“NEVER” has finally arrived! Yay!!!

Daniel Snyder the owner of the Washington NFL team vowed he would “NEVER” change the team name of the Washington franchise. “NEVER,” he promised. Ever since I heard Mr. Snyder issue his “Never’ declaration I have not let the nickname of that team cross my lips, not once.

Even though my childhood football hero Bobby Mitchell played for them and worked in the front office until his death this year. I simply called them The Washington team in the NFL.

How could the name not be offensive? What if they had been the Washington Crackers, or the Washington Blackies. Would that have been offensive?

But the culture change taking place in the country is moving us past hollow words and promises and into action to continue to move the country past systemic racism.

Money, pressure, loss of sponsorships and culture change make things happen. In late June, DC politicians and business leaders announced the team could not build a new stadium within the district without a name change. In addition, FedEx, Nike and Pepsi were among the companies that reportedly received letters from shareholders asking that they no longer do business with the Washington team. That did the trick.

Let’s move forward. We know better. Cleveland and Atlanta the baseball teams know better. Florida State knows better. Things change when viewed under the lens of a new world. The past was not always blissful, especially when large groups of people were disenfranchised with little or no say-so as to how they were perceived and used as pawns by majority business entities to make money.

After I’d written this and turned it into “The Communicator” Emily Hedrick for posting, Washington made more headlines. At least 15 women who work or previously worked for the team has accused executives of sexual harassment from inappropriate conduct to butt grabbing,

The world is changing. The Washington team needs to change with it. It’s about time!

I remember “the talk.” The talk that black fathers gave and probably still give to their sons. It was time. I was probably getting close to driver’s license age and that meant I could venture further from the nest on my own. The talk was serious. No! It wasn’t the sex talk. We had that one too. It was like the sex itself. Quick and… well you know.

No, this talk was more serious. It was the survival talk. How to survive an incident with the Birmingham police or a gang of angry white people. What has stayed with me all these years, was his concern. There was a threat out there and there was nothing he could do about it but put pass down lessons I could call on when needed. “Keep your hands visible at all time. Do whatever they tell you. Don’t make any sudden moves. Call home as soon as you can.”

Fortunately, as a teen in the 1960s, in my hometown of Birmingham, Alabama, I steered clear of the police and angry white people. We lived in a nice little neighborhood near the Birmingham Airport. It was the kind of neighborhood where we, my friends and I, could hang out at night under the street light and talk and laugh until it was time to go into our respective homes. It was a great place to grow up.

We lived in the county and every now and then a sheriff’s deputy would roll through the neighborhood. If we saw him first, we ran. Got out of eyesight. We would meet back up when he was gone. I told that to my wife many years later (she grew up differently) and she immediately asked, “why?” I responded, “Because it was the police.” We weren’t doing anything wrong. It was just best to avoid an encounter if you could. On a couple of occasions when the officer drove up on us before we could run without looking suspicious, he’d stop and ask us what we were doing. Or tell us to get our hands out of our pockets. We would always comply. He was never mean. But we never felt like he was there “to protect and serve us.” It felt more like he was there to keep us in line.

Those feelings have stayed with me far into adulthood. I’ve had some encounters. I’ve kept my hands visible. I’ve responded “yes sir” and “no sir” to young men in uniform half my age. On one occasion, I sat in the front seat of the friendly police officer’s car on the Opp, Alabama bypass and explained how my wife’s Prius Hybrid I was driving ran on both gas and a battery and where he could get one. I had an officer flip the little safety thing on his holster and put his hand on his gun, as we faced each other about 15 yards apart on Interstate I-85 coming out of Montgomery about 2:30 one morning. We were both scared. I could tell he was scared of me although I did nothing to raise his fear. His fear made me afraid of him. I raised my hands like in a western and explained what I was doing, where I worked and a bunch of other unnecessary information.

I had two police officers, in an unmarked car, stop me for speeding (I was) heading into Atlanta. They were not in uniform and in an unmarked sports car. From their look they could have been undercover. I was driving a new white Mercedes. It stood out. I explained that I was an actor and that I was late for an audition. That obviously didn’t go over too well because they proceeded to have me get out of the car, search my car, going through the glove compartment, and under the seats. They made me open the trunk. Searched the trunk. When I asked what were they looking for, they ignored me and continued the search. They never threatened me but it was scary. I said, “I don’t have any weapons or drugs.” Later I asked, “How do I know you won’t plant some drugs in my car.” They didn’t respond, didn’t find anything, and got back into their vehicle and sped off. I took a deep breath, wondered what had just happened and continued on my journey. I made the audition.

Later in life I gave “the talk” to my teen son before he went out one night. Because this was 30 years later than my talk with my Dad, and the world had moderated somewhat, it was of less significance to him. His teen world was a more diverse one than mine had been. He assured me that he would not be doing anything wrong or get into any trouble. I replied, “It’s not you I’m worried about son.”

A month ago when the news broke that Ahmaud Arbery, a young black man, was gunned down vigilante style by two white men in Georgia who felt they had that right, my now adult son, living in Georgia, with his own family, called and expressed his concern for the temperament of the country and his own safety. He felt the need to be better able to protect himself and his family. We had to have another “talk.”

Exhausted, I wheeled the bicycle into the driveway of the condo complex. It had been a grueling, mind-clearing twenty- six mile Saturday morning ride along the bike trail near the beach. The morning school of dolphins, swimming near the shore, had put on a big-time show with a feeding frenzy on a school of fleeing, jumping smaller fish. The Santa Monica sun had climbed overhead, forecasting one of fall’s warmer days. Sweat poured over me. The ride had helped to clear some but not enough of the storm clouds in my mind.

I unlocked the gate to the bicycle storage area and gathered myself, still dreading the day ahead.

This October 31st was a double whammy for my wife and me. She had elected not to get out of the bed. The thought of a year ago today made her weak and nauseous. The ache that resided deep down inside of her had not yet subsided.

“Are you coming, honey?” I had asked.

“No,” came the short and curt answer from under the bed covers. I understood.

Two years ago, my mom died on October 31st. It had been a slow debilitating ten-month bout with that bastard cancer. Over time my mom was no longer my mom but the shell she had come packaged in. Our roles became reversed as time ticked away and I became the caregiver and caretaker for the woman who had done that for me all my life. October 31, Halloween, would never again be a day of tricks and treats.

Then it happened again.

One year ago, on October 31st we lost my wife’s mom, who had become my second mom. Again, to cancer and again on the same date. This one had been a six-month battle, ending one year exactly to the date of my mom’s passing. It had been a two-and-a-half-year ordeal of hospitals, medicine, doctors, and finally a double loss.

The ride was designed to help me get through the day. Exhaustion would slow down my mind; suppress feelings, and bad memories. I didn’t want to spend the day feeling sorry for myself, even though, faith, the fuel needed to hope, no longer resided within me. My moms would tell me to move forward. I could only respond with “I’m trying.”

Then I saw Mary.

Mary, a petite, peaceful woman and our neighbor, was standing on the sidewalk in front of our building, crying. Slumped, she cried a silent cry. There were no wails, no moans, and no big demonstration. She was just standing there motionless with quiet tears flowing down her cheeks and off her face.

Mary, a foster mother, had given up her baby.

Mary stood on the passenger side of a big, black expensive SUV staring at the baby in the back seat. The lady who had come to take the baby away, a woman I didn’t know, stood in the street on the driver’s side of the vehicle. She was smartly dressed and reeking of class and dignity. The SUV, with the baby boy snugly and securely strapped in the back seat, separated the two women; two mothers in love with the same child.

Saturday morning dog walkers caught up in their own little worlds of dog walking, cell phone talking, and poop-cleaning, passed the two women and the baby boy. They did not see the drama unfolding in the eyes and hearts of the two mothers. Bike riders on their thousand dollar bikes, in their loud colored, spandex bike riding suits, whizzed by on the street, on their way to bragging about how far they’d ridden that day.

No one noticed.

The two women’s eyes never left each other’s. Mary had been here before; there was always some sadness when it was time to give up one of her babies. Being a temporary mom takes a special ilk. But this time was different. Mary had fallen in love with the baby boy.

How could you not?

He was special in the way that loved babies are. He was loved and he knew it. He had big blue eyes that glistened in his mocha colored skin. Who wouldn’t want to take him home?

Mary’s latest child stole the hearts of everyone in our complex. Mary had other babies before, but this baby, with those eyes, and that smile, and his apparent self-awareness became my favorite-the condo’s favorite. He was our baby. He was with us almost ten months, and Mary would, on sunny days, bring him into the courtyard where he always drew a crowd. He fit our little community. He made us all feel better by helping us to forget our lives and fall in love with his.

A mother who he probably would never know had given him up at birth. Within days he had been placed with Mary until an adoptive parent showed up. October 31st was the day he would leave one mom for another.

The new mom, negotiating unfamiliar emotional territory but nevertheless feeling the unconditional love only a mom feels, made a heartfelt, earnest plea to Mary. “Call anytime you want to,” she said. “I mean it. Early in the morning, it doesn’t matter. Visit whenever you want.”

Mary nodded through her tears.

The two women did not take any steps closer to each other, keeping their respectful distance. They did not want to touch. They only wanted to share their individual spaces with the little boy who ga- ga’d and goo-goo’d and slobbered in the back seat, unaware of the significance of this day, now both to him and to me.

The new mom wanted to and tried to leave but could not. As much as she wanted to get on with being a mom and loving her new son, she could not bear to break another mom’s heart. She paced back and forth from the driver’s door. She reached for the handle, opened it and then couldn’t get in. She let the door close again, all the time her eyes were connecting to Mary’s, and Mary’s to hers.

Finally, the stares were no longer enough. With nothing more to say, she got into the big vehicle. The SUV with Mary’s baby rolled off down the street and into other lives. The dagger in Mary’s heart had been as cold and as deep as the one in my own heart two years ago today, and my wife’s a year ago.

I joined Mary on the sidewalk, giving her a big hug. We cried silent tears for motherhood and our own individual loss.

“I’ve had him longer than any of the others,” Mary told me. “This is the most difficult good-bye.”

”Goodbyes are hard,” I agreed.

“He’s going to a great family,” she managed, I held on to her for a while.

We broke up our pity party and headed to our respective condo’s. My wife was still in bed, drowning in the memory of her loss. My mind, awake and churning again, wouldn’t stop thinking of the baby boy. Born into adverse circumstance, he’d already gotten a lifetime of love from two mothers and I’m sure well wishes from a third in just his first ten months of life. I hoped the love would continue to flow for him.

I thought of the new mom, a warm, seemingly loving human being, who was empathic enough to temper her excitement for herself, her family and their new loved one with compassion for Mary’s loss as only a mother can do. My mind ran to Mary whose love was so strong, it allowed her to give the babies up so other mothers could love them as well, again as only a mother can do. I couldn’t get the baby boy with the big pretty eyes, wrapped and strapped in the back seat on October 31st, out of my mind. The baby boy had created a new October 31st memory for me. I thought, in ten months of life he’d already had three moms.

How lucky!

Self-quarantining can make one reflective.

Bobby Mitchell died. “Who,” You ask? Bobby Mitchell!

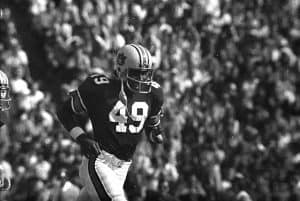

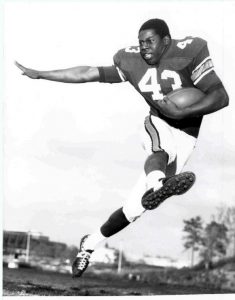

In the days of black and white television, Bobby Mitchell decked out in the uniform of the Washington NFL team and wearing number 49 on his back, captured my imagination and my heart. Bobby Mitchell was the first African American player to sign with Washington, the last team in the NFL to integrate. Bobby finished his NFL career with over 14,000 total yards, 91 career touchdowns, became an executive with the team and was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame.

In 1962, I was 11 years old and in love with football. That year, Bobby Mitchell was traded from the Cleveland Browns to Washington to complete what was then NFL integration. Washington’s owner had refused to add any blacks to his team, the only all white team remaining in the league. The Feds intervened. The pawn in the negotiations was Bobby Mitchell. But Bobby Mitchell was nobody’s pawn. He was a king who could do it all. He played halfback at Cleveland alongside Jim Brown, and receiver in Washington. On the sandlot fields of our neighborhood games, I was always Bobby Mitchell.

I also admired Bobby Mitchell the man. “Bobby,” says David Baker, the NFL Hall of Fame president and CEO, “was an incredible player, a talented executive and a real gentleman to everyone with whom he worked or competed against.”

Bobby became an ambassador, a scout, and an executive all for Washington. He was involved in civil rights; righting the wrongs he saw in society. He annually raised funds for the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. As the player who would be the last piece of NFL integration he worked to positively represent Washington and the team. He didn’t get bitter. He kept doing the things he could do. He left that impression on me. Do the things you can do!

I chose Bobby’s number #49 for my three varsity seasons. I was always proud to wear number 49. I still am!

This Black History Month, I applaud Sam Heys a white man.

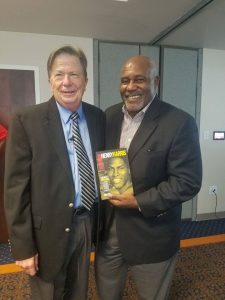

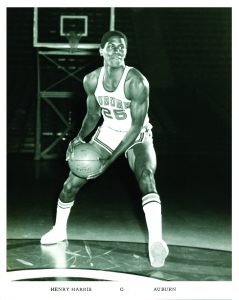

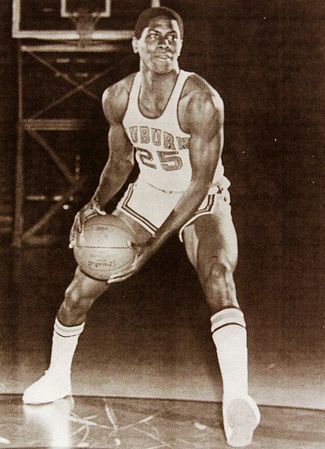

I became familiar with Sam Heys work when I read the book Big Bets, Decisions and Leaders that shaped Southern Company, about the founding and early days of The Southern Company, owners of Alabama, Mississippi and Georgia Power. Later, I would become familiar with Sam when he decided to write the story of Henry Harris’s integration of deep south collegiate athletics and I became one of his resources as he researched deeply into Henry’s life and his time at Auburn University. Henry was the first black athlete in the deep southern states of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana and Florida, to sign a scholarship, and to play college sports when he signed with Auburn University in 1968.

I knew Henry Harris. Hung out with him, laughed with him, played cards with him, drank beer and played pickup basketball with him. Henry was my friend. He, and James Owens the first black scholarship football player at Auburn, were my big brothers. We lived in the athletic dormitory and helped to shepherd in southern college sports integration. Henry and I were two years apart. Reading Sam’s book about incidents and people I knew took me back, some who were courageous and others who hid behind traditions, court orders, the N word, and confederate flags.

As a former reporter for the Atlanta Journal Constitution, and The Columbus Enquirer, Sam asked and answered the two questions Henry, and most of the early pioneers, faced, “Do I want to have to worry about being physically or mentally harassed, or harmed or did I want to go to college and enjoy my college career?”

Sam asked these questions of Perry Wallace, the first black athlete in the SEC at Vanderbilt; Wendell Hudson, the first black athlete at The University of Alabama; and Nate Northington, at Kentucky; whose black roommate, Greg Page was killed in football practice.

I have often had to remind people that we were teenagers, leaving home for the first time. We were on the heels of Dr. Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement. It was less than a half dozen years after the signing of the Civil Rights Act. Laws had changed but people hadn’t. It was a tense time. Neither of us had any previous experience in our families with higher education. We were good at our sport and good enough citizens for the formerly all white universities, to take a chance on.

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama, had opportunities for a basketball scholarship at Villanova, who wanted him badly. The University of Alabama wanted him to be their “first.” Many other recruiters found the tiny town of Boligee and came calling. In today’s language, Henry was a five-star recruit. But, like many of the pioneers, he didn’t want to venture far from home and family. He represented a community, a group of people who wanted and needed integration in college sports to shine a bright light on past injustices and needed advancement in society. They wanted to make a difference.

I bought the book in September. Sam was featured as a part of the Auburn 50th Commemoration of sports integration, a wonderful celebration during Black Alumni weekend with nearly 500 attendees. He brought his recently released book, Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution, A Story of Hope and Self Sacrifice in America. He familiarized many there with the story of Henry’s journey through Auburn.

Sam writes, after the freedom rides, the bus boycotts, the sit-ins and the marches ended, Harris decided to make his life matter by going to Auburn University – the first African American on athletic scholarship at Auburn and, more importantly, the first black athlete at any SEC school in the Deep South. He was the seemingly quintessential candidate for integration, but nothing could have prepared him for the next four years. Fourteen years after Brown v. Board, he still had not sat in a classroom with a white person.

Knowing much of the story, I brought the book home and let it sit. Did I want to go back into what I consider to be dark days? It has always been difficult emotionally for me. I waited.

As we neared Black History Month, I picked the book up off my desk and let Sam take me back to those days once again. I read it in record time. I read it late at night and between 5 and 7 am, while my wife slept and the phone would not ring, knowing I would not be able to control the tears.

The book starts with depression, and an apparent suicide in 1974, when Henry was 24 and 2 years removed from his time at Auburn. As Sam reads an article from a newswire printer describing Henry’s suicide, he says the details were vague and the reporting was missing all the “whys.” Sam fills in the facts, answers the questions and traces Henry’s extraordinary odyssey, a passage that helped revolutionize the South and America.

A stranger in a strange land at Auburn, Henry learned early on the defense mechanisms needed as an integration pioneer. He learned, like all of us, to keep things bottled up inside. Keep your true feelings to yourself. Don’t let others know how you really feel so that you won’t be labeled an agitator, an ingrate.

Henry said all the right things, “What convinced me was the atmosphere at Auburn. Coach Lynn along with the other coaches and players were pleasant people to talk with and they made you feel like you were wanted.”

When asked how he wanted to be remembered, he responded, “As a basketball player who cares for other people.”

But an unhealthy restlessness boiled below the surface at the unfairness of it all. He played out of position. He played on a bum knee shot up with drugs to get through a game. He had to defer to others when he was the best player on the team. He had practically no social life. He never graduated.

There is a thin line between success, and happiness and “making it through.” For many of us, and in particular for Henry and James Owens, my big brothers, it would have been great to have the total college experience, but that was not the case. No effort was made by Auburn or any social organization to assimilate Henry into university life. For the most part of his four years he never had a roommate. Henry and James decided they just needed to make it through.

When he left the Auburn basketball court for the last time, he received a respectful 90 second ovation from the Auburn fans. He received a similar ovation at Kentucky where he had scored 43 points as a freshman. A Kentucky athlete who played against Henry said, “He was ahead of his day. He was a true gentleman.”

Sam says he was a hero. A hero supposedly suffers for those who follow him. Henry Harris was a hero. He gave himself to a cause bigger than himself. He played hard, he played hurt, and he kept his mouth shut. He knew what he had to do and he did it. He stayed – when all the stereotypes said he wouldn’t and common sense said he shouldn’t.

He made things better and possible for those coming behind him.

This Black History Month Sam Heys has given Henry Harris his justice. He has made others aware of Henry’s journey and his legacy. Henry deserves that and much, much more. Thank you Sam!

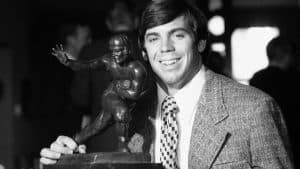

Pat Sullivan!

He was always nice to me and he didn’t have to be.

At John Carroll Catholic High School in 1966 in Birmingham, I was in 9th grade. He was in the 11th. He quarterbacked the football team, had a deadly corner shot in basketball that would easily qualify for today’s three pointers and… oh yeah he was outstanding in baseball.

On football Fridays, Pat and the other football players on varsity could come to school out of uniform, (white shirts, blue tie, charcoal gray pants) and wear their jerseys to class. They paraded like peacocks leading up to the afternoon pep rally and game that night.

On cool days they wore their letter jackets to school. They were cool, studs. Pat wore his with pride. I watched him. I studied him. He was special! Nice! I wanted to play with him. Pat would speak to me and give me a smile. That was important to me, more important than he knew. It was integration. I was a stranger in a strange land, navigating a new world, alone in a crowd. That smile meant and still means a lot.

Ultimately, I followed Pat Sullivan to Auburn. There, he again was, “the man,” still without the swagger. Without the arrogance that can sometimes come with being “extra.” He had an incredible career. He won the Heisman Trophy. He gave Auburn fans mental highlights that still flash across the screen in their heads today. He was #7.

I walked on at Auburn. Played freshman ball and got the coaches attention. They asked Pat about me. Imagine, they asked the star player about this black kid who walked on. A kid no one knew. But Pat knew me. He knew me enough to say that I had gone to John Carroll and that I was a good student. Pat told them that everybody liked me and most importantly, I was fast. That spring, I got more than a fair share of repetitions. One day, the coaches put me in for a few plays with the first team offense against the first team defense. I’ll never forget it. It’s great as a young athlete to look up to someone and then actually get to play with him, even if it is “just practice.” It was much more than that to me.

Pat stepped into the huddle and said to the linemen, “Hold them out guys, this one is a touchdown.” THEN… he called my number. I still remember the jitters in my stomach as I jogged out to my position. Surveyed the defense. I got open on a deep post route. Pat let it go. It fell into my arms. I cradled it like a newborn. “Touchdown.” Just like he said. I’ve been a believer ever since.

After that spring, the athletic department awarded me a scholarship. I had a chance to actually play with Pat his senior season. Then the coaches decided to redshirt me. I wanted to play with him! Still, I dressed and traveled every game. What a treat for me! I got to watch Pat up close. In Knoxville, he led us from behind to win 10-9. We ran off the field like we had stolen something. We had a victory. At Georgia, he won the Heisman. What an afternoon. He was the field general, in command. The Auburn fans felt the electricity. His teammates felt it. They would run through walls for him. They believed in him. When Pat ran off the field I waited for him to trade hand slaps.

Other than that magical spring when he threw me the ball every chance he got, I never again played with Pat. But he made me feel like the closet teammate. Great people can make others feel as though their relationship is uniquely special. It’s one-on-one. I felt that way with Pat.

In 2007, I asked Pat if he would write the forward for my book, WalkOn My Reluctant Journey to Integration at Auburn University. He agreed. He wrote in part…

…I try to instill in our players some of the lessons I learned from those times, the journey of life and the foundation a young man can lay for his own future. I use Thom Gossom as an example of a man who had a dream, a vision of himself, that he never gave up against all odds,…

Thank you Pat Sullivan for nurturing that dream and helping to make me possible.

“Our history is our history.” The statement poured from my mouth as I talked to one of my good friends, an Auburn University alumnus about Auburn University athletic integration pioneers, Henry Harris and James Owens. “Who,” you may ask, as you were not around then, or your memory doesn’t extend back that far.

Let me school you.

First of all, recalling history can sometimes be difficult, especially for those who chose to be on the wrong side of that history. We should never run away from our history. When we do, we can very well repeat it. Maybe in another form or fashion, but we can repeat it. We should also never try to rewrite our history to make it fit the circumstances that make us more comfortable. In loving an institution, such as Auburn, which I do, it is imperative for me to also be objective about it. Our history is our history.

I am not a historian. However, I know what I have lived. I know what I witnessed. I know what I saw others go through. I know how those days of early sports integration made me feel. It’s now been fifty years. Auburn University will honor the feats of these two men with a commemoration during the University’s Annual Black Alumni Weekend.

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama was the brave soul who entered first.

Henry broke the color barrier of sports integration at Auburn University in the fall of 1968. It was four years after Auburn University desegregated, due to a court order, by accepting their first and only black student at the time, Harold Franklin. He left three months later.

According to Sam Heys author of Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution: A Story of Hope and Self-Sacrifice in America. Henry was not only the first black athlete at Auburn he was also the first black basketball or football player on scholarship at any of the, then seven, SEC colleges in the Deep South.

Heys writes that Henry’s signing was more than a college sports issue. “Historically it is important to remember that the integration of college sports was as much a civil rights issue as it was an athletic issue. College sports were the final citadel of segregation in the Deep South. Within a year of Auburn making the first move by signing Harris, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi State all integrated their football or basketball programs. LSU and Ole Miss followed within two years of Harris coming to Auburn.”

James Owens, from Fairfield, Alabama, walked through the door of sports integration at Auburn next. His chosen sport, football, cast an even brighter spotlight on his integration effort. James often confided to me, that without Henry, he would have left. James said, “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I thought it would be about playing football where I had excelled all my life but this was more than that. I had to be more than a football player. Everything I did was monitored and watched. I was a hero to the blacks. I was a mystery to the whites.”

In 1968, Auburn essentially became the leader in moving toward equality and justice in the Deep South. Sam Heys writes, “Auburn should be proud of the leadership position it took in signing Henry Harris to a basketball scholarship.” Does that mean that Auburn did everything right? NO! There were plenty of rough patches. It does however highlight Auburn’s willingness to step forward before any of their brethren. It also means Henry and James were willing to take that step along with the University. The University, Henry and James became willing leaders in this great cultural experiment.

Did these men have great careers? On the field they were good. They were leaders, not superstars.

Statistically, Henry averaged 12 points 7 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game. He made third team All-SEC after the ‘71-‘72 season.

In the ‘71 and ‘72 seasons, James averaged 5.1 yards from scrimmage, 29 yards on kick returns, 10 yards on pass receptions and 4.1 yards rushing. Not bad considering the few times he got his hands on the ball.

But far more important than their statistics, they led the way. They led their teams and inspired others, including me. They represented the University well. They sacrificed for others. They opened the floodgates. Personally, they became my big brothers when I joined them at Auburn in 1970.

I witnessed their feats on the basketball court and the football field. I also witnessed their hardships, their loneliness, their courage and their despair. While I was at Auburn, Henry never had a roommate. James and I lived together his last year.

These men may never be in any Sports Hall of Fame. They should be! Does changing a segregated way of life compare with running a touchdown or grabbing a rebound? Are you kidding? Is there any comparison? I know my answer. They may never be included with the outstanding athletes whose names are carved in cement on the streets of downtown Auburn or whose busts are included in the SEC Hall of Fame. But they belong there. Plain and simple, they belong there.

Fourth and goal, the crowd was frenetic! The constant roar of the two hundred thousand historic fans measured at jet airliner decibels. It was a moment as big as any in modern history. The ball sat squarely on the two-yard line going in. The clock sat still at :03. The Reb defense, tired and gallant, dug in to protect its turf. The Rebs led 21-17. The world was watching. Everything hung in the balance.

It had been a long time coming!

. . . . .

It began in 2008, with the election of Barack Obama as President of the United States. Obama’s presidency was filled with vitriolic racism channeled through talk shows and entertainment news. It was all about political and economic gain, but with the country in a recession, it was easier to cast doubt on a man of color and what his aims were. “Muslim,” they had called him. In the last years of his presidency, violence flared up along the unspoken boundary between North and South.

It had actually begun decades earlier with the deregulation of the media. Fewer interests controlled most of the airwaves. Independent voices disappeared. News outlets needed to fill the day-long, twenty-four hour news cycle with features, talk and, of course, lots of advertising. Bobbing head commentators subbed for serious news.

The division of red and blue states was not far behind. Next came rancor, resistance, little congressional cooperation, and a government run by corporate interests.

The people? The people were mired in ignorance, led there by bought and paid for leaders.

Under President Jeb Bush, the divisions grew deeper and more pronounced. A chasm developed in the country, fueled by politicians needing to be re-elected. Jeb promised he wouldn’t be a worse president than his brother, “W.” He was. Bush’s directives, cronyism and the reversal of President Obama’s course sent the country back to the fearful, duct tape, shop till you drop, Osama Bin Laden, be fearful of those different from you, the terrorists are coming to get you days. Jeb infuriated the liberals. But something new happened. The liberals fought back. No one had counted on that happening. The liberals had never fought back before. But, flushed from their safe havens of intellectualism, the once staid liberals did something beside talk. “An eye for an eye,” became their war cry.

President Duvall Patrick, after much deliberation and counsel with his War Chiefs, decided that short of war, there was only one way to settle things. Elections? They no longer mattered. In 2025, no one believed in or trusted elections anymore. Elections could be bought or decided by a Supreme Court ruling. The controversial Supreme Court Ruling of 2010 allowing an endless supply of cash to flow into elections meant not only that elections could be bought, but also recalls could reverse elections, as with the short lived tenure of President Hillary Clinton. Neither of the three political parties was able to get a sixty-vote majority in the Senate. Things ground to a halt in Washington D.C.

The settlement was the one thing the southern republicans, the tea party people, the young, the gay, the independents, the helpless, the rich and the liberals could agree on.

During his 2025 State of the Union address, President Patrick announced the plan for a World College Super Duper Bowl I. Every four years, beginning in 2025, the country’s political differences would be settled by a football game.

The nation celebrated.

. . . . .

The North called timeout. Yank quarterback, Abdul Lewis, “the traitor” as the Southerners called him, because of his Alabama heritage, jogged over to meet his coach, the legendary Paul D. Jones.

Southern linebacker Co-Captains, Leroy Gilliam, and Kassan Lewis, Abdul’s younger brother, jogged over to their equally legendary head coach, Jake Snead from Ole Miss.

The bands on either side of the field broke into their respective fight songs. The Yank band played The Star Spangled Banner. The Reb band broke out a rousing version of Dixie. The 200,000 fans on both sides of the specially constructed stadium that sat geographically right in the middle of the country’s Mason–Dixon line, stood yelling and screaming, some with hands over their hearts, other drunk off their ass.

I never intended to become a Hollywood actor. Maybe I thought about it in my youth but growing up in Birmingham, Alabama in the 1960s, made Hollywood seem like a distant world.

As children, my sister Donna and I performed on a variety show at Immaculata High School. We did some dance. Variety shows were big deals. Kids from throughout the neighborhood and the school participated. But that was it until high school and Miss Hilda Horn, my speech teacher, had me do a walk across the stage near the end of a school play. I wanted a part in the play and she wanted me in the play, but I was playing football.

I did readers’ theatre in college with Dr. Overstreet. It was fun. Again, football limited my time.

After college, I made a new discovery, one that would feed my soul, community theatre. Not just any community theatre, this was theatre at a very high level. The only professional thing we didn’t do was get paid. Still, I loved it. Working in management at BellSouth/AT&T, I’d shuck my suit every evening and head to the theatre for a rehearsal.

I was back working on a team goal.

There’s a feeling I’d get before playing a college football game. I describe it as an inner intensity that allowed me to run faster, jump higher and never get tired. Theatre rekindled that for me. Backstage, before the show, you hear that audience buzz, the sound of anticipation. It is a major high. Fences, Master Harold and The Boys, I’m Not Rappaport, American Buffalo, Ali were all highlights.

So how did I get to Hollywood?

I was discovered (ha!ha!) doing community theatre in Birmingham, Alabama at the tender age of 31, ancient for a beginning actor. Shirley Crumbley, a casting director, called one morning after the previous evening’s performance. Shirley said the director Milton Bagby was doing a film in town. He had been at the performance the night before and wanted to write me into his film. I said yes! That was it, simple and easy. I did the part. Met some people I still know today and went back to my job.

Before long, with the connection of an Atlanta Agent, I went before Carroll O’Connor to read for the part of the city councilman in the television series, In The Heat Of The Night. I won the part. We shot the show in Covington Georgia. For the next six years, in a recurring role I played Ted Marcus. I learned Television. Plus, I got to keep my job and live at home!

After that series wrapped after 6 years, Miss Ever’s Boys and Big Ben Washington came calling. Miss Ever’s Boys for HBO shot all over the Atlanta area. I was Big Ben! It was a high level production with Hollywood stars at the top of their game, Alfre Woodard, Lawrence Fishburne, and director Joe Sargent. It is a great piece of work.

So how did I get to Hollywood? I’m getting there….

joyce, my wife and I attended the Miss Ever’s Boys premier in Los Angeles. We love premieres. They are big parties with a lot of dress up fun. You dress up. You stroll down the red carpet. People take your picture. Everybody is beautiful. Heeeyyy!

After the film, we feasted on good food, and acting compliments. Then… Todd stepped into the picture and altered our lives. Two weeks later, I was in Los Angeles with Todd as my agent.

I was in and out of Hollywood for the next 13 years. It was a great run, NYPD Blue, Fight Club, ER, Boston Legal, Jeepers Creepers 2, commercials, and theatre. I worked up and down California. After 13 years, Hollywood followed me back to the South. It moved to Atlanta and all over the Southeast. I’m back with my original agent. I do my auditions in my office, e-mail them to my agents and they put me in front of the decisions makers. Oh yeah, I still feel that quiet intensity.

So, that’s it. That’s how I got to Hollywood… and back!

“Coordinating with clients, managing schedules, planning projects, and keeping everyone informed and prepared.”

Is this you? Send us your resume!

Overview:

Effectively initiate, facilitate, and complete internal and external management related to Best Gurl and Client projects and activities. Manage projects, document preparation, schedules, travel, and client interactions on behalf of Best Gurl to create and maintain positive relationships and generate revenue.

Interpersonal Skills:

Technical Skills:

Salary and Benefits:

Negotiable, working from home office with flexible scheduling