“Our history is our history.” The statement poured from my mouth as I talked to one of my good friends, an Auburn University alumnus about Auburn University athletic integration pioneers, Henry Harris and James Owens. “Who,” you may ask, as you were not around then, or your memory doesn’t extend back that far.

Let me school you.

First of all, recalling history can sometimes be difficult, especially for those who chose to be on the wrong side of that history. We should never run away from our history. When we do, we can very well repeat it. Maybe in another form or fashion, but we can repeat it. We should also never try to rewrite our history to make it fit the circumstances that make us more comfortable. In loving an institution, such as Auburn, which I do, it is imperative for me to also be objective about it. Our history is our history.

I am not a historian. However, I know what I have lived. I know what I witnessed. I know what I saw others go through. I know how those days of early sports integration made me feel. It’s now been fifty years. Auburn University will honor the feats of these two men with a commemoration during the University’s Annual Black Alumni Weekend.

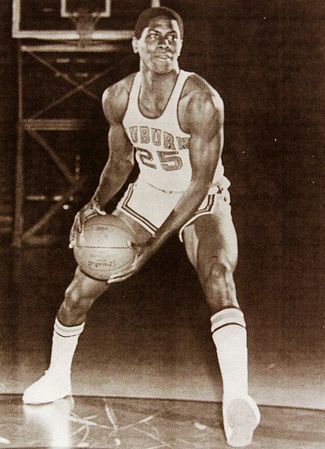

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama was the brave soul who entered first.

Henry broke the color barrier of sports integration at Auburn University in the fall of 1968. It was four years after Auburn University desegregated, due to a court order, by accepting their first and only black student at the time, Harold Franklin. He left three months later.

According to Sam Heys author of Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution: A Story of Hope and Self-Sacrifice in America. Henry was not only the first black athlete at Auburn he was also the first black basketball or football player on scholarship at any of the, then seven, SEC colleges in the Deep South.

Heys writes that Henry’s signing was more than a college sports issue. “Historically it is important to remember that the integration of college sports was as much a civil rights issue as it was an athletic issue. College sports were the final citadel of segregation in the Deep South. Within a year of Auburn making the first move by signing Harris, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi State all integrated their football or basketball programs. LSU and Ole Miss followed within two years of Harris coming to Auburn.”

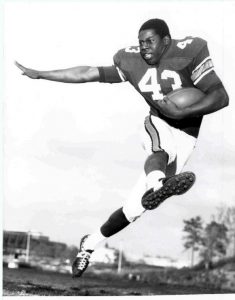

James Owens, from Fairfield, Alabama, walked through the door of sports integration at Auburn next. His chosen sport, football, cast an even brighter spotlight on his integration effort. James often confided to me, that without Henry, he would have left. James said, “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I thought it would be about playing football where I had excelled all my life but this was more than that. I had to be more than a football player. Everything I did was monitored and watched. I was a hero to the blacks. I was a mystery to the whites.”

In 1968, Auburn essentially became the leader in moving toward equality and justice in the Deep South. Sam Heys writes, “Auburn should be proud of the leadership position it took in signing Henry Harris to a basketball scholarship.” Does that mean that Auburn did everything right? NO! There were plenty of rough patches. It does however highlight Auburn’s willingness to step forward before any of their brethren. It also means Henry and James were willing to take that step along with the University. The University, Henry and James became willing leaders in this great cultural experiment.

Did these men have great careers? On the field they were good. They were leaders, not superstars.

Statistically, Henry averaged 12 points 7 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game. He made third team All-SEC after the ‘71-‘72 season.

In the ‘71 and ‘72 seasons, James averaged 5.1 yards from scrimmage, 29 yards on kick returns, 10 yards on pass receptions and 4.1 yards rushing. Not bad considering the few times he got his hands on the ball.

But far more important than their statistics, they led the way. They led their teams and inspired others, including me. They represented the University well. They sacrificed for others. They opened the floodgates. Personally, they became my big brothers when I joined them at Auburn in 1970.

I witnessed their feats on the basketball court and the football field. I also witnessed their hardships, their loneliness, their courage and their despair. While I was at Auburn, Henry never had a roommate. James and I lived together his last year.

These men may never be in any Sports Hall of Fame. They should be! Does changing a segregated way of life compare with running a touchdown or grabbing a rebound? Are you kidding? Is there any comparison? I know my answer. They may never be included with the outstanding athletes whose names are carved in cement on the streets of downtown Auburn or whose busts are included in the SEC Hall of Fame. But they belong there. Plain and simple, they belong there.

(As published on westernjournalism.com, Sept. 28, 2017)

I saw him last spring in Montgomery, Alabama. I was there to speak to a Leadership Montgomery group. As I looked out over the crowd, he sat there, grinning. Grinning at me! Grinning as if he had a secret no one else in the room knew. As it turns out he did. It wasn’t until a few weeks ago, we found the time to get together and talk about it.

The story travels back into not only my past, but also, our mutual history. Back into a time I call yesteryear. Memories fade. Details get fuzzy but the essence of the story, he remembers in full.

We were freshmen at Auburn University. We had at least one class together. We obviously struck up a relationship.

Sam Johnson tells it like this. We both started Auburn in fall 1970. As freshmen we were coming at the early integration of the University from different perspectives. Sam is white. He chose to get to know me. Not just in class and not just as an athlete. Sam chose to befriend me and get to know me in a time when not many on the white side of the integration experiment at Auburn chose to cross over to that other side. He could have chosen to avoid the integration debacle. It wasn’t his fight. He was secure socially in a fraternity and had the advantage of not being the first in his family to venture to Auburn. I was at the other end of that spectrum.

When we met this September, Sam remembers, that we talked a lot in those days; or rather I talked… a lot. Sam says I was angry and voiced my anger to him about the experience between classes while sitting outside of The Haley Center building. Some of that is fuzzy for me but I don’t doubt I was angry. I do wonder about my sharing my feelings with him. That was something I did not do with people I did not know well. It was part of my anger. Integration was lonely, boring, demeaning and more like the drudgery of a miserable mission than a fun education experience. Today when I hear my fellow white alums from that era or teammates tell stories of their college days, I wonder if we went to the same University. The few of us black students who ventured into integration during that time were pioneers on a mission to make things better for those who would follow. Was it fun for us? Nope. The black athletes, at that time there were three of us in the Auburn athletic department (1basketball, 2 football), were the forerunners to today’s games, but we were not the beneficiaries of our efforts. I kept who I was and what I was thinking bottled up inside. My insides were tied up in knots, knots of anger. I often kidded some of my white teammates telling them, “If you knew what I was thinking, you’d be scared of me.” Sam must not have been afraid. Because according to Sam, I let him in.

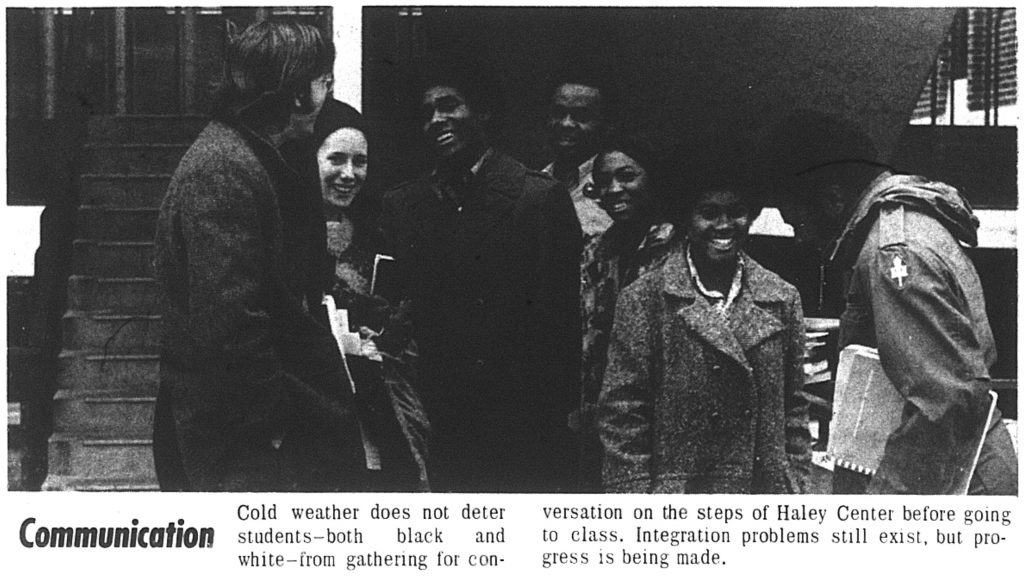

The visible proof of our relationship appeared in the school newspaper, The Plainsman that I would later write for. The paper ran an article on race relations on campus, with an accompanying photo. Sam brought a copy of the photo to our meeting in September. The photo was of Sam and a white female, two other black males: Joe Nathan Allen and Rufus Felton, two black females who I do not remember, and me. We were all smiling. We had been recruited to pose for the picture. Someone walked up to Sam and me and asked if we would pose. Someone else recruited the others. We agreed and met the others on the steps outside Haley Center. In the photo we were all smiling like friends. Sam did not know any of the others, just me.

The cut line under the photo in The Plainsman read, Communication. Cold weather does not deter students both black and white from gathering for conversation on the steps of Haley Center before going to class. Integration problems still exist but progress is being made.

The photo is dated February 12, 1971.

Sam caught hell from some of his fraternity brothers and others for being in the photo with five black students. But he went even further. Because of my venting, Sam took it upon himself to go to the University recruiting office and tell the officials what I had said. Not telling on me but repeating the things that I had said needed to be done to make progress at the University. At first he was given the run around but they eventually listened. Auburn administrators even went so far as to put some things in place to recruit more black students and improve the social atmosphere.

Before we left our September meeting, Sam says that I inspired the little progress that was made in those days. I thank him but know that it was in part, credited to him. I could not have gone and done what he did. I would have been viewed as the angry radical in the administrator’s eyes. I could have lost my spot on the team, lost my scholarship, gotten kicked out of school. On the other hand, Sam would not have known what to say if he had not listened to me. When Sam took it to the administrators it became a university problem not just the angry black guy’s problem. He did what I couldn’t do. It takes us all. Sam taught me that. Thanks Sam!

I never thought I’d write this column. I never knew I’d feel this way. A teammate has passed on and I can’t stop thinking of him. Our journey together brought us a long way. Because we accomplished great things on the football field 40 years ago, the sports media named us, “The Amazins.” As we grew older, had families, and matured, learning to love each other along the way, we coined our own phrase, “Teammates for Life.”

That’s how I feel about David.

David Langner, died Saturday April 26, 2014. He was one helluva football player. A little guy, I often said he was crazy on the football field but if I had the first choice, I’d take David. I’d rather have him on my side than be against him.

David and I traveled a long way in our journey to friendship. I knew him before he knew me. We played against each other in High School. He was a star at Woodlawn High in Birmingham. They were very good. The night we played them they dressed nearly a hundred guys. They came out of their locker room, cocky and proud and ready to feast on the 40 or so players we had from the small Catholic school who had no business on the field with them. David, his brother, his cousin, and their teammates blanked us 39-0 and it wasn’t that close. David, a winner of all kinds of honors, became a highly touted signee of Auburn University.

I walked on at Auburn. One of three blacks on the practice fields of over a hundred players and the only black walkon. David and I didn’t start out as friends.

Walkons have it tough. David didn’t care for the fact that I had dared to walk on to that hallowed ground that he had already earned a spot on. To further confuse things, we had both grown up in Birmingham in the 1960’s when legal segregation meant we could not play ball with or against each other. Friendship was out of the question.

We didn’t get along. David had further to go than I did. We fought often on the field. But we were ballplayers and together we won many games. I won a scholarship and in 1972, we shocked the Southeastern Conference by winning 10 games, losing only once and finishing #5 in the nation. David was a hero that year with his two touchdowns against Alabama in the now famous “Punt Bama Punt” (look it up if you don’t know) game against Alabama. He also led us in interceptions, made All-SEC as a defensive back, and instigated many of the fights we had with other teams. He was a bad ass and we were glad we had him. We always knew he would make a big play.

As we won games, he and I tolerated each other the way teammates will do when they are not friends. Winning does that.

When we were done, he went his way and I went mine. Many years later in Nashville, while filming a Legends of Auburn video, we sat across from each other at dinner. We talked and laughed. He’d already had some health issues and discussed them freely with me. It was a great night for me and, I believe for him. After those many years, we were learning to be friends.

Later, at the thirty-year reunion of “The Amazins,” David came up and gave me a hug. Not one of those quick man hugs but a real hug. He wouldn’t let me go. I hugged him back. I remember standing there in the middle of the floor hugging. Hugging for what seemed like a very long time. That is my favorite memory of my friend David.

Since I heard of his death, I can’t stop thinking of him. I’m proud that we overcame society to be friends.

David will be celebrated for the touchdowns against Alabama, and the great career he had at Auburn. There’s talk that David belongs in the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. You will get no argument from me on that. But most importantly, I will fondly remember the impact we had on each other’s lives. We are teammates for life, and now beyond.