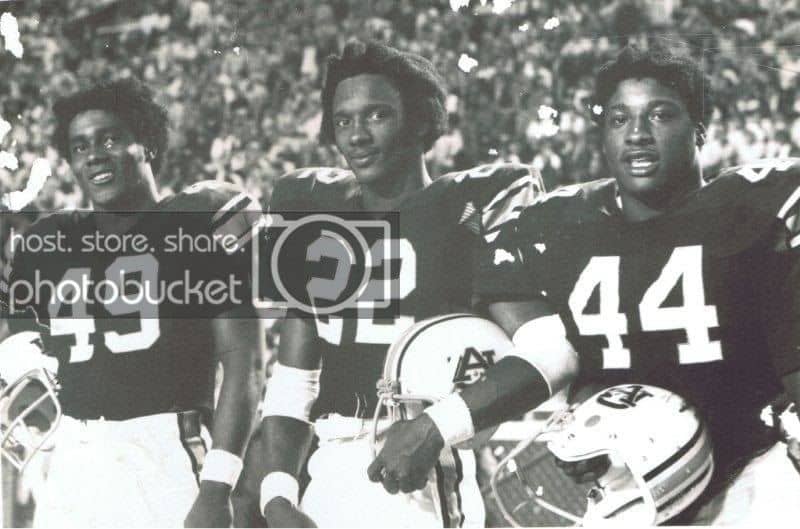

But far more important than their statistics, they led the way. They led their teams and inspired others, including me. They represented the University well. They sacrificed for others. They opened the floodgates. Personally, they became my big brothers when I joined them at Auburn in 1970.

I witnessed their feats on the basketball court and the football field. I also witnessed their hardships, their loneliness, their courage and their despair. While I was at Auburn, Henry never had a roommate. James and I lived together his last year.

These men may never be in any Sports Hall of Fame. They should be! Does changing a segregated way of life compare with running a touchdown or grabbing a rebound? Are you kidding? Is there any comparison? I know my answer. They may never be included with the outstanding athletes whose names are carved in cement on the streets of downtown Auburn or whose busts are included in the SEC Hall of Fame. But they belong there. Plain and simple, they belong there.

Fourth and goal, the crowd was frenetic! The constant roar of the two hundred thousand historic fans measured at jet airliner decibels. It was a moment as big as any in modern history. The ball sat squarely on the two-yard line going in. The clock sat still at :03. The Reb defense, tired and gallant, dug in to protect its turf. The Rebs led 21-17. The world was watching. Everything hung in the balance.

It had been a long time coming!

. . . . .

It began in 2008, with the election of Barack Obama as President of the United States. Obama’s presidency was filled with vitriolic racism channeled through talk shows and entertainment news. It was all about political and economic gain, but with the country in a recession, it was easier to cast doubt on a man of color and what his aims were. “Muslim,” they had called him. In the last years of his presidency, violence flared up along the unspoken boundary between North and South.

It had actually begun decades earlier with the deregulation of the media. Fewer interests controlled most of the airwaves. Independent voices disappeared. News outlets needed to fill the day-long, twenty-four hour news cycle with features, talk and, of course, lots of advertising. Bobbing head commentators subbed for serious news.

The division of red and blue states was not far behind. Next came rancor, resistance, little congressional cooperation, and a government run by corporate interests.

The people? The people were mired in ignorance, led there by bought and paid for leaders.

Under President Jeb Bush, the divisions grew deeper and more pronounced. A chasm developed in the country, fueled by politicians needing to be re-elected. Jeb promised he wouldn’t be a worse president than his brother, “W.” He was. Bush’s directives, cronyism and the reversal of President Obama’s course sent the country back to the fearful, duct tape, shop till you drop, Osama Bin Laden, be fearful of those different from you, the terrorists are coming to get you days. Jeb infuriated the liberals. But something new happened. The liberals fought back. No one had counted on that happening. The liberals had never fought back before. But, flushed from their safe havens of intellectualism, the once staid liberals did something beside talk. “An eye for an eye,” became their war cry.

President Duvall Patrick, after much deliberation and counsel with his War Chiefs, decided that short of war, there was only one way to settle things. Elections? They no longer mattered. In 2025, no one believed in or trusted elections anymore. Elections could be bought or decided by a Supreme Court ruling. The controversial Supreme Court Ruling of 2010 allowing an endless supply of cash to flow into elections meant not only that elections could be bought, but also recalls could reverse elections, as with the short lived tenure of President Hillary Clinton. Neither of the three political parties was able to get a sixty-vote majority in the Senate. Things ground to a halt in Washington D.C.

The settlement was the one thing the southern republicans, the tea party people, the young, the gay, the independents, the helpless, the rich and the liberals could agree on.

During his 2025 State of the Union address, President Patrick announced the plan for a World College Super Duper Bowl I. Every four years, beginning in 2025, the country’s political differences would be settled by a football game.

The nation celebrated.

. . . . .

The North called timeout. Yank quarterback, Abdul Lewis, “the traitor” as the Southerners called him, because of his Alabama heritage, jogged over to meet his coach, the legendary Paul D. Jones.

Southern linebacker Co-Captains, Leroy Gilliam, and Kassan Lewis, Abdul’s younger brother, jogged over to their equally legendary head coach, Jake Snead from Ole Miss.

The bands on either side of the field broke into their respective fight songs. The Yank band played The Star Spangled Banner. The Reb band broke out a rousing version of Dixie. The 200,000 fans on both sides of the specially constructed stadium that sat geographically right in the middle of the country’s Mason–Dixon line, stood yelling and screaming, some with hands over their hearts, other drunk off their ass.

I never intended to become a Hollywood actor. Maybe I thought about it in my youth but growing up in Birmingham, Alabama in the 1960s, made Hollywood seem like a distant world.

As children, my sister Donna and I performed on a variety show at Immaculata High School. We did some dance. Variety shows were big deals. Kids from throughout the neighborhood and the school participated. But that was it until high school and Miss Hilda Horn, my speech teacher, had me do a walk across the stage near the end of a school play. I wanted a part in the play and she wanted me in the play, but I was playing football.

I did readers’ theatre in college with Dr. Overstreet. It was fun. Again, football limited my time.

After college, I made a new discovery, one that would feed my soul, community theatre. Not just any community theatre, this was theatre at a very high level. The only professional thing we didn’t do was get paid. Still, I loved it. Working in management at BellSouth/AT&T, I’d shuck my suit every evening and head to the theatre for a rehearsal.

I was back working on a team goal.

There’s a feeling I’d get before playing a college football game. I describe it as an inner intensity that allowed me to run faster, jump higher and never get tired. Theatre rekindled that for me. Backstage, before the show, you hear that audience buzz, the sound of anticipation. It is a major high. Fences, Master Harold and The Boys, I’m Not Rappaport, American Buffalo, Ali were all highlights.

So how did I get to Hollywood?

I was discovered (ha!ha!) doing community theatre in Birmingham, Alabama at the tender age of 31, ancient for a beginning actor. Shirley Crumbley, a casting director, called one morning after the previous evening’s performance. Shirley said the director Milton Bagby was doing a film in town. He had been at the performance the night before and wanted to write me into his film. I said yes! That was it, simple and easy. I did the part. Met some people I still know today and went back to my job.

Before long, with the connection of an Atlanta Agent, I went before Carroll O’Connor to read for the part of the city councilman in the television series, In The Heat Of The Night. I won the part. We shot the show in Covington Georgia. For the next six years, in a recurring role I played Ted Marcus. I learned Television. Plus, I got to keep my job and live at home!

After that series wrapped after 6 years, Miss Ever’s Boys and Big Ben Washington came calling. Miss Ever’s Boys for HBO shot all over the Atlanta area. I was Big Ben! It was a high level production with Hollywood stars at the top of their game, Alfre Woodard, Lawrence Fishburne, and director Joe Sargent. It is a great piece of work.

So how did I get to Hollywood? I’m getting there….

joyce, my wife and I attended the Miss Ever’s Boys premier in Los Angeles. We love premieres. They are big parties with a lot of dress up fun. You dress up. You stroll down the red carpet. People take your picture. Everybody is beautiful. Heeeyyy!

After the film, we feasted on good food, and acting compliments. Then… Todd stepped into the picture and altered our lives. Two weeks later, I was in Los Angeles with Todd as my agent.

I was in and out of Hollywood for the next 13 years. It was a great run, NYPD Blue, Fight Club, ER, Boston Legal, Jeepers Creepers 2, commercials, and theatre. I worked up and down California. After 13 years, Hollywood followed me back to the South. It moved to Atlanta and all over the Southeast. I’m back with my original agent. I do my auditions in my office, e-mail them to my agents and they put me in front of the decisions makers. Oh yeah, I still feel that quiet intensity.

So, that’s it. That’s how I got to Hollywood… and back!

The simple question sent my mind reeling backward through time to those hot, hot, muggy oppressive days of summer. The question was from a neighbor commenting on how hot and uncomfortable the month of July has been. Temperatures have resided in the mid 90s with the heat index well into the 100s.

Ours is a walking, jogging, bike riding neighborhood. People stand in the yard and talk to each other. These days you can do that early morning and late evening but during the middle of the day the heat has been too much. My neighbors question sent my mind back to the heat of yesteryear.

“How did you all stand practicing outdoors in this hot sun? I can’t imagine,” was the question?

I answered immediately, “I don’t know. Sometime I ask myself that question.”

Looking back to the 1970s, it was always brutally hot in Auburn, Alabama in July and August. For clarification, it’s brutally hot in Auburn most summers. But for that five-year period, I was practicing with the football team in the steamy hot sun, with no breeze and only the occasional water break.

Walking on, I had to prove I deserved a scholarship. I did. I had to earn a starters job. I did. I had to keep that job for three years and help us win games and national rankings. I did that too. Standing in the hot sun with my neighbor, I felt a trickle of sweat run across my brow and down my face. Looking back on it now, in a six-decade old body, I wonder how we did it as well.

You see it was about more than being a big man on campus, the glamour of television, or signing autographs. Those were the byproducts, the benefits of hard, grueling, day-to-day grinding work in summer camp. Since school had not started we could devote all our time to practice. Summer camp could make or break our season.

We were young and frisky like colts. Reporting to camp we went at it twice a day for two full weeks before we tapered off to a regular practice schedule. The heat was unbearable. But we were on a mission. We went out in the morning in full pads. We hit, we hit and we hit some more.

In the afternoon practice we did it all over again. Dripping wet with sweat, our pads and practice uniforms now weighed close to ten pounds more as they were soaked. There was no Gatorade. There were no water coolers. It was according to our coaches, “How bad do you want it?”

We did get the occasional water break! People laugh when I tell them we had a water spigot about six inches off the ground that we had to kneel down to slurp its precious cold water on our two water breaks a day. It was yesteryear when the hardship of making a football team was equated with your manhood. “Prove you’re a man,” was the message we were given. If that was what it took to be a man we were willing.

My mom feared for me because I could not hold my weight in that hot sun, running miles and miles a day. I assured her I was okay.

Between practices we stuffed ourselves with food. Caught a quick nap and headed back out for the afternoon practice. Before dressing out we would check the afternoon depth chart. Had anybody moved up on the roster? Had I moved up on the roster?

Inevitably we reached that point in practice where attrition would take hold and those who refused to do it any longer would pack their bags and ease out of their dorm room under the cover of darkness and sneak off to another life. Putting that experience in their rear view mirror. We didn’t hold it against them. Maybe it took more courage to leave than it did to stay.

Was it worth it? Yes! Would I do it again? Yes! Absolutely. Could I do it again at this stage? Absolutely not!

As I explained to my neighbor what that part of my life was like, I smiled as I remembered the angry screams from coaches, the camaraderie we built, the games we won, “the teammates for life” tag we have placed on ourselves. The stories we now tell. All because of that “torture” we underwent in that brutal oppressive heat.

“I don’t see how you all did it,” my neighbor exclaimed.

With youthful exuberance and a big smile, the words shot from my mouth, “It was fun.”

“I’ll go first,” Buck instructed. “Then Chris, come in. Tyrone, you hang around outside near the door. Don’t cause no suspicion now. Got it?” Buck, from the drivers’ seat, stared at Tyrone in the rear view mirror.

Chris, from the passenger seat, waited for Tyrone’s answer. Tyrone nodded but without conviction.

Quiet and darkness set in inside the car as Buck settled the Blue Camaro onto the exit ramp of the freeway. They began their descent into the city.

Tyrone’s full stomach felt queasy. Buck had insisted they eat on the way to the job. He stopped at Church’s Chicken® on Martin Luther King Boulevard, got a family box of greasy chicken, dinner rolls, corn on the cob, and ate it in the parking lot of the fast food restaurant. Tyrone ate a wing and couldn’t eat anymore. He had no appetite.

Buck devoured the drumsticks, breasts, two ears of corn, two dinner rolls, sucked down a 24 oz. strawberry soda, and belched a sinful, nasty, loud, vulgar belch then said, “Let’s do this.”

They rolled toward the western side of town.

Anticipation gripped Tyrone in the darkness of the back seat. His chest was tight, his throat dry. His 6’1” frame hardly fit into the tight back seat of the sports car. He slumped and bent his head forward to find some comfort for his long legs.

Tyrone’s long legs had carried him to the 400-meter state finals in high school. “Little Horse,” they called him. He finished second, but no scholarship offers came his way. He had no money for further education.

I’ve been to this store many times before. The thought drifted across Tyrone’s brain. The car hit a bump in the worn road. The coldness of the blue steel in Tyrone’s pants touched his skin. This ride to the store was different. He knew it. He removed the gun from inside his pants and placed it on the seat, pointing it away from himself and toward Buck

Tyrone had tried to get his old high school buddy Goose to come along. He’d begged Goose, but Goose begged off. “Ain’t going to jail, Jack,” Goose responded.

Approaching the destination, Tyrone could see the blinking lights of the 7-11®. The city streets were naked, with the exception of an old, fat bag lady wobbling her way home from the bus stop and a day of scrubbing, cleaning, and caring for someone else’s home and children. She walked as though her feet hurt, and her next step would be her last. A step, a wobble; she would shift her weight then take another step, another wobble. Tyrone thought, Everyone has to make a living.

Buck had instructed that they all wear black windbreakers and a black cap just like he’d seen the bad guys do on CSI-NY, his favorite show. “Zip up,” Buck commanded.

Sweat beads gathered on Tyrone’s forehead. Even though it was a warm night, cold chills crept into his bones. Was this the dumbest thing he’d ever done? How could he get out of it? Was he scared of Buck? He was damn sure afraid of Chris. What about his family?

He’d married Pam two weeks ago. It felt good to marry the mama of his two-year-old son. He promised to get a job and help her with the bills. A good woman, Pam worked as a nurse. She was smart with money. She and Tyrone had dated since high school. She had gotten pregnant their senior year.

He thought of his son. Little Man, they called him. Tyrone had been so proud the day he was born. He’d held him so close, those first few days. He’d vowed to do right by his son. He tried. He drove cabs. He did day labor. He’d landed a career opportunity loading trucks with UPS®. Thirty days later, they fired Tyrone for a positive marijuana test. He hadn’t worked in a year. Desperate, he tried to make nice with his father long enough to get his rent covered. Daddy said, “No way. When I tried to help you, you didn’t want it.” His father had arranged a job for Tyrone in the steel plant where he’d worked for forty years, but Tyrone turned it down. “I ain’t working in no plant,” he emphatically told his father the last time they had talked.

Buck’s gruff voice interrupted Tyrone’s thoughts. “Get ready.” Buck, at nineteen, was a convicted felon and a violent veteran criminal. He slowed to make the right turn into the parking lot but then suddenly accelerated and passed his mark. No one said anything. Tyrone breathed a little easier. Both Tyrone and Chris had faith in Buck. Tyrone thought, Buck’s the man. He knows what he’s doing.

Buck circled the block, making sure there were no cops around. He came back and made his turn. The lot was vacant. The store was empty of customers. Chris reached over and killed the radio.

Buck pulled the Camaro next to the rectangular building with flashing neon lights. Only the old man was inside, just as Buck had figured and Tyrone had said. Tyrone hit the illuminating dial on the watch Pam had given him, 10:49. Buck turned, checked his piece of big, cold blue steel, and demanded, “Everybody be cool. It’ll be over in three minutes. Don’t be a fool.”

Buck opened the door, slid from under the wheel, and made his way around the car. He shoved the gun into the back of his pants just like criminals did on television. Chris followed. He shoved his gun down into the back of his pants, just like Buck. Tyrone lingered for a few precious seconds. He’d begun to sweat and beads of water trickled down his forehead, into his eyes. He thought about running. Just running. Maybe, running track again. When he was running track, it had been the happiest time of his life.

“Damn,” he murmured.

The night air was thick, the heat a forewarning of trouble. Water beaded up on Tyrone’s forehead and ran from under his arms. Like Buck and Chris, Tyrone tucked the gun into the back of his pants.

He started for the door about the time he figured Buck and Chris were inside. Tyrone was the lookout. He was afraid, afraid to go through with it and afraid to leave.

Tyrone could see the old man, Mr. Perkins. He knew Mr. Perkins through his grandfather, who also worked at this store. Tyrone had casually mentioned that his grandfather, his father’s father, worked at a 7-11®, and Buck had taken it from there. Tyrone had protested, but Buck reasoned it was all the way across town and their heads would be covered. No one would get hurt. He swore it would be a piece of cake. Tyrone stood his ground and insisted the job be done when his grandfather was not working.

Tyrone peeked inside the store. He did not want Mr. Perkins to see him.

Mr. Perkins had retired from his job in the factory. His wife had died five years before. He worked in the 7-11® to make a few bucks and get out of the house. Tyrone’s grandfather had recommended him to the owner, who hired him. Mr. Perkins stood slightly slumped and his hair grew in gray patches throughout his head. His customers loved him and his pleasant disposition. He, in turn, enjoyed his interaction with his customers.

Looking through the glass, Tyrone lost his focus. Mr. Perkins reminded him of his grandfather. He pictured his grandfather standing behind the counter with Buck and Chris in the store. What would he do?

Tyrone snapped out of it, made it to his position. Buck, Chris, and Mr. Perkins were the only ones in the store. Things were moving smoothly. No problems.

Mr. Perkins did not see him.

Suddenly, without warning, the old man’s eyes came alive, registering danger. He’d spotted the piece in the waistband of Chris’s pants as Chris bent over pretending to look for some Oreo cookies. In a split second, Mr. Perkins, a kind, lovable older man, went under the counter for his piece, a Charter Arms Undercover .38 special.

Instantly, Buck, a veteran crook and felon with no dreams and no future at nineteen years old, went for his automatic, shouting, “He got a gun.” Chris, having spent a few years in juvenile detention and having enthusiastically watched too many Criminal Minds episodes, dove spread eagle, behind the row of cookies.

Tyrone, paralyzed, watched it all unfold. He could not flee, nor could he help.

The old man fired the .38 special twice in Buck’s direction. Bam! Bam!

Buck, kneeling, gun pointed sideways like he’d seen in the new rap video, fired multiple rounds. Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop! Pop!

It was surreal to Tyrone. It looked like television. The images were so vivid! The old man shooting, Buck behind the potato chip counter, and Chris lying prone on the floor, firing like a marksman. Tyrone thought about his own gun. The thought made him sick.

This wasn’t television. It was for real. His nervous stomach threw up the Church’s Chicken® wing.

In the next instant, fate slammed the door on all four lives.

Buck rose, his gun sideways, and fired multiple times. The bullets caught Mr. Perkins full in the chest like target practice. Tyrone saw blood gush and squirt through the gray flannel work shirt. It wasn’t like television at all. It wasn’t surreal. It was real, bloody, and scary as hell. Bullets tore away at Mr. Perkins’ flesh. Little pieces of his body flew in different directions. Mr. Perkins screamed out with the pain, became limp, and fell against the cash register, violently bumping his head. He hit the floor, lifeless.

It was time to go.

Tyrone’s legs started moving. He pulled his gun, threw it toward the dumpster in the parking lot, and broke for the freeway. His stride was long and casual, but his heart and mind were frantic. He replayed the picture in his mind—Mr. Perkins’ flesh being ripped open by the penetrating bullets. He tried blocking it but the pictures kept coming.

Sweat poured in currents from his body.

Tyrone ran. Running felt good. Running restored order to his world. He could control running. He started to relax. Running, he was able to think.

He didn’t know if Mr. Perkins was dead or not. Yes he did. He knew Mr. Perkins was dead. Damn! He didn’t look back for Buck and Chris. He never had to see them again, and it would be okay. He would never do this again. This had been stupid. He thought of Pam and Little Man. He was running to them. I’m on my way honey. Hey, Little Man, Daddy is on his way home. His thoughts raced along with him. Maybe I’ll call Daddy and get the job in the plant, he thought. Oh God, I hope so.

Somehow he ran up the entrance ramp to the freeway. Cars whizzed by. The thought of thumbing a ride entered his mind and exited just as fast. He continued running; his long strides now growing shorter; his breaths coming in fevered pants. He was no longer in running shape.

He never looked back. He didn’t stop running. He never again wanted to stop running, never again.

Sirens whistled in the distance, and he knew cops must be on the scene. Never losing stride, he hit the watch dial, 11:00 pm. It was time for his grandfather’s shift to start. Was his grandfather there? Would he find out? Would his dad?

Tired, exhausted, and run out, he wanted to quit running. He couldn’t go anymore. He wanted to stop. He wanted to be in the little one bedroom apartment with Pam and Little Man. He wanted the three of them to cuddle up in the bed his father had given him. He wanted to be home. Gradually, he slowed. Cars zipped by. He didn’t look backward or to the side. He only wanted to look straight ahead. He stopped running. He didn’t see or hear the Camaro pull up behind him. He didn’t hear the horn blow. When he heard his name called, it startled him. He turned.

Buck pulled the Camaro next to him, and commanded, “Get in.”

She saw him before he saw her. The flash of adrenalin shooting through her body upset her equilibrium. Excitement pumped in her chest. Uncertainty crept through her mind. Should she?

Yes? No? Duck and hide?

The old woman, talking in her ear, droned on incessantly. “So Simone…

Blah! Blah! Blah!” The old lady continued. Simone was oblivious to the old woman’s words. Her eyes were glued to him.

It had been fifteen years, another life ago, but he was aging well. He was a little heavier. He had a slight limp. He had less hair. His hair was now the silver color that gives men distinction. Dressed smartly, his body language said he was still comfortable in his own skin. He was still cocky, but in a more mature, dignified manner.

At the bar, a glass of wine in his hand, his eyes canvassed the reception. No one he saw interested him.

She sank further down in her chair.

Should she confront him? Say hello? Accidentally bump into him? Or just leave. Maybe he’d never know she was there.

She’d anticipated this moment for over a month after she had seen his picture in the Festival Program. Still, seeing him in the flesh had set off her alarms. She never thought of him anymore. She figured she had doused those embers a long time ago, but apparently not.

Had he seen her picture in the program? It was a nice picture. One she’d had made for the occasion of the book festival. The photographer had done a good job of hiding her baby fat.

. . . . .

The Montgomery, Alabama sun turned orange.

There was maybe another thirty minutes of sunlight left in the day and she was on his mind. Two days before the festival Eric had been shocked to find her picture in the festival lineup. He’d not heard of her book, based on her family’s Alabama Civil Rights History. Nor had he heard of, from, or seen her in the fifteen years since he’d...

Fifteen years ago he’d ended their relationship. No, he hadn’t ended it, he’d simply quit calling, would not return her calls, and within months married another woman. Someone he thought he’d always loved.

That was the best excuse he could come up with for his behavior.

Their mutual friends had to choose sides. Her female friends said he’d screwed up badly. “A dog, a low down, stinking, rotten dog,” they called him.

He’d convinced himself he would not be embarrassed to see her. “If I can avoid it, I will,” he thought. “Should I apologize?” The conversation played on in his head. “What if she’s forgotten? What if she’s simply moved on, not wanting to revisit the ugly past?” That would be a relief. He’d feel less guilty. He decided he’d play it by ear.

Besides, he was a different man today. Happily married, but not to the woman he dropped her for. That ended up being a living hell. Today, his life was peaceful and full of bliss. In addition to loving his wife and son, he liked them. They were his friends. They were his backers. His work required him to be away from home for long stints and they hung in there with him.

He had almost not made it to the Festival.

A scheduling conflict had him in two places at the same time. The important, but boring university meeting had droned on all day when he decided to skip out on the dinner hosted by the University President, and drive the fifty miles to the Book Festival reception.

He enjoyed book festivals. His book was doing well. The attention, money, and increased sales pleased him.

He liked the book world. It was the entertainment business yes, but the main characters, the writers in their rumpled clothes and smart glasses underplayed their roles. Writers, unlike actors, didn’t strut around like peacocks, their “look at me” attitudes flashing their colors. Most of the writers he’d run into at least had something to say. There was an intelligentsia. At book festivals, there were people eager to explore ideas and discuss differences.

He started to wander around the dusty reception area. He watched the authors and benefactors mingle. She was on his mind.

Suzie, the forty-something volunteer chairman, came over with a red headed friend accompanying her. “Eric, thank you so much for coming,” she sang in her Alabama accent. She draped herself over him in what passed for a hug. He felt her press her pelvis up against him, the way women will do when their hug says more than hello. He politely hugged her back.

For Eric, this function was strictly business. Suzie could only help him by giving him a platform to sell more books. There was one personal issue he needed to attend to and he would avoid that one if he could.

Suzie’s husband, Sylvester, standing by as his

wife groped Eric, obviously did not care. Sylvester was verbally engaged with a

sloppy, fat writer who liked himself far more than was warranted. Sylvester and

Suzie had been married 25 years and over that time

Sylvester had trysts with both girlfriends and boyfriends.

Suzie introduced her friend, the red head. Eric shook her hand. He thought she was cute, “southern white girl, cute.” Marge, an author, had written a book about her native state of Mississippi, Mississippi Mud. It had gotten good reviews and Eric promised to read it. All smiles and giggles, she couldn’t wait to ask, “Do you know Morgan Freeman?”

“No,” Eric begged off, excused himself, and wandered away to enjoy the Alabama Book Festival.

. . . . .

Simone had come from Washington D.C. where she was now a federal judge appointed by President Barack Obama. She was on track to fulfill her life’s ambitions. Back then, fifteen years ago, as they lay in bed, she had confided to him that one day she hoped to be on the U.S. Supreme Court.

He had made the journey from California. Hollywood, to be exact, a fantasy world he’d escaped into after college. He’d been successful but after a while, become bored. Since he’d gotten married, “for real this time” is how he described it, coupled with the changes in the business, he’d found writing as his rescue. Thus, he’d written a memoir about his early days in Hollywood and the stars he had known. It had been a kiss and tell with juicy, salacious sexual details.

There had been no mention of Simone. He respected her too much.

They had met in his hometown of Birmingham. She was the hotshot lawyer out of Harvard, working at a local firm for the summer. He was in town visiting his family. One of his lawyer friends hooked them up.

It had been a long-distance courtship, a whirlwind. Dates became weekends in D.C, New York, Los Angeles, and Birmingham. Hollywood and lawyer types were their friends. It was a wonderful ride, until one day she had rushed home from her clerk job on the federal bench to call him. She fell asleep waiting for his return call. It never came. She called again the next day wondering if he was ill. He did not answer. She called again that evening and again the next day. He never returned her calls. She tried again a week later, and again two weeks after that.

She never heard from him again. She never saw him again, other than television and films, until now. She did hear from a colleague that he’d gotten married.

“Why couldn’t he at least tell me?” she wondered.

. . . . .

Simone decided she had to conquer her fears, meet them head-on. She purposely walked right into Eric’s sight line, making sure he saw her.

He saw her. He smiled.

She was not a flamboyant woman. She was dressed comfortably but professionally. She projected the sexiness that comes from being smart and assured in your chosen area of life.

His smile of recognition lifted her.

“I didn’t want you to think I was ducking you,” she said, her words fighting through a nervous smile.

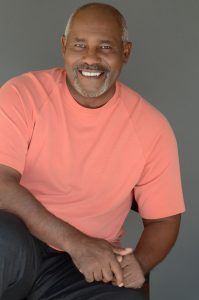

On January 21, 1952, at 7:30 pm at Holy Family Hospital in Birmingham, Alabama, I entered this world. My parents christened me Thomas Gossom Jr. after my dad. While that is my given name, over the years I’ve also been given other names. Some of these were out of fun; others are a play on my name. To me they all signify different episodes of my life.

Tommy is my childhood name. I was Tommy until I went to college. On the rare occasion these days when I hear “Tommy” directed at me, I know the person is from an earlier episode in my life. Those who still exist in Tommyland are comfortable there, perhaps a reflection of a more innocent time. I remember the cashmere jacket I had with “Tommy” written in script across the left chest area. It was cool! At least I thought so.

Radio is another one of my childhood names.This one was between my close growing up buddies and me. We all had nicknames. Cool, Bubba, Duck, Blood, and Radio were our handles. We were close then and still are today. I don’t remember how the nicknames came about. But I do remember the Radio was always on.

Possum Gossom was bestowed on me by my high school Coach Richard Porter. I think he came up with it because it rhymed with Gossom. Twenty years after high school, I was working on In The Heat Of The Night in Covington Ga. Having checked into my hotel I visited the gym next door. They had a track so I took a few laps. I recognized the man and woman walking in front of me. As I passed them, I turned and with a big grin greeted my coach, whom I had not seen in twenty years, “Coach Porter,” I grinned. He grinned, “Possum Gossom.”

Thomas wasmy name in high school and college as a football player and student. It has risen again, as I enter the fourth quarter of life.

Coach has followed mefrom being the B Team football coach at Parker High School until today with the guys I was lucky enough to coach. It was a special time for us. I am proud to have had that experience and those guys in my life. Occasionally in Birmingham, I’ll hear “Coach” directed toward me. Before turning around, I know it is one of my guys.

TG, G, The G weremy initial years. People dropped my name and called me by my initials. These years overlapped my college years and young adult years. TG became a nickname among my teammates. It still is with many. The G was an ego trip one of my friends laid on me. Yeah, I liked it.

Dark Gable is up there near the top of my list. When I started acting, and flying back and forth between my hometown and Los Angeles, the maintenance guys at The Birmingham Airport whom I had gotten to know, christened me “Dark Gable”. I would even wear my shades indoors for them as I headed to baggage claim. I loved the name then and now. Those guys gave a lot of love to Dark.

There were other names, some not so complimentary. Most of those were associated with my role in integration. White Boy was a name bestowed on me by some of the less enlightened in my black neighborhood. It was meant to be a slur on me as I went to private school with white students, and wore a white shirt, tie and blue or gray pants every day for twelve years. I grew to like being different.

Monkey, Baboon, Gorilla, The N word, and other disparaging words were thrown at me when I became a pioneer athlete in both the integration of my high school and college. I suppose it was an effort to discourage me from moving ahead in athletics, business and life. It didn’t work. The scars have healed. The memories rarely make me sad anymore. It was a time I was passing through on my way to now.

Thom came about as I began a television career as both a newscaster and an actor. The different spelling highlighted my name in the credits. It has stayed with me throughout my adult life.

I am still a hodgepodge of all my different years, names and episodes of my life.

When it’s all said and done, I’ll settle for Thomas Gossom Jr.

Chris McNair has died.

My first memory of him is of my being a little boy and greeting him as he brought the milk to our front door. A gregarious man, dressed in white and driving a White Dairy Milk Truck he was the milkman who my parents and aunts knew. Later, after I finished college and moved home to Birmingham, I went to work with him on his magazine, Down Home.

Down Home showcased his beautiful award-winning photography of people and places in the Deep South. I wrote many of the magazine’s articles both under my name and my pseudonym, Dwayne Stanley. We sold the magazine all over Alabama and to those black transplants who had generationally been a part of the great migration from the southern states to the good life, “up north.”

Working full time for BellSouth/AT&T, I would leave work, change clothes, get a bite to eat and spend the evenings at his studio, working with him on story ideas, accounting for the ads and magazines I had sold, and more importantly we would sit and talk. Because I had known him for so long, he always referred to me as “boy,” but that was okay. In terms of what I would learn from him, I was a boy.

Much has been written and discussed about him, the tragic death of his daughter in the

16th street Baptist Church bombing, his artistry as a photographer, his many civic and personal attributes, his time as a politician and his fall from grace. But for me it’s the nights we spent in his studio, talking, me mostly listening.

He often asked me about life at Auburn University where he would later send one of his daughters. He was interested in what life was like in the downtown corporate power structure, where I had “a good job.” I often detected regret at his having come along “too early,” to enjoy the rewards of integration.

Only once did I ever see him lower the barrier of his manhood and break down in tears as any man would who had experienced the life he had experienced, from Fordyce, Arkansas, to Tuskegee, to Birmingham, to the bombing at the sixteenth Street Baptist Church and the tragic loss of his daughter. “Why do we have to go through this?” he wailed, tears streaming down his face.

I didn’t say a word. It was his moment. I sat in silence.

I suppose I should say Chris McNair went to prison for stealing the people’s money. I’m a believer that you don’t run away from your history. He didn’t. He pled guilty to that crime. But if there was ever an elected official that the public wished could have been forgiven it was Chris McNair. He’d suffered enough many said. The crime and punishment was a testament to the contradictions of life. We can be upstanding in the light of day and perhaps do what we feel we need to do when the shadows of darkness surround us.

My memories will always be of the man I got to know personally and intimately, a man who during a five-year stint in my life became a mentor and friend. Toiling and talking in his junked-up studio, we strived to shine a light on what was happening “Down Home.”