“Our history is our history.” The statement poured from my mouth as I talked to one of my good friends, an Auburn University alumnus about Auburn University athletic integration pioneers, Henry Harris and James Owens. “Who,” you may ask, as you were not around then, or your memory doesn’t extend back that far.

Let me school you.

First of all, recalling history can sometimes be difficult, especially for those who chose to be on the wrong side of that history. We should never run away from our history. When we do, we can very well repeat it. Maybe in another form or fashion, but we can repeat it. We should also never try to rewrite our history to make it fit the circumstances that make us more comfortable. In loving an institution, such as Auburn, which I do, it is imperative for me to also be objective about it. Our history is our history.

I am not a historian. However, I know what I have lived. I know what I witnessed. I know what I saw others go through. I know how those days of early sports integration made me feel. It’s now been fifty years. Auburn University will honor the feats of these two men with a commemoration during the University’s Annual Black Alumni Weekend.

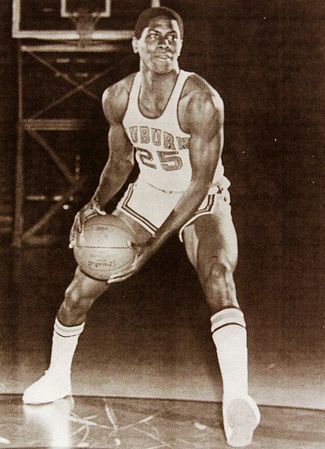

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama was the brave soul who entered first.

Henry broke the color barrier of sports integration at Auburn University in the fall of 1968. It was four years after Auburn University desegregated, due to a court order, by accepting their first and only black student at the time, Harold Franklin. He left three months later.

According to Sam Heys author of Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution: A Story of Hope and Self-Sacrifice in America. Henry was not only the first black athlete at Auburn he was also the first black basketball or football player on scholarship at any of the, then seven, SEC colleges in the Deep South.

Heys writes that Henry’s signing was more than a college sports issue. “Historically it is important to remember that the integration of college sports was as much a civil rights issue as it was an athletic issue. College sports were the final citadel of segregation in the Deep South. Within a year of Auburn making the first move by signing Harris, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi State all integrated their football or basketball programs. LSU and Ole Miss followed within two years of Harris coming to Auburn.”

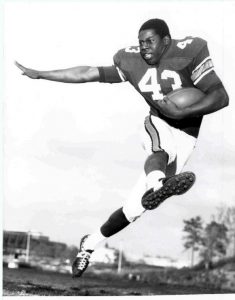

James Owens, from Fairfield, Alabama, walked through the door of sports integration at Auburn next. His chosen sport, football, cast an even brighter spotlight on his integration effort. James often confided to me, that without Henry, he would have left. James said, “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I thought it would be about playing football where I had excelled all my life but this was more than that. I had to be more than a football player. Everything I did was monitored and watched. I was a hero to the blacks. I was a mystery to the whites.”

In 1968, Auburn essentially became the leader in moving toward equality and justice in the Deep South. Sam Heys writes, “Auburn should be proud of the leadership position it took in signing Henry Harris to a basketball scholarship.” Does that mean that Auburn did everything right? NO! There were plenty of rough patches. It does however highlight Auburn’s willingness to step forward before any of their brethren. It also means Henry and James were willing to take that step along with the University. The University, Henry and James became willing leaders in this great cultural experiment.

Did these men have great careers? On the field they were good. They were leaders, not superstars.

Statistically, Henry averaged 12 points 7 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game. He made third team All-SEC after the ‘71-‘72 season.

In the ‘71 and ‘72 seasons, James averaged 5.1 yards from scrimmage, 29 yards on kick returns, 10 yards on pass receptions and 4.1 yards rushing. Not bad considering the few times he got his hands on the ball.

But far more important than their statistics, they led the way. They led their teams and inspired others, including me. They represented the University well. They sacrificed for others. They opened the floodgates. Personally, they became my big brothers when I joined them at Auburn in 1970.

I witnessed their feats on the basketball court and the football field. I also witnessed their hardships, their loneliness, their courage and their despair. While I was at Auburn, Henry never had a roommate. James and I lived together his last year.

These men may never be in any Sports Hall of Fame. They should be! Does changing a segregated way of life compare with running a touchdown or grabbing a rebound? Are you kidding? Is there any comparison? I know my answer. They may never be included with the outstanding athletes whose names are carved in cement on the streets of downtown Auburn or whose busts are included in the SEC Hall of Fame. But they belong there. Plain and simple, they belong there.

The simple question sent my mind reeling backward through time to those hot, hot, muggy oppressive days of summer. The question was from a neighbor commenting on how hot and uncomfortable the month of July has been. Temperatures have resided in the mid 90s with the heat index well into the 100s.

Ours is a walking, jogging, bike riding neighborhood. People stand in the yard and talk to each other. These days you can do that early morning and late evening but during the middle of the day the heat has been too much. My neighbors question sent my mind back to the heat of yesteryear.

“How did you all stand practicing outdoors in this hot sun? I can’t imagine,” was the question?

I answered immediately, “I don’t know. Sometime I ask myself that question.”

Looking back to the 1970s, it was always brutally hot in Auburn, Alabama in July and August. For clarification, it’s brutally hot in Auburn most summers. But for that five-year period, I was practicing with the football team in the steamy hot sun, with no breeze and only the occasional water break.

Walking on, I had to prove I deserved a scholarship. I did. I had to earn a starters job. I did. I had to keep that job for three years and help us win games and national rankings. I did that too. Standing in the hot sun with my neighbor, I felt a trickle of sweat run across my brow and down my face. Looking back on it now, in a six-decade old body, I wonder how we did it as well.

You see it was about more than being a big man on campus, the glamour of television, or signing autographs. Those were the byproducts, the benefits of hard, grueling, day-to-day grinding work in summer camp. Since school had not started we could devote all our time to practice. Summer camp could make or break our season.

We were young and frisky like colts. Reporting to camp we went at it twice a day for two full weeks before we tapered off to a regular practice schedule. The heat was unbearable. But we were on a mission. We went out in the morning in full pads. We hit, we hit and we hit some more.

In the afternoon practice we did it all over again. Dripping wet with sweat, our pads and practice uniforms now weighed close to ten pounds more as they were soaked. There was no Gatorade. There were no water coolers. It was according to our coaches, “How bad do you want it?”

We did get the occasional water break! People laugh when I tell them we had a water spigot about six inches off the ground that we had to kneel down to slurp its precious cold water on our two water breaks a day. It was yesteryear when the hardship of making a football team was equated with your manhood. “Prove you’re a man,” was the message we were given. If that was what it took to be a man we were willing.

My mom feared for me because I could not hold my weight in that hot sun, running miles and miles a day. I assured her I was okay.

Between practices we stuffed ourselves with food. Caught a quick nap and headed back out for the afternoon practice. Before dressing out we would check the afternoon depth chart. Had anybody moved up on the roster? Had I moved up on the roster?

Inevitably we reached that point in practice where attrition would take hold and those who refused to do it any longer would pack their bags and ease out of their dorm room under the cover of darkness and sneak off to another life. Putting that experience in their rear view mirror. We didn’t hold it against them. Maybe it took more courage to leave than it did to stay.

Was it worth it? Yes! Would I do it again? Yes! Absolutely. Could I do it again at this stage? Absolutely not!

As I explained to my neighbor what that part of my life was like, I smiled as I remembered the angry screams from coaches, the camaraderie we built, the games we won, “the teammates for life” tag we have placed on ourselves. The stories we now tell. All because of that “torture” we underwent in that brutal oppressive heat.

“I don’t see how you all did it,” my neighbor exclaimed.

With youthful exuberance and a big smile, the words shot from my mouth, “It was fun.”

It was August 2011! I’ll never forget counting down the days until I left. It was so sad…but it was so exciting, so major, I couldn’t wait for the day. I said my “proper goodbyes” to most of my friends. That morning I hugged my mom and my Nana, and dad and I got in my packed down car and started our 765 mile road trip to a place where I had only been once, and didn’t know a soul.

After ~about~ 12 hours in the car, dad and I made it to our hotel. I remember coming off the exit and seeing a Golden Corral (ugh! Haha), a WalMart, and then getting to the Jameson Inn. We had made it to Auburn, Alabama. This was my new home. Hungry, we asked where we should eat…the recommendation…Niffer’s! We got fried pickles and I signed the wall somewhere near the bar. After we ate, we went back to the hotel and settled in for the night. At some point, one of us made a comment about the TV, or clock, or cell phones or something being a different time. Without thinking I said, “well maybe we’re in a different time zone,” and after a few seconds, we realized we were! (lol)

Auburn had just won the National Championship in January, and you couldn’t drive by, or walk in, anywhere without the store, signs along the road, or the items in every store letting you know. I watched the game with a group of friends after attending a Fort Hill basketball game (I think?). When it was getting down to the end, we joked that whichever school won is where I would go to college. That’s not the reason I went to Auburn, but isn’t that funny?

I moved into my apartment, started my classes, made a few friends, and quickly got a job. I got hired at the Sonic on South College. It lasted less than a week. Turns out an unorganized store and $4.14 an hour wasn’t for me. I called and quit the Friday before the first Auburn game.

On September 3rd, Utah State came to Jordan-Hare. All I could do was take it all in. RVs full of people tailgating, cars parked all over the place, and people in orange (and some blue) were everywhere. It was an “All Orange” game, so I wore my new orange Auburn shirt. I climbed all the way to the top of the stadium, and for the first time- I saw the Eagle fly, listened & participated in the stadium-wide Auburn call cheers, and watched the marching band in awe. If you ever go to an Auburn game, DO NOT miss pregame, it’s the best part!

The Auburn Marching Band during pre-game.

The game went on, and boy, if that first game wasn’t a perfect metaphor for my new life as an Auburn fan. I’ve learned to hope for the best and expect anything. We beat Utah State 42-38, and I went out and bought myself a pair of orange Chuck Taylors in celebration.

Who knew I’d ever own this much orange?

Even though I didn’t know it yet, the “Auburn Family” was a real thing. My Auburn Family welcomed me, an outsider, and taught me all the things I needed to know. They welcomed me to their tailgates, they invited me to games with them, they taught me the cheers, the songs, the traditions, and they showed me what a real Auburn fan was.

I can’t believe that was seven years ago. There were so many new experiences and so many changes I have experienced since then. But as we prepare for another football season, I look back at those milestone moments as a Auburn student and fan.

On a Friday night, before a Saturday Auburn football game, at the busy, crowded Auburn Hotel and Conference Center, I heard my name called as I entered the lounge. “Hey Thom, come on over here and sit down.” It was a command as much as a request. Charles Barkley was parked in a corner holding court with several guys sitting around him, including another Auburn basketball Legend, Chuck Person, “The Rifleman,” who is now on the Auburn basketball staff. My friend Mychal and I joined them and let’s just say it was a memorable evening.

Charles held court, a king on his throne as he sat with his back to the wall able to see all who entered his domain. For the next couple of hours our laughter rocked the lounge as we cracked jokes at each other’s expense, expounded on sports and politics, enjoyed several beers and pizzas, and of course listened to Charles.

In a crack aimed at me he blurted out to a nearby waitress, “Yeah, I’m out with my Grandfather tonight.” Everybody got a big laugh at my expense. It was that kind of night.

Charles loves Auburn and its people and proved it by posing for at least 50 pictures that night with whomever came forward to ask, children, men, women, past acquaintances and anyone who wandered into the room, discovered that Big Charles was in the house and wanted a photo. Often they would interrupt our conversations, yet Charles was always gracious and we would make room for the person to enter our little domain and get the photo op. I admire his graciousness. He made all who asked feel special.

Charles was in town for the game but also for the announcement that Auburn athletics would honor him with a statue in front of the basketball arena much like the statues of Heisman Trophy winners Bo Jackson, Pat Sullivan and Cam Newton grace the outside of the football stadium. The weekend also included the Bruce (Pearl) and Barkley golf tournament played that Monday with some 120 golfers competing from around the area in support of Auburn basketball.

In typical Charles fashion he asked that his statue be made from a younger picture of him when, as he termed it, “I was skinny.”

“Must be a baby picture,” one of the guys quipped.

The laughter rocked the lounge.

The fun continued throughout the evening.

“I was the leading rebounder in the SEC, when I played with Chuck (Person).” We waited for the punch line. Charles delivered. “Hell it was the only way I could get a shot. Chuck would put it up, baby.”

Chuck could only laugh.

I met Charles for the first time a few years ago. We were both speaking at a conference in Montgomery. I approached him and extended my hand to shake and he put me in a bear hug and held on to me all the while saying “Thank you.”

Puzzled I asked, “For what?”

“You know what you did,” he responded.

“You and the first brothers to come to Auburn made it possible for us.” He responded, referring to the integration of Auburn sports in the late 1960s and early 1970s and those athletes like himself who came behind us early pioneers.

“Thank you.” He said again.

I’ve never forgotten that and never will. That recognition is as important to me as any statue could ever be.

Since then we have been friends, comfortable enough for him to crack me about being his grandfather.

After a couple of hours we drifted up the street to another bar restaurant in downtown Auburn. With Chuck Person having left because of an early morning basketball practice five of us headed up the sidewalk. Heads turned as Charles led the way. A couple of people stopped me to shake hands and relay an Auburn anecdote.

“Hey Charles,” I called out to him as we walked up College Street. “Yeah?” he answered. “Look at all these people looking at us,” I began. I waited until I had all the guy’s attention and then stated. “They’re trying to figure out who the big guy is walking with Thom.” The guys laughed, especially Charles.

As the evening wound down, Charles and a couple of the others decided they would check out another spot before heading back to the hotel. I begged off. Charles couldn’t resist. “Yeah, I know your wife,” he laughed. “Better get on home before you get a whipping.”

I hugged him. It had been a great evening.

Bryan, the truck operator for the lawn and pest control company, arrives for his monthly treatment of the lawn. He’s been coming now for about 5 years. He wears his customary, dirty, oil stained Alabama Crimson Tide cap pulled tightly and low on his head. The cap is old, worn and he is never without it.

Bryan’s ritual is to back his big, liquid, lawn treatment filled truck into the driveway and pull into the space we reserve for him. Before doing anything, he saunters over to the front door and rings the doorbell just to announce that he is there, a practice I think is pretty cool.

Bryan walks slowly. He talks a lot. He talks slowly, has a deep voice, and is never in a hurry. Did I say he talks a lot? It’s not good to get caught out in the yard when Bryan arrives. Thirty minutes to an hour, gone. If he was getting paid by the word…

Today isn’t my day!

Bryan catches me driving in. He waits at my car door. Ready to talk. I slowly exit the car. Before I can speak, he begins.

Bryan: You didn’t tell me. Man, I can’t believe you didn’t tell me!

TG: What?

Bryan: You played at Auburn!

TG: Oh. Man. Yeah. It was a long time ago!

Bryan: Naw! Really! Wow that’s cool, dude. But you know, I keep up with it, but… I’m not really into it like that.

TG: (Starts to walk off) Hey, Okay.

Bryan: I wear this Alabama cap. (Beat) I follow Alabama. (Beat) Watch all the games. (Beat) Wear my jersey on game day. (Beat) Get the kids all psyched up. My ole lady, she a Bama fan… (Pause) But, You know. Some people just can’t let it go.

TG: (Again starts to walk off) Yeah, I know.

Brian: (Following TG as he starts to walk toward the door) People see me with the Alabama cap, (he shrugs), but… I’m not really into it like that.

Brian: (Confesses) (Pause) Got a couple of stickers on my car, well at least four stickers…. I started to put a Saban sticker on it but… I didn’t want to overdo it.

Like this cap. Had it twenty years. I got a Alabama room in my house. Posters. Pennants. Got some neat stuff. My friend got his whole house decorated.

TG: Okay Bryan, I’ll see you. I’ve got to get to work.

Bryan: You know I try and keep it all on an even keel. Not get too much into it like that. You know.

Bryan: So did you want to play at Alabama? (He laughs). Hey! Hey! Hey! I’m just kidding. Hey! Hey! Hey!

TG: No. Not really.

Brian: Well, ya’ll got some good recruits this year. But Hey! We got another number one class. Hey! Hey! Hey! So, we starting out the season good. (Beat) Hey, you guys lost a tough one. Hey! Hey! Hey!

TG: Uh uh!

Bryan: You heard about this prospect in the second grade. I mean I don’t keep up with it that young. But…Think we gon offer him. Say he gon be real special. Let’s go ahead and sew him up. You know. May as well. Mama went to Auburn but hey, I betcha in ten years you see him in a Bama uniform. Hey! Hey! Hey! You know what I’m saying.

TG: Yeah.

Bryan: (pause) I guess I better get busy.

TG: Okay! See you buddy.

Bryan: (Heads toward the truck). Put my cap in the truck, don’t want it to get sweaty. My Daddy got this cap for me one time when he was on campus doing some construction work. Never been myself.

TG: Where?

Bryan: …to the campus. You know. One day I’m going. (Beat) What cha think about the game this weekend? We twelve point favorites. I don’t bet though. Saving up. Told the ole lady we gon get a new flat screen. Sit in my special room. She come in there some time. You know. Hey! Hey! Hey! She ain’t really into it like that.

It’s football season! The flags will be flying, notes will be passed in mailboxes, a family will skillfully navigate a football rivalry, and hopefully my next-door neighbor will disappear back into the witness protection program.

Let me explain.

College football season is special in the south. It brings out the child in many of us. Favorite teams, favorite colors, season tickets, tailgating, and talk shows are all staples of the Southern fall pastime. Living in a southern community that is not dominated by any one-college team but instead has supporters of many teams makes for a fun neighborhood once the games kick off. Most of my neighbors aren’t season ticket holders of any one team and don’t go to many games. They all have an affiliation and are occasional game visitors but the television is their dominant viewing pleasure.

On any given Saturday…

My next-door neighbor on the left side of us, an Auburn man, flies his big Auburn flag above the two boats in his boat house on the Choctawhatchee Bay. Two boats you wonder? One is for fun and one for fishing. Doesn’t everyone have two?

On windy days that big ole Auburn flag unfurls beautifully in the wind above the Bay. Kevin, the neighbor, and I visit often across the little fence in our backyards. He is a great neighbor.

Kevin visits Auburn for two or three games a year and on many other Saturdays during the season, he will host viewing parties at his home with lots of friends, beverages and good food. Neighbors drift up to his dock in their boats. Kevin always makes sure we are invited. I did say he is a good neighbor!

Kevin is Auburn through and through but he is not braggadocios or obnoxious. He’s even tempered about the whole thing, and whether Auburn wins or loses, he and his wife Laurie will often load up and go fishing after the game.

Then there’s Marvin.

Marvin went to Georgia. He is my golfing buddy. Marvin is a retired Air Force officer, a good guy and also a great neighbor. Marvin gets more upset over hitting a bad tee shot than he does over a football game. He has on occasion put a note in my mailbox with the score of the game when Georgia wins. The last time he did, it backfired on him. It was a game when Georgia spanked Auburn badly (take your choice of years). I went out to the street to my mailbox and there was a note with the score of the game in bright Georgia colors. I knew immediately Marvin was the culprit. Unfortunately for Marvin, it was a day when the other six guys who I played with at Auburn and who live in the area were all over Kevin’s house. It was a mini-reunion of sorts for us. I took the note in and showed it to them and suggested we go visit Marvin.

Marvin weighs in around 160 pounds. Every one of us easily top 200+. We rang Marvin’s doorbell and waited. I still see his face. None of the guys were smiling. They all had their arms folded and asked, “Are you Marvin? We all played at Auburn.”

He nearly s_ it his britches when I held up the note he’d left and asked in a brusque voice “Marvin did you leave this in my mailbox?” He stammered an inaudible response.

I spoiled it all when I couldn’t hold my laughter any longer and busted out in a loud holler. The guys started laughing, and finally relieved, Marvin realized it was a joke and he laughed. Everyone hugged him and he had the story of a lifetime. Marvin tells me he’s gotten lots of mileage out of that story with his Georgia friends and relatives.

Ken and Sarah have since moved to another neighborhood but their story is interesting. They lived two houses over. Ken is an Auburn grad and Sarah graduated from the University of Alabama. Do I need to say any more? They’ve made it work for nearly 30 years and two children. Ken says on the day of the annual game between Auburn and Alabama they remind each other to be nice. In Auburn’s six-game win streak during the early 2000s Sarah lucked out because Ken was deployed most of the time in the Middle East so she did not have to bear the brunt of his jokes. During the Alabama win streak of late Sarah says Ken finds it convenient to study since he is now involved in a PhD program. “I wish I could watch the game with you,” he fibs. She smiles and walks away. They have a rule. In their family the winner never gloats. A sly smile will do.

There are others.

The lawn service man, an Alabama fan, is deserving of his own story. That one will follow soon. Look for it.

The two Mississippi State families down the street live next door to each other. Between the two houses there are at least seven big pickup trucks. All are Mississippi State maroon. I want to know if the horns on the trucks ring like cowbells when you blow them. I haven’t gotten up the nerve to ask.

And that brings me to my next-door neighbor on the right side of us. Right is generally a word I don’t use in relation to him. He is a dyed in red Alabama fan that out of place in a neighborhood that is fairly easy going about their college football. On game days he dresses in red, hangs his ALABAMA banner out of his back deck, pulls his red vehicles with the red tags and the big white A on their front bumper, in prominent position in his driveway for others to see and struts and sticks his chest out in his red sweatshirt as if he is going to play that day. I doubt seriously if he has ever played, any sport, but don’t confuse him with facts. When Alabama makes good plays you can hear him in his house hollering and cheering up and down the street. When things don’t go well he again hollers but his language is not suitable for this blog.

Alabama has been on a roll these last few years, which has brought him back to college football. In their turbulent years of the late 90s and early 2000s he was “not too much into college football,” according to him. Funny, how winning changes things.

The first year we moved into our house, Alabama won and when I went out to get my morning newspaper, a la Marvin, there was a note with the score of the game in my paper. After that Alabama lost to Auburn six times in a row. There were no notes in my newspaper during those years. After those games he was nowhere to be found. His house would be dark, no lights, no sound, nothing. I told my wife the trauma must have sent him into the witness protection program, and that he moved to Arizona and took a new name.

The neighborhood is again buzzing, flags are flying and possibly notes will be passed among the neighbors. The Mississippi State trucks are rolling up and down the street, a mini-parade. Marvin is sharpening his crayons in anticipation of another Georgia victory over Auburn and if I’m lucky this year, Mr. Alabama fan will once again disappear into witness protection.

The Big O is gone.

My friend. My teammate. The man who helped me through the biggest cultural change of my life is gone. James Curtis Owens died today, March 26, 2016. I knew it was coming. We all knew it was coming. But knowing and living beyond it leaves a hurt and pain deep down in my soul.

I first saw the Big O on a Friday night at John Carroll Athletic Field on Montclair Road in Birmingham, Alabama. I was a junior at John Carroll High School, playing my first full year of organized football. We were a small, rag tag, undersized bunch playing about two classifications above our ability and size level. We didn’t win very often.

The opponent was Fairfield High School. They were good. They had a starter named James Owens, who would later sign with Auburn University, becoming the first African American to integrate a major state university in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi… the Deep South. Now, he was warming up across the field from me. A running back, he was tall, lanky and wore a horse collar around his neck. He was about 6’2” and weighed close to 210 pounds. He looked dangerous. Ready to kick some you know what!

Our coach had warned us about him. He’d then gone on to tell the lie that coaches tell outmanned teams when they are about to get slaughtered by a bigger, faster, better team with bigger, faster, better players.

Referring to Owens, our coach said, “Hey! He’s no better than you. He puts his pants on one leg at a time just like you do.”

We all knew that was bullshit. Putting his pants on like we did had nothing to do with playing the way we did. This guy was All-State in football and track. He ran the 100 hundred-yard dash and threw the shot-put. He was a monster. I was glad as hell I wasn’t on defense.

It wasn’t pretty. He left carnage on the field. I don’t remember the score but it wasn’t close. After it was over, I watched him walk off the field where he had dominated us. Having integrated Fairfield High School football he was now heading off to be one of the first blacks in the Southeastern Conference.

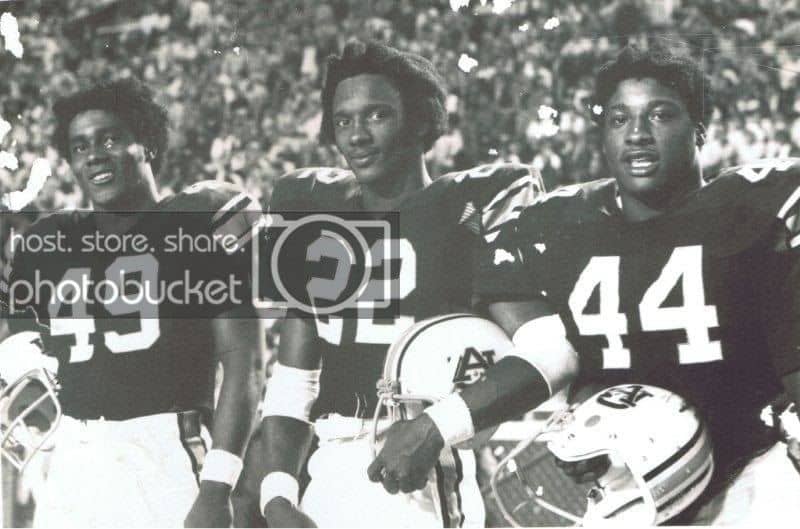

Two years later, I would join James and Virgil Pearson, also from Fairfield, and Auburn’s first African American Athlete, Henry Harris, at Auburn University.

As a basketball player, Henry often travelled in different circles. For Virgil and me, James became our Daddy. We nicknamed him “Daddy O.” He was strong like our fathers, but gentle towards us, who had followed him. We not only respected him, everybody, on and off the field and in the athletic complex, held James in high esteem. Integration made things socially awkward but everybody respected James for his quiet, dignified courage. That respect lasted all of his life.

Our special friendship lasted from 1970 until his death. Like close friends we drifted apart throughout the seasons of our lives but we always found each other again because of the love and respect we had for our shared experience.

Henry left Auburn University after his senior basketball season. Virgil left his sophomore year, looking for a different experience. For the next two years on the varsity football team It was just James and me, as athletes of color. For the rest of his life we always relived that experience.

Between us we realized there was no one else in the world who shared that loneliness, that moment in our lives where we carried the pail of integration uphill without much assistance from those who could have helped us along. Those times were about providing for those whom would follow. We knew that. It kept us going.

James kept me grounded. He talked me down many times when, emotionally, I was way over the top. Over time, we embraced our teammates and they embraced us with that special bond that comes from the shared experiences of being teammates and winning games. During the two years when James and I were the two black pioneers on the team, we won 19 games and lost 3. We were a part of something bigger than us.

Throughout the decades that followed we talked a lot about those times. We always circled back to that experience. What had been a painful part of our lives had become, by the 21st century, a memory of achievement, a gift that we gave to all who followed at our university, not just the black athletes. We also grew to love our teammates and they loved us back. Today we are teammates for life. It ‘s more than a slogan. We live it.

James is an Auburn University icon. He doesn’t need for me to tell everyone about his contributions. Look around the university and you will see his accomplishments in the faces of the young men on the football team, the basketball team, the track team, the baseball team and in the faces of the young women on the softball team, the basketball team and all the other sports that did not exist before integration.

He will always be remembered for what he gave to Auburn University, the state of Alabama and college football. I will always remember him as my friend.

I never thought I’d write this column. I never knew I’d feel this way. A teammate has passed on and I can’t stop thinking of him. Our journey together brought us a long way. Because we accomplished great things on the football field 40 years ago, the sports media named us, “The Amazins.” As we grew older, had families, and matured, learning to love each other along the way, we coined our own phrase, “Teammates for Life.”

That’s how I feel about David.

David Langner, died Saturday April 26, 2014. He was one helluva football player. A little guy, I often said he was crazy on the football field but if I had the first choice, I’d take David. I’d rather have him on my side than be against him.

David and I traveled a long way in our journey to friendship. I knew him before he knew me. We played against each other in High School. He was a star at Woodlawn High in Birmingham. They were very good. The night we played them they dressed nearly a hundred guys. They came out of their locker room, cocky and proud and ready to feast on the 40 or so players we had from the small Catholic school who had no business on the field with them. David, his brother, his cousin, and their teammates blanked us 39-0 and it wasn’t that close. David, a winner of all kinds of honors, became a highly touted signee of Auburn University.

I walked on at Auburn. One of three blacks on the practice fields of over a hundred players and the only black walkon. David and I didn’t start out as friends.

Walkons have it tough. David didn’t care for the fact that I had dared to walk on to that hallowed ground that he had already earned a spot on. To further confuse things, we had both grown up in Birmingham in the 1960’s when legal segregation meant we could not play ball with or against each other. Friendship was out of the question.

We didn’t get along. David had further to go than I did. We fought often on the field. But we were ballplayers and together we won many games. I won a scholarship and in 1972, we shocked the Southeastern Conference by winning 10 games, losing only once and finishing #5 in the nation. David was a hero that year with his two touchdowns against Alabama in the now famous “Punt Bama Punt” (look it up if you don’t know) game against Alabama. He also led us in interceptions, made All-SEC as a defensive back, and instigated many of the fights we had with other teams. He was a bad ass and we were glad we had him. We always knew he would make a big play.

As we won games, he and I tolerated each other the way teammates will do when they are not friends. Winning does that.

When we were done, he went his way and I went mine. Many years later in Nashville, while filming a Legends of Auburn video, we sat across from each other at dinner. We talked and laughed. He’d already had some health issues and discussed them freely with me. It was a great night for me and, I believe for him. After those many years, we were learning to be friends.

Later, at the thirty-year reunion of “The Amazins,” David came up and gave me a hug. Not one of those quick man hugs but a real hug. He wouldn’t let me go. I hugged him back. I remember standing there in the middle of the floor hugging. Hugging for what seemed like a very long time. That is my favorite memory of my friend David.

Since I heard of his death, I can’t stop thinking of him. I’m proud that we overcame society to be friends.

David will be celebrated for the touchdowns against Alabama, and the great career he had at Auburn. There’s talk that David belongs in the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame. You will get no argument from me on that. But most importantly, I will fondly remember the impact we had on each other’s lives. We are teammates for life, and now beyond.

If work is supposed to be fun, I’m having a ball. For the past year I’ve been working on a project that feeds my soul and in the words of the old Native American Chief in the film Little Big Man “causes my heart to soar like a hawk.” Quiet Courage, a film documentary on my good friend James Owens gets my juices flowing.

James Owens has been my friend since 1970. We were pioneers of college football integration at Auburn University. When we played black players in the Southeastern conference of college football were relegated to one or two per team.

In comparison to James I had it easy. He was the first African American football player in Auburn’s history.

The loneliness, the slurs, the suppression of hurts and emotions stayed with me a long time. It was three decades before I could express it in this manner or any manner. It was many years before I could bring myself to talk about it with my wife and son. Just couldn’t. It was too painful.

But this isn’t about me: Nor about the pain. It’s about my friend and his forty-year relationship with Auburn University.

“I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” James tells me. “I had no idea of the magnitude of being the first black.”

In 1969, James Owens realized a portion of Martin Luther King’s dream. He fulfilled the legacy of Jackie Robinson. He answered prayers of many blacks and some whites in the state of Alabama by answering Auburn’s call to play football at the University. What has followed over the last forty years is a love story.

Not knowing what to do to aid their only black football player and only the second black athlete in Auburn Athletic history, Auburn attempted to treat James as if he was no different than the other athletes. “We treat all our athletes the same” was the philosophy.

Imagine being the only white among a team of blacks. Imagine being the only white in a University of 15,000 blacks where everyone, students, alumni, whites and blacks examine your every move. Imagine there are so few people who look like you on the campus, that your social life consists of sitting in the TV room after games while all your teammates are out partying and enjoying the spoils of victory. Imagine being seventeen and having no family, nearby. Imagine possessing a second rate education, a by-product of segregation that leaves you inadequate in the classroom. Imagine.

Quiet Courage explores these issues and others as told by James, his teammates former coaches and friends. It’s introspective, funny, sad, and full of love. Mistakes were made. James did not graduate. He didn’t play professional football. The University brought him back as a graduate assistant to get his degree. The rules were changed and he was asked to leave. He wandered. Jobs came and went. His wife Gloria who he met when she became one of the few black women at Auburn his senior year, became his salvation.

Then he found the ministry. Saving souls was as tough as scoring against bigotry, but it was more rewarding. His church was only forty miles from where he’d made history, but he didn’t venture close to campus. Nor did the University reach out to him. Love relationships are like that.

Fate intervened. His nephew, Ladarious signed a scholarship to play football at Auburn. James was drawn back to his Alma Mater. This time it was different. Auburn loved him back. Auburn Athletics created the James Owens Award of Courage to honor him. He received his award and a standing ovation in front of 86,00 Auburn fans. Auburn named him an Auburn legend and he was honored at the SEC Legends dinner with other legends from the conference before the 2012 championship game.

Life was good. He was back in the fold. His teammates honored him as the soul of the 10-1, 1972 team known as the Amazins, one of the favored teams in Auburn history.

Then came the diagnosis. His heart was failing. Tears followed. His teammates and the University rallied to his side. Letters, phone calls, and loads of love poured in.

Yes. He realized, they loved him, not only as a football player but, as James Owens, the human being who notched his name in the Auburn history book.

He had one regret. He never received his degree.

The phone call from the Auburn administrators shocked him. The robe, the march, the arena full of the Auburn family, his name called, the honorary degree handed to him, his acceptance speech. He was an Auburn University graduate.

They were back together again, a happy ending. Just like in the movies.

The War Eagle Nation got its due, 22-19. It could have been more. It should have been more but, after so many shoulda, woulda, coulda, almost, damn near but not quite years of great Auburn football, the 2010 version of The Auburn Tigers got er done in early 2011. In the bright lights of the Arizona desert, the boys brought home the crystal football that shines so brightly in the light of a national championship. Auburn Football is the best in the land. No doubt. No more do we have to sing that familiar litany, if only such and such would have so and soed, we would have won, but we’ll get them next year. Never again.

We won it once before. So we’ll behave like it. Coach Ralph Shug Jordan taught those of us lucky enough to be one of “Shug’s boys” to act like a champion, win or lose. He won The National Championship fifty-four years ago, before two generations of today’s Auburn Nation was born. College football’s bright lights didn’t shine as brightly then and the stakes were not quite as high.

Cam, Nick, Michael, Lee, Antoine, Zack, Josh and hero after hero after hero delivered us to the Promise Land of a 21st century National Championship. We’re still drinking from the cup. Cheers to those young men with hearts of champions beating inside them. They reign at the top of the greatest lists of AU football. The teams from 2004, 1993, 1983, 1972, 1957 all have to move over at the top of the pedestal called bragging rights and make a place at the peak for this group. They earned it. Along the way they’ve created new memories for former Auburn players who labored on teams that were on the wrong side of 35-0 scores and promises of wait until next year. Yep, they’re at the top. I’m getting out of the way. Moving over, fast.

This Auburn coaching staff coaches its ass off. They are one of the finest to walk a Jordan Hare sideline. First and ten with the opportunity of a lifetime, they scored and danced in the end zone, the scoreboard of opportunity flashing brilliant high definition color in television sets all over America.

The phone calls and texts began with the final kick, 00:00 on the clock and the Auburn nation inebriated on the elixer of a championship and other worldly juices. Old teammates, cried with joy and professed to me, “I love you.” Ralph who played basketball at Birmingham Southern College, texted “War Eagle Baby.” Terry, my Hollywood actor friend, a native of Oregon, left a voice message, “You guys are the best.” Joe, a writer from Los Angeles, a Texas grad, whose wife died of stomach cancer, last year e-mailed “So happy for you. What a great game.” An anonymous writer texted, “War Damn Eagle.”

Closer to home, my next-door neighborhood an Auburn grad, enthusiastically garbled something inaudible over the Arizona desert cell phone lines, but I got the message. My other next-door neighbor, the Alabama grad, turned off his lights while Auburn celebrated The National Championship in the desert and pretended he could sleep.

The Auburn Nation stands taller today. As football National Champions, (Can you ever say that enough) there will be more scoring opportunities for the University. Academic growth, gifts and donations, business development, and marketing of the University will be ratcheted up. Auburn’s administration with Dr. Jay Gogue calling the plays continues to grow fiscally, academically and internationally. Athletic Director Jay Jacobs guides athletics with class.

The Auburn Nation today is larger, and more relevant on the world stage. We’re here we’re there. We’re everywhere.

Oh yeah. Did I mention we’re the college football national champions?

Let’s do it again!