Pat Sullivan!

He was always nice to me and he didn’t have to be.

At John Carroll Catholic High School in 1966 in Birmingham, I was in 9th grade. He was in the 11th. He quarterbacked the football team, had a deadly corner shot in basketball that would easily qualify for today’s three pointers and… oh yeah he was outstanding in baseball.

On football Fridays, Pat and the other football players on varsity could come to school out of uniform, (white shirts, blue tie, charcoal gray pants) and wear their jerseys to class. They paraded like peacocks leading up to the afternoon pep rally and game that night.

On cool days they wore their letter jackets to school. They were cool, studs. Pat wore his with pride. I watched him. I studied him. He was special! Nice! I wanted to play with him. Pat would speak to me and give me a smile. That was important to me, more important than he knew. It was integration. I was a stranger in a strange land, navigating a new world, alone in a crowd. That smile meant and still means a lot.

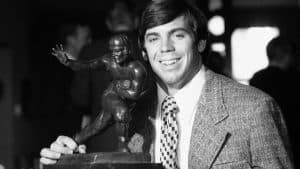

Ultimately, I followed Pat Sullivan to Auburn. There, he again was, “the man,” still without the swagger. Without the arrogance that can sometimes come with being “extra.” He had an incredible career. He won the Heisman Trophy. He gave Auburn fans mental highlights that still flash across the screen in their heads today. He was #7.

I walked on at Auburn. Played freshman ball and got the coaches attention. They asked Pat about me. Imagine, they asked the star player about this black kid who walked on. A kid no one knew. But Pat knew me. He knew me enough to say that I had gone to John Carroll and that I was a good student. Pat told them that everybody liked me and most importantly, I was fast. That spring, I got more than a fair share of repetitions. One day, the coaches put me in for a few plays with the first team offense against the first team defense. I’ll never forget it. It’s great as a young athlete to look up to someone and then actually get to play with him, even if it is “just practice.” It was much more than that to me.

Pat stepped into the huddle and said to the linemen, “Hold them out guys, this one is a touchdown.” THEN… he called my number. I still remember the jitters in my stomach as I jogged out to my position. Surveyed the defense. I got open on a deep post route. Pat let it go. It fell into my arms. I cradled it like a newborn. “Touchdown.” Just like he said. I’ve been a believer ever since.

After that spring, the athletic department awarded me a scholarship. I had a chance to actually play with Pat his senior season. Then the coaches decided to redshirt me. I wanted to play with him! Still, I dressed and traveled every game. What a treat for me! I got to watch Pat up close. In Knoxville, he led us from behind to win 10-9. We ran off the field like we had stolen something. We had a victory. At Georgia, he won the Heisman. What an afternoon. He was the field general, in command. The Auburn fans felt the electricity. His teammates felt it. They would run through walls for him. They believed in him. When Pat ran off the field I waited for him to trade hand slaps.

Other than that magical spring when he threw me the ball every chance he got, I never again played with Pat. But he made me feel like the closet teammate. Great people can make others feel as though their relationship is uniquely special. It’s one-on-one. I felt that way with Pat.

In 2007, I asked Pat if he would write the forward for my book, WalkOn My Reluctant Journey to Integration at Auburn University. He agreed. He wrote in part…

…I try to instill in our players some of the lessons I learned from those times, the journey of life and the foundation a young man can lay for his own future. I use Thom Gossom as an example of a man who had a dream, a vision of himself, that he never gave up against all odds,…

Thank you Pat Sullivan for nurturing that dream and helping to make me possible.

The simple question sent my mind reeling backward through time to those hot, hot, muggy oppressive days of summer. The question was from a neighbor commenting on how hot and uncomfortable the month of July has been. Temperatures have resided in the mid 90s with the heat index well into the 100s.

Ours is a walking, jogging, bike riding neighborhood. People stand in the yard and talk to each other. These days you can do that early morning and late evening but during the middle of the day the heat has been too much. My neighbors question sent my mind back to the heat of yesteryear.

“How did you all stand practicing outdoors in this hot sun? I can’t imagine,” was the question?

I answered immediately, “I don’t know. Sometime I ask myself that question.”

Looking back to the 1970s, it was always brutally hot in Auburn, Alabama in July and August. For clarification, it’s brutally hot in Auburn most summers. But for that five-year period, I was practicing with the football team in the steamy hot sun, with no breeze and only the occasional water break.

Walking on, I had to prove I deserved a scholarship. I did. I had to earn a starters job. I did. I had to keep that job for three years and help us win games and national rankings. I did that too. Standing in the hot sun with my neighbor, I felt a trickle of sweat run across my brow and down my face. Looking back on it now, in a six-decade old body, I wonder how we did it as well.

You see it was about more than being a big man on campus, the glamour of television, or signing autographs. Those were the byproducts, the benefits of hard, grueling, day-to-day grinding work in summer camp. Since school had not started we could devote all our time to practice. Summer camp could make or break our season.

We were young and frisky like colts. Reporting to camp we went at it twice a day for two full weeks before we tapered off to a regular practice schedule. The heat was unbearable. But we were on a mission. We went out in the morning in full pads. We hit, we hit and we hit some more.

In the afternoon practice we did it all over again. Dripping wet with sweat, our pads and practice uniforms now weighed close to ten pounds more as they were soaked. There was no Gatorade. There were no water coolers. It was according to our coaches, “How bad do you want it?”

We did get the occasional water break! People laugh when I tell them we had a water spigot about six inches off the ground that we had to kneel down to slurp its precious cold water on our two water breaks a day. It was yesteryear when the hardship of making a football team was equated with your manhood. “Prove you’re a man,” was the message we were given. If that was what it took to be a man we were willing.

My mom feared for me because I could not hold my weight in that hot sun, running miles and miles a day. I assured her I was okay.

Between practices we stuffed ourselves with food. Caught a quick nap and headed back out for the afternoon practice. Before dressing out we would check the afternoon depth chart. Had anybody moved up on the roster? Had I moved up on the roster?

Inevitably we reached that point in practice where attrition would take hold and those who refused to do it any longer would pack their bags and ease out of their dorm room under the cover of darkness and sneak off to another life. Putting that experience in their rear view mirror. We didn’t hold it against them. Maybe it took more courage to leave than it did to stay.

Was it worth it? Yes! Would I do it again? Yes! Absolutely. Could I do it again at this stage? Absolutely not!

As I explained to my neighbor what that part of my life was like, I smiled as I remembered the angry screams from coaches, the camaraderie we built, the games we won, “the teammates for life” tag we have placed on ourselves. The stories we now tell. All because of that “torture” we underwent in that brutal oppressive heat.

“I don’t see how you all did it,” my neighbor exclaimed.

With youthful exuberance and a big smile, the words shot from my mouth, “It was fun.”

It’s football season! The flags will be flying, notes will be passed in mailboxes, a family will skillfully navigate a football rivalry, and hopefully my next-door neighbor will disappear back into the witness protection program.

Let me explain.

College football season is special in the south. It brings out the child in many of us. Favorite teams, favorite colors, season tickets, tailgating, and talk shows are all staples of the Southern fall pastime. Living in a southern community that is not dominated by any one-college team but instead has supporters of many teams makes for a fun neighborhood once the games kick off. Most of my neighbors aren’t season ticket holders of any one team and don’t go to many games. They all have an affiliation and are occasional game visitors but the television is their dominant viewing pleasure.

On any given Saturday…

My next-door neighbor on the left side of us, an Auburn man, flies his big Auburn flag above the two boats in his boat house on the Choctawhatchee Bay. Two boats you wonder? One is for fun and one for fishing. Doesn’t everyone have two?

On windy days that big ole Auburn flag unfurls beautifully in the wind above the Bay. Kevin, the neighbor, and I visit often across the little fence in our backyards. He is a great neighbor.

Kevin visits Auburn for two or three games a year and on many other Saturdays during the season, he will host viewing parties at his home with lots of friends, beverages and good food. Neighbors drift up to his dock in their boats. Kevin always makes sure we are invited. I did say he is a good neighbor!

Kevin is Auburn through and through but he is not braggadocios or obnoxious. He’s even tempered about the whole thing, and whether Auburn wins or loses, he and his wife Laurie will often load up and go fishing after the game.

Then there’s Marvin.

Marvin went to Georgia. He is my golfing buddy. Marvin is a retired Air Force officer, a good guy and also a great neighbor. Marvin gets more upset over hitting a bad tee shot than he does over a football game. He has on occasion put a note in my mailbox with the score of the game when Georgia wins. The last time he did, it backfired on him. It was a game when Georgia spanked Auburn badly (take your choice of years). I went out to the street to my mailbox and there was a note with the score of the game in bright Georgia colors. I knew immediately Marvin was the culprit. Unfortunately for Marvin, it was a day when the other six guys who I played with at Auburn and who live in the area were all over Kevin’s house. It was a mini-reunion of sorts for us. I took the note in and showed it to them and suggested we go visit Marvin.

Marvin weighs in around 160 pounds. Every one of us easily top 200+. We rang Marvin’s doorbell and waited. I still see his face. None of the guys were smiling. They all had their arms folded and asked, “Are you Marvin? We all played at Auburn.”

He nearly s_ it his britches when I held up the note he’d left and asked in a brusque voice “Marvin did you leave this in my mailbox?” He stammered an inaudible response.

I spoiled it all when I couldn’t hold my laughter any longer and busted out in a loud holler. The guys started laughing, and finally relieved, Marvin realized it was a joke and he laughed. Everyone hugged him and he had the story of a lifetime. Marvin tells me he’s gotten lots of mileage out of that story with his Georgia friends and relatives.

Ken and Sarah have since moved to another neighborhood but their story is interesting. They lived two houses over. Ken is an Auburn grad and Sarah graduated from the University of Alabama. Do I need to say any more? They’ve made it work for nearly 30 years and two children. Ken says on the day of the annual game between Auburn and Alabama they remind each other to be nice. In Auburn’s six-game win streak during the early 2000s Sarah lucked out because Ken was deployed most of the time in the Middle East so she did not have to bear the brunt of his jokes. During the Alabama win streak of late Sarah says Ken finds it convenient to study since he is now involved in a PhD program. “I wish I could watch the game with you,” he fibs. She smiles and walks away. They have a rule. In their family the winner never gloats. A sly smile will do.

There are others.

The lawn service man, an Alabama fan, is deserving of his own story. That one will follow soon. Look for it.

The two Mississippi State families down the street live next door to each other. Between the two houses there are at least seven big pickup trucks. All are Mississippi State maroon. I want to know if the horns on the trucks ring like cowbells when you blow them. I haven’t gotten up the nerve to ask.

And that brings me to my next-door neighbor on the right side of us. Right is generally a word I don’t use in relation to him. He is a dyed in red Alabama fan that out of place in a neighborhood that is fairly easy going about their college football. On game days he dresses in red, hangs his ALABAMA banner out of his back deck, pulls his red vehicles with the red tags and the big white A on their front bumper, in prominent position in his driveway for others to see and struts and sticks his chest out in his red sweatshirt as if he is going to play that day. I doubt seriously if he has ever played, any sport, but don’t confuse him with facts. When Alabama makes good plays you can hear him in his house hollering and cheering up and down the street. When things don’t go well he again hollers but his language is not suitable for this blog.

Alabama has been on a roll these last few years, which has brought him back to college football. In their turbulent years of the late 90s and early 2000s he was “not too much into college football,” according to him. Funny, how winning changes things.

The first year we moved into our house, Alabama won and when I went out to get my morning newspaper, a la Marvin, there was a note with the score of the game in my paper. After that Alabama lost to Auburn six times in a row. There were no notes in my newspaper during those years. After those games he was nowhere to be found. His house would be dark, no lights, no sound, nothing. I told my wife the trauma must have sent him into the witness protection program, and that he moved to Arizona and took a new name.

The neighborhood is again buzzing, flags are flying and possibly notes will be passed among the neighbors. The Mississippi State trucks are rolling up and down the street, a mini-parade. Marvin is sharpening his crayons in anticipation of another Georgia victory over Auburn and if I’m lucky this year, Mr. Alabama fan will once again disappear into witness protection.

The Big O is gone.

My friend. My teammate. The man who helped me through the biggest cultural change of my life is gone. James Curtis Owens died today, March 26, 2016. I knew it was coming. We all knew it was coming. But knowing and living beyond it leaves a hurt and pain deep down in my soul.

I first saw the Big O on a Friday night at John Carroll Athletic Field on Montclair Road in Birmingham, Alabama. I was a junior at John Carroll High School, playing my first full year of organized football. We were a small, rag tag, undersized bunch playing about two classifications above our ability and size level. We didn’t win very often.

The opponent was Fairfield High School. They were good. They had a starter named James Owens, who would later sign with Auburn University, becoming the first African American to integrate a major state university in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi… the Deep South. Now, he was warming up across the field from me. A running back, he was tall, lanky and wore a horse collar around his neck. He was about 6’2” and weighed close to 210 pounds. He looked dangerous. Ready to kick some you know what!

Our coach had warned us about him. He’d then gone on to tell the lie that coaches tell outmanned teams when they are about to get slaughtered by a bigger, faster, better team with bigger, faster, better players.

Referring to Owens, our coach said, “Hey! He’s no better than you. He puts his pants on one leg at a time just like you do.”

We all knew that was bullshit. Putting his pants on like we did had nothing to do with playing the way we did. This guy was All-State in football and track. He ran the 100 hundred-yard dash and threw the shot-put. He was a monster. I was glad as hell I wasn’t on defense.

It wasn’t pretty. He left carnage on the field. I don’t remember the score but it wasn’t close. After it was over, I watched him walk off the field where he had dominated us. Having integrated Fairfield High School football he was now heading off to be one of the first blacks in the Southeastern Conference.

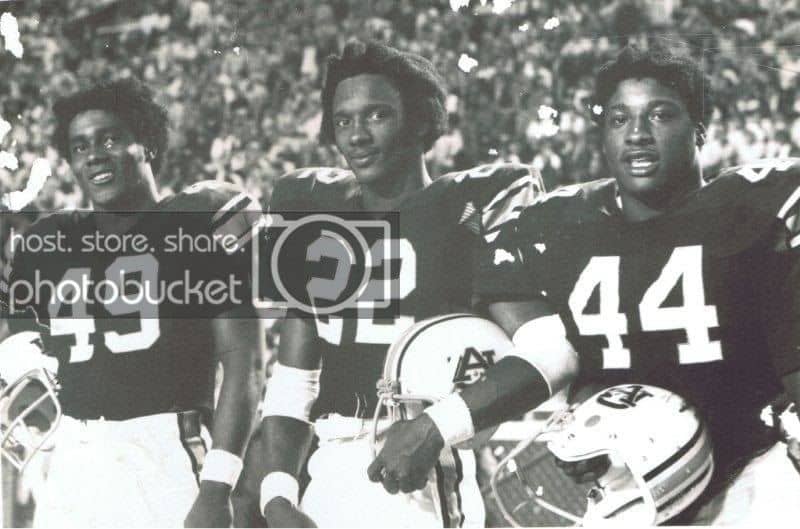

Two years later, I would join James and Virgil Pearson, also from Fairfield, and Auburn’s first African American Athlete, Henry Harris, at Auburn University.

As a basketball player, Henry often travelled in different circles. For Virgil and me, James became our Daddy. We nicknamed him “Daddy O.” He was strong like our fathers, but gentle towards us, who had followed him. We not only respected him, everybody, on and off the field and in the athletic complex, held James in high esteem. Integration made things socially awkward but everybody respected James for his quiet, dignified courage. That respect lasted all of his life.

Our special friendship lasted from 1970 until his death. Like close friends we drifted apart throughout the seasons of our lives but we always found each other again because of the love and respect we had for our shared experience.

Henry left Auburn University after his senior basketball season. Virgil left his sophomore year, looking for a different experience. For the next two years on the varsity football team It was just James and me, as athletes of color. For the rest of his life we always relived that experience.

Between us we realized there was no one else in the world who shared that loneliness, that moment in our lives where we carried the pail of integration uphill without much assistance from those who could have helped us along. Those times were about providing for those whom would follow. We knew that. It kept us going.

James kept me grounded. He talked me down many times when, emotionally, I was way over the top. Over time, we embraced our teammates and they embraced us with that special bond that comes from the shared experiences of being teammates and winning games. During the two years when James and I were the two black pioneers on the team, we won 19 games and lost 3. We were a part of something bigger than us.

Throughout the decades that followed we talked a lot about those times. We always circled back to that experience. What had been a painful part of our lives had become, by the 21st century, a memory of achievement, a gift that we gave to all who followed at our university, not just the black athletes. We also grew to love our teammates and they loved us back. Today we are teammates for life. It ‘s more than a slogan. We live it.

James is an Auburn University icon. He doesn’t need for me to tell everyone about his contributions. Look around the university and you will see his accomplishments in the faces of the young men on the football team, the basketball team, the track team, the baseball team and in the faces of the young women on the softball team, the basketball team and all the other sports that did not exist before integration.

He will always be remembered for what he gave to Auburn University, the state of Alabama and college football. I will always remember him as my friend.

One yard. A big giant step. One yard and your life changes. One yard from glory.

Former ballplayers have the best stories. The good talkers can take an incident from a game many years ago and make it the centerpiece of speeches that they give long after they have finished playing. The “formers,” can be funny, heart wrenching, give inside looks at the teams in their respective eras, inside look at great stars. Randy Campbell is good at it.

Randy is one of the good guys. Today he is a financial advisor in his business Campbell Wealth Management. We serve on the Auburn University Foundation Board together. Imagine that two former football players. We made the transition.

I didn’t know Randy well before he came on the board a year ago. We played in different decades at Auburn. I knew of him. He played quarterback in the 1980s, on some great Auburn teams. He is a great speaker. Randy jokes he was famous for handing off to all-everything runner Bo Jackson. There is some truth to that. Bo was the truth so why not?

Still, Randy was no slouch. He is well remembered. He was 20-4 as a starting quarterback. In the 1983 Tangerine Bowl, he became the answer to a TV trivia question. “The 1983 Tangerine Bowl featured two Heisman Trophy winners, Bo Jackson and Doug Flutie. Who was the MVP?” The answer, Randy Campbell!

Back to Randy’s story. He relishes telling it. It’s like the secret only he thought of.

Here goes.

It’s the 1984 version of the Iron Bowl rivalry game Auburn vs Alabama. It’s a game that Bo will make famous with his “Bo Over the Top” leap at the goal line to give Auburn the victory over Alabama 23-22.

Randy tells the story.

“It’s third down, we’re threatening to score. I throw a swing pass out to Bo. Bo takes it down to the one-yard line. He almost scored. He came up a yard short. Of course he then goes over the top on the next play for the winning touchdown.”

I’m waiting for the punch line. Randy wears his “I’ve got a secret” look on his face.

“If he had scored on the swing pass, instead of “Bo Over the Top,” the headline could have read, “Campbell throws the winning TD in victory over Alabama.” Instead Bo was close, so close, tackled at the one-yard line. Man, I was one yard from glory.”

He looks me in the eye. I grin. It’s a great story. Crowd pleaser. Crowds like self-deprecating humor, especially from athletes who have been at the top of the food chain.

Sports is full of close, almost, damn near, shoulda, woulda, coulda, one play here, one play there type moments. If only such and such, stays safely locked in our memories many years later.

One yard from Glory!

I’ve embellished Randy wanting to be the hero. He is a pretty humble guy. All winning team oriented athletes will tell you, what mattered is that their team won far more than they lost. The team is what counts.

Randy says that. But like many of us “formers” he likes to have fun with his stories.

He says, “I told that story to Bo. I said, ‘Man, if you hadn’t gotten tackled on the one-yard line, the headline would have been “Campbell Tosses Winning TD” instead of Bo Over the Top.’ He wasn’t amused.”

Randy repeated, “Campbell to Jackson for the winning TD.”

He smiled.

I never thought I’d write this column. I never knew I’d feel this way. A teammate has passed on and I can’t stop thinking of him. Our journey together brought us a long way. Because we accomplished great things on the football field 40 years ago, the sports media named us, “The Amazins.” As we grew older, had families, and matured, learning to love each other along the way, we coined our own phrase, “Teammates for Life.”

That’s how I feel about David.

David Langner, died Saturday April 26, 2014. He was one helluva football player. A little guy, I often said he was crazy on the football field but if I had the first choice, I’d take David. I’d rather have him on my side than be against him.

David and I traveled a long way in our journey to friendship. I knew him before he knew me. We played against each other in High School. He was a star at Woodlawn High in Birmingham. They were very good. The night we played them they dressed nearly a hundred guys. They came out of their locker room, cocky and proud and ready to feast on the 40 or so players we had from the small Catholic school who had no business on the field with them. David, his brother, his cousin, and their teammates blanked us 39-0 and it wasn’t that close. David, a winner of all kinds of honors, became a highly touted signee of Auburn University.

I walked on at Auburn. One of three blacks on the practice fields of over a hundred players and the only black walkon. David and I didn’t start out as friends.

Walkons have it tough. David didn’t care for the fact that I had dared to walk on to that hallowed ground that he had already earned a spot on. To further confuse things, we had both grown up in Birmingham in the 1960’s when legal segregation meant we could not play ball with or against each other. Friendship was out of the question.

We didn’t get along. David had further to go than I did. We fought often on the field. But we were ballplayers and together we won many games. I won a scholarship and in 1972, we shocked the Southeastern Conference by winning 10 games, losing only once and finishing #5 in the nation. David was a hero that year with his two touchdowns against Alabama in the now famous “Punt Bama Punt” (look it up if you don’t know) game against Alabama. He also led us in interceptions, made All-SEC as a defensive back, and instigated many of the fights we had with other teams. He was a bad ass and we were glad we had him. We always knew he would make a big play.

As we won games, he and I tolerated each other the way teammates will do when they are not friends. Winning does that.

When we were done, he went his way and I went mine. Many years later in Nashville, while filming a Legends of Auburn video, we sat across from each other at dinner. We talked and laughed. He’d already had some health issues and discussed them freely with me. It was a great night for me and, I believe for him. After those many years, we were learning to be friends.

Later, at the thirty-year reunion of “The Amazins,” David came up and gave me a hug. Not one of those quick man hugs but a real hug. He wouldn’t let me go. I hugged him back. I remember standing there in the middle of the floor hugging. Hugging for what seemed like a very long time. That is my favorite memory of my friend David.

Since I heard of his death, I can’t stop thinking of him. I’m proud that we overcame society to be friends.

David will be celebrated for the touchdowns against Alabama, and the great career he had at Auburn. There’s talk that David belongs in the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. You will get no argument from me on that. But most importantly, I will fondly remember the impact we had on each other’s lives. We are teammates for life, and now beyond.

If work is supposed to be fun, I’m having a ball. For the past year I’ve been working on a project that feeds my soul and in the words of the old Native American Chief in the film Little Big Man “causes my heart to soar like a hawk.” Quiet Courage, a film documentary on my good friend James Owens gets my juices flowing.

James Owens has been my friend since 1970. We were pioneers of college football integration at Auburn University. When we played black players in the Southeastern conference of college football were relegated to one or two per team.

In comparison to James I had it easy. He was the first African American football player in Auburn’s history.

The loneliness, the slurs, the suppression of hurts and emotions stayed with me a long time. It was three decades before I could express it in this manner or any manner. It was many years before I could bring myself to talk about it with my wife and son. Just couldn’t. It was too painful.

But this isn’t about me: Nor about the pain. It’s about my friend and his forty-year relationship with Auburn University.

“I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” James tells me. “I had no idea of the magnitude of being the first black.”

In 1969, James Owens realized a portion of Martin Luther King’s dream. He fulfilled the legacy of Jackie Robinson. He answered prayers of many blacks and some whites in the state of Alabama by answering Auburn’s call to play football at the University. What has followed over the last forty years is a love story.

Not knowing what to do to aid their only black football player and only the second black athlete in Auburn Athletic history, Auburn attempted to treat James as if he was no different than the other athletes. “We treat all our athletes the same” was the philosophy.

Imagine being the only white among a team of blacks. Imagine being the only white in a University of 15,000 blacks where everyone, students, alumni, whites and blacks examine your every move. Imagine there are so few people who look like you on the campus, that your social life consists of sitting in the TV room after games while all your teammates are out partying and enjoying the spoils of victory. Imagine being seventeen and having no family, nearby. Imagine possessing a second rate education, a by-product of segregation that leaves you inadequate in the classroom. Imagine.

Quiet Courage explores these issues and others as told by James, his teammates former coaches and friends. It’s introspective, funny, sad, and full of love. Mistakes were made. James did not graduate. He didn’t play professional football. The University brought him back as a graduate assistant to get his degree. The rules were changed and he was asked to leave. He wandered. Jobs came and went. His wife Gloria who he met when she became one of the few black women at Auburn his senior year, became his salvation.

Then he found the ministry. Saving souls was as tough as scoring against bigotry, but it was more rewarding. His church was only forty miles from where he’d made history, but he didn’t venture close to campus. Nor did the University reach out to him. Love relationships are like that.

Fate intervened. His nephew, Ladarious signed a scholarship to play football at Auburn. James was drawn back to his Alma Mater. This time it was different. Auburn loved him back. Auburn Athletics created the James Owens Award of Courage to honor him. He received his award and a standing ovation in front of 86,00 Auburn fans. Auburn named him an Auburn legend and he was honored at the SEC Legends dinner with other legends from the conference before the 2012 championship game.

Life was good. He was back in the fold. His teammates honored him as the soul of the 10-1, 1972 team known as the Amazins, one of the favored teams in Auburn history.

Then came the diagnosis. His heart was failing. Tears followed. His teammates and the University rallied to his side. Letters, phone calls, and loads of love poured in.

Yes. He realized, they loved him, not only as a football player but, as James Owens, the human being who notched his name in the Auburn history book.

He had one regret. He never received his degree.

The phone call from the Auburn administrators shocked him. The robe, the march, the arena full of the Auburn family, his name called, the honorary degree handed to him, his acceptance speech. He was an Auburn University graduate.

They were back together again, a happy ending. Just like in the movies.