“Our history is our history.” The statement poured from my mouth as I talked to one of my good friends, an Auburn University alumnus about Auburn University athletic integration pioneers, Henry Harris and James Owens. “Who,” you may ask, as you were not around then, or your memory doesn’t extend back that far.

Let me school you.

First of all, recalling history can sometimes be difficult, especially for those who chose to be on the wrong side of that history. We should never run away from our history. When we do, we can very well repeat it. Maybe in another form or fashion, but we can repeat it. We should also never try to rewrite our history to make it fit the circumstances that make us more comfortable. In loving an institution, such as Auburn, which I do, it is imperative for me to also be objective about it. Our history is our history.

I am not a historian. However, I know what I have lived. I know what I witnessed. I know what I saw others go through. I know how those days of early sports integration made me feel. It’s now been fifty years. Auburn University will honor the feats of these two men with a commemoration during the University’s Annual Black Alumni Weekend.

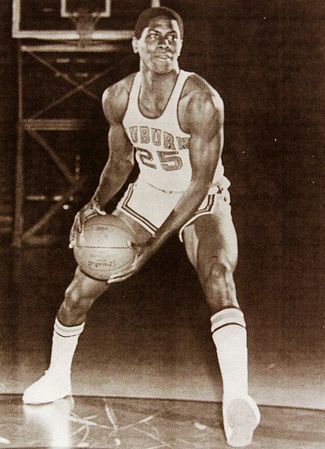

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama was the brave soul who entered first.

Henry broke the color barrier of sports integration at Auburn University in the fall of 1968. It was four years after Auburn University desegregated, due to a court order, by accepting their first and only black student at the time, Harold Franklin. He left three months later.

According to Sam Heys author of Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution: A Story of Hope and Self-Sacrifice in America. Henry was not only the first black athlete at Auburn he was also the first black basketball or football player on scholarship at any of the, then seven, SEC colleges in the Deep South.

Heys writes that Henry’s signing was more than a college sports issue. “Historically it is important to remember that the integration of college sports was as much a civil rights issue as it was an athletic issue. College sports were the final citadel of segregation in the Deep South. Within a year of Auburn making the first move by signing Harris, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi State all integrated their football or basketball programs. LSU and Ole Miss followed within two years of Harris coming to Auburn.”

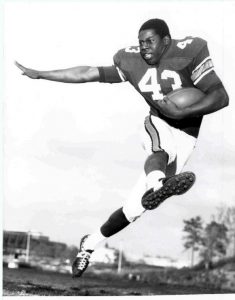

James Owens, from Fairfield, Alabama, walked through the door of sports integration at Auburn next. His chosen sport, football, cast an even brighter spotlight on his integration effort. James often confided to me, that without Henry, he would have left. James said, “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I thought it would be about playing football where I had excelled all my life but this was more than that. I had to be more than a football player. Everything I did was monitored and watched. I was a hero to the blacks. I was a mystery to the whites.”

In 1968, Auburn essentially became the leader in moving toward equality and justice in the Deep South. Sam Heys writes, “Auburn should be proud of the leadership position it took in signing Henry Harris to a basketball scholarship.” Does that mean that Auburn did everything right? NO! There were plenty of rough patches. It does however highlight Auburn’s willingness to step forward before any of their brethren. It also means Henry and James were willing to take that step along with the University. The University, Henry and James became willing leaders in this great cultural experiment.

Did these men have great careers? On the field they were good. They were leaders, not superstars.

Statistically, Henry averaged 12 points 7 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game. He made third team All-SEC after the ‘71-‘72 season.

In the ‘71 and ‘72 seasons, James averaged 5.1 yards from scrimmage, 29 yards on kick returns, 10 yards on pass receptions and 4.1 yards rushing. Not bad considering the few times he got his hands on the ball.

But far more important than their statistics, they led the way. They led their teams and inspired others, including me. They represented the University well. They sacrificed for others. They opened the floodgates. Personally, they became my big brothers when I joined them at Auburn in 1970.

I witnessed their feats on the basketball court and the football field. I also witnessed their hardships, their loneliness, their courage and their despair. While I was at Auburn, Henry never had a roommate. James and I lived together his last year.

These men may never be in any Sports Hall of Fame. They should be! Does changing a segregated way of life compare with running a touchdown or grabbing a rebound? Are you kidding? Is there any comparison? I know my answer. They may never be included with the outstanding athletes whose names are carved in cement on the streets of downtown Auburn or whose busts are included in the SEC Hall of Fame. But they belong there. Plain and simple, they belong there.

Alfre Woodward, the talented actress says to me, “I’ve got someone I want you to meet.”

“Okay,” I agreed.

She led me to a corner seat in the rented party room at the Santa Monica, California Airport. The party was for her husband’s birthday. The room was a who’s who of Hollywood stars having a good time outside the bright lights.

As soon as I saw the guy she wanted me to meet I told her, “I know this guy.” Of course I knew him. He was the secret service agent guarding the President every week on the hit TV show The West Wing.

But… there was something else. I actually knew this guy. He knew me as well. We excitedly shook hands. Alfre said, “I believe you are both from Alabama.”

That was true. He’s from Montgomery. I’m from Birmingham.

But, we’re more than that.

We immediately recognized each other because we’d both gone to Auburn University during the same time period. We had not been close friends, not even close acquaintances. We knew of each other the way you know of someone who has achieved some notoriety on a campus of 20,000 students. He had been involved in student government and his fraternity. I’d played football and written for the school paper.

It didn’t take us long to reacquaint. We soon got together for dinner with our wives and we’ve been fast friends ever since.

Michael O’Neill, “Michael O” I call him, is a professional actor. He knows his business. His IMDb page proves that. He has worked in more than 75 episodes of television and 30 films. Michael O has worked in New York, Los Angeles and across Canada. He’s worked with Alfre Woodard of course, Halley Berry, Martin Sheen, Clint Eastwood, Robert Duvall, and a host of others. Everyone except…

We often say between the two of us we have nearly 50-years of combined experience, more than 115 episodes of television and nearly 40 films. We have worked ER, Cold Case, Without A Trace, Boston Legal, Close To Home, The West Wing, NYPD Blue and Chicago Hope. But never had we worked together, until 2016.

Our Alma Mater, Auburn University, and the whole Auburn Nation was deeply involved in a $1 Billion Fundraising campaign. Michael O, I and others were asked to host, MC and dramatize a live 90 minute show in support of the campaign in Dallas, Houston, Tampa, Atlanta, Birmingham, Nashville, New York, and Washington D.C. We relished the opportunity to work together and to support our Alma Mater.

I caught up with him by phone for this post and it was like old times.

TG: Where are you?

Michael O: Working on a film in Memphis. Where are you?

TG: In Florida. I’m home for the next five days and then off again.

Michael O: Five days sounds like a vacation.

TG: Caught a break. I’m in and out the next three weeks.

TG: I have to ask you; we got to work together on the Auburn Campaign Events. What did it mean to you?

Michael O: It’s nice to give something back. It’s what you hope a college education can do. It reflects further than we could imagine. It’s easy to participate because I believe so strongly in the Performing Arts Center (coming to campus) and not just because you and I are in the arts but also because it’s important to our students and their interest, their outlook and their experience as they go out to shape the world.

TG: Talk about the night Alfre introduced us.

Michael O: That was funny! I remember my daughter Ella was 5-6 weeks old. It was the first time my wife, Mary and I had been out in a long time. We wanted to get out.

I had just worked on a project with Alfre, “The Gun in Betty Lou’s Handbag.” We had so much fun working together.

TG: She’s great. (TG worked with Ms. Woodard on Miss Evers’ Boys).

Michael O: That night in Santa Monica she told me, “I got somebody you got to meet.” She walked up with you and right away I said ‘I know him. We were in school together.’ I knew of you from campus, not just from playing football.

TG: That’s funny I told her the same thing. I know him. That turned out to be a special night.

Michael O: Yep.

TG: Talk about your current project.

Michael O: It’s set in Iraq. A young man goes off to war, gets thrown in the middle of everything and comes back with PTDS. He loses his faith and family. There is a very spiritual message to it. I play his mentor. Military guy.

TG:Do you get immersed in your characters? How far have your gone with this guy you’re playing?

Michael O: I’ve done so many films playing military guys and know quite a few guys. I consider it an honor. They help me with the research. I try to be very respectful. It has to be believable. I tell them, ‘don’t let me get caught acting.’

TG: Of all the projects you’ve done, what’s your favorite character and why?

Michael O: Mr. Pollard in“SeaBiscuit.”One of the first times I’ve wanted something so badly and got it. I blew it wide open in the audition. There were a lot of guys high above me in the food chain who were in line for that job, but they chose me in the audition. The character was actually written better in the film than in the book.

TG: I often like to say the profession is like being a migrant worker. Here today, on to the next gig tomorrow.

Michael O: I’ve worked in so many places. That’s been part of the cultural education. Off the top of my head let’s see what I can name. New York and Toronto several times, Based in LA, so all up and down California; Santa Fe, Salt Lake City, Atlanta, New Orleans, El Paso, all over Texas; Fort Davis Texas, Alpine Texas, Houston, and Austin. Umm, Lexington, Kentucky, Florida, London…

TG: I want you to tell me the Sully story; but first talk about being recognized on the street.

Michael O: (Laughter!) Will Geer (“The Walton’s” and “Jeremiah Johnson”) mentored me. He taught me that it’s more important to be interested in the other person rather than yourself. You have to want to give back to them. You’re sharing an experience with them. It feeds me as much as it does them. Whenever someone recognizes me on the street, my daughters(3) will always bring me back to earth. They roll their eyes at the fact I’m talking to someone I don’t know.

It’s always cool when we’re both together and someone recognizes the both of us.

TG:Yeah that’s always fun!

TG: Tell the Sully story.

Michael O: I’m riding down this elevatorand this guy is stealing glances at me. When the door opens before he gets out, he says, ‘You did a good job, landing that plane on the Hudson River.’ I responded, Thank you!

TG: Any of your girls following in your footsteps?

Michael O: Nope: They’ll find their own way.

TG: What advice do you give to those who ask you about becoming an actor?

Michael O: I tell them, especially if they are asking for their children. I tell them regardless of how far their child goes in the business or if they even get into the actual business part of it; it teaches you so much. Creativity, to run your own business, listening, collaborate with others, teaches you to be observant, teaches you to be in life’s light when it’s your turn and to not be when it’s not.

TG: We still going to do a show together?

Michael O: You bet!