“Our history is our history.” The statement poured from my mouth as I talked to one of my good friends, an Auburn University alumnus about Auburn University athletic integration pioneers, Henry Harris and James Owens. “Who,” you may ask, as you were not around then, or your memory doesn’t extend back that far.

Let me school you.

First of all, recalling history can sometimes be difficult, especially for those who chose to be on the wrong side of that history. We should never run away from our history. When we do, we can very well repeat it. Maybe in another form or fashion, but we can repeat it. We should also never try to rewrite our history to make it fit the circumstances that make us more comfortable. In loving an institution, such as Auburn, which I do, it is imperative for me to also be objective about it. Our history is our history.

I am not a historian. However, I know what I have lived. I know what I witnessed. I know what I saw others go through. I know how those days of early sports integration made me feel. It’s now been fifty years. Auburn University will honor the feats of these two men with a commemoration during the University’s Annual Black Alumni Weekend.

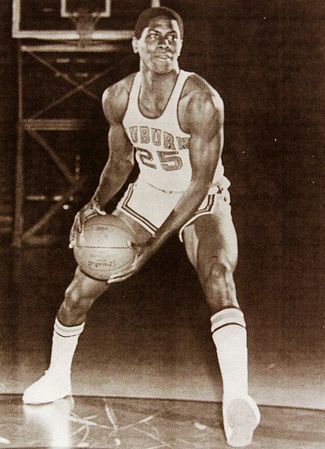

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama was the brave soul who entered first.

Henry broke the color barrier of sports integration at Auburn University in the fall of 1968. It was four years after Auburn University desegregated, due to a court order, by accepting their first and only black student at the time, Harold Franklin. He left three months later.

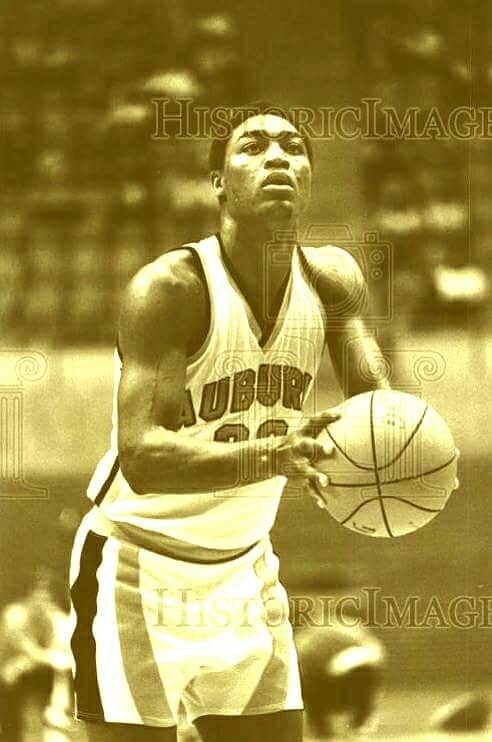

According to Sam Heys author of Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution: A Story of Hope and Self-Sacrifice in America. Henry was not only the first black athlete at Auburn he was also the first black basketball or football player on scholarship at any of the, then seven, SEC colleges in the Deep South.

Heys writes that Henry’s signing was more than a college sports issue. “Historically it is important to remember that the integration of college sports was as much a civil rights issue as it was an athletic issue. College sports were the final citadel of segregation in the Deep South. Within a year of Auburn making the first move by signing Harris, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi State all integrated their football or basketball programs. LSU and Ole Miss followed within two years of Harris coming to Auburn.”

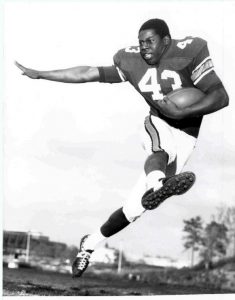

James Owens, from Fairfield, Alabama, walked through the door of sports integration at Auburn next. His chosen sport, football, cast an even brighter spotlight on his integration effort. James often confided to me, that without Henry, he would have left. James said, “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I thought it would be about playing football where I had excelled all my life but this was more than that. I had to be more than a football player. Everything I did was monitored and watched. I was a hero to the blacks. I was a mystery to the whites.”

In 1968, Auburn essentially became the leader in moving toward equality and justice in the Deep South. Sam Heys writes, “Auburn should be proud of the leadership position it took in signing Henry Harris to a basketball scholarship.” Does that mean that Auburn did everything right? NO! There were plenty of rough patches. It does however highlight Auburn’s willingness to step forward before any of their brethren. It also means Henry and James were willing to take that step along with the University. The University, Henry and James became willing leaders in this great cultural experiment.

Did these men have great careers? On the field they were good. They were leaders, not superstars.

Statistically, Henry averaged 12 points 7 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game. He made third team All-SEC after the ‘71-‘72 season.

In the ‘71 and ‘72 seasons, James averaged 5.1 yards from scrimmage, 29 yards on kick returns, 10 yards on pass receptions and 4.1 yards rushing. Not bad considering the few times he got his hands on the ball.

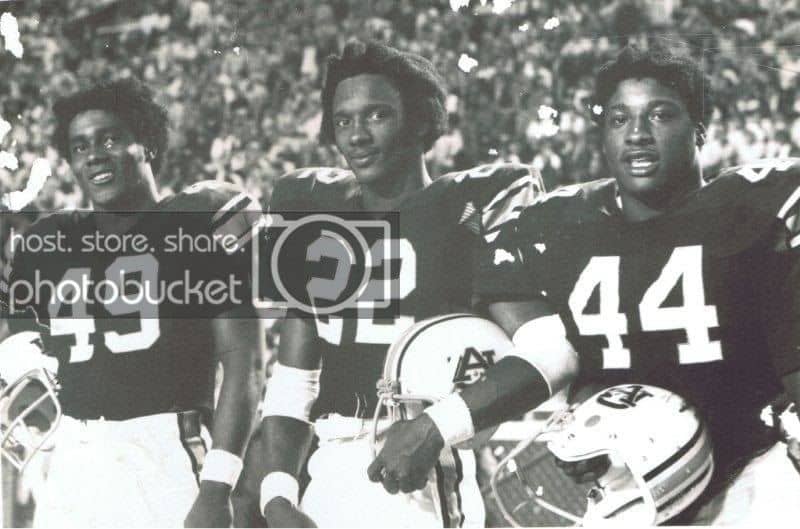

But far more important than their statistics, they led the way. They led their teams and inspired others, including me. They represented the University well. They sacrificed for others. They opened the floodgates. Personally, they became my big brothers when I joined them at Auburn in 1970.

I witnessed their feats on the basketball court and the football field. I also witnessed their hardships, their loneliness, their courage and their despair. While I was at Auburn, Henry never had a roommate. James and I lived together his last year.

These men may never be in any Sports Hall of Fame. They should be! Does changing a segregated way of life compare with running a touchdown or grabbing a rebound? Are you kidding? Is there any comparison? I know my answer. They may never be included with the outstanding athletes whose names are carved in cement on the streets of downtown Auburn or whose busts are included in the SEC Hall of Fame. But they belong there. Plain and simple, they belong there.

The simple question sent my mind reeling backward through time to those hot, hot, muggy oppressive days of summer. The question was from a neighbor commenting on how hot and uncomfortable the month of July has been. Temperatures have resided in the mid 90s with the heat index well into the 100s.

Ours is a walking, jogging, bike riding neighborhood. People stand in the yard and talk to each other. These days you can do that early morning and late evening but during the middle of the day the heat has been too much. My neighbors question sent my mind back to the heat of yesteryear.

“How did you all stand practicing outdoors in this hot sun? I can’t imagine,” was the question?

I answered immediately, “I don’t know. Sometime I ask myself that question.”

Looking back to the 1970s, it was always brutally hot in Auburn, Alabama in July and August. For clarification, it’s brutally hot in Auburn most summers. But for that five-year period, I was practicing with the football team in the steamy hot sun, with no breeze and only the occasional water break.

Walking on, I had to prove I deserved a scholarship. I did. I had to earn a starters job. I did. I had to keep that job for three years and help us win games and national rankings. I did that too. Standing in the hot sun with my neighbor, I felt a trickle of sweat run across my brow and down my face. Looking back on it now, in a six-decade old body, I wonder how we did it as well.

You see it was about more than being a big man on campus, the glamour of television, or signing autographs. Those were the byproducts, the benefits of hard, grueling, day-to-day grinding work in summer camp. Since school had not started we could devote all our time to practice. Summer camp could make or break our season.

We were young and frisky like colts. Reporting to camp we went at it twice a day for two full weeks before we tapered off to a regular practice schedule. The heat was unbearable. But we were on a mission. We went out in the morning in full pads. We hit, we hit and we hit some more.

In the afternoon practice we did it all over again. Dripping wet with sweat, our pads and practice uniforms now weighed close to ten pounds more as they were soaked. There was no Gatorade. There were no water coolers. It was according to our coaches, “How bad do you want it?”

We did get the occasional water break! People laugh when I tell them we had a water spigot about six inches off the ground that we had to kneel down to slurp its precious cold water on our two water breaks a day. It was yesteryear when the hardship of making a football team was equated with your manhood. “Prove you’re a man,” was the message we were given. If that was what it took to be a man we were willing.

My mom feared for me because I could not hold my weight in that hot sun, running miles and miles a day. I assured her I was okay.

Between practices we stuffed ourselves with food. Caught a quick nap and headed back out for the afternoon practice. Before dressing out we would check the afternoon depth chart. Had anybody moved up on the roster? Had I moved up on the roster?

Inevitably we reached that point in practice where attrition would take hold and those who refused to do it any longer would pack their bags and ease out of their dorm room under the cover of darkness and sneak off to another life. Putting that experience in their rear view mirror. We didn’t hold it against them. Maybe it took more courage to leave than it did to stay.

Was it worth it? Yes! Would I do it again? Yes! Absolutely. Could I do it again at this stage? Absolutely not!

As I explained to my neighbor what that part of my life was like, I smiled as I remembered the angry screams from coaches, the camaraderie we built, the games we won, “the teammates for life” tag we have placed on ourselves. The stories we now tell. All because of that “torture” we underwent in that brutal oppressive heat.

“I don’t see how you all did it,” my neighbor exclaimed.

With youthful exuberance and a big smile, the words shot from my mouth, “It was fun.”

It was August 2011! I’ll never forget counting down the days until I left. It was so sad…but it was so exciting, so major, I couldn’t wait for the day. I said my “proper goodbyes” to most of my friends. That morning I hugged my mom and my Nana, and dad and I got in my packed down car and started our 765 mile road trip to a place where I had only been once, and didn’t know a soul.

After ~about~ 12 hours in the car, dad and I made it to our hotel. I remember coming off the exit and seeing a Golden Corral (ugh! Haha), a WalMart, and then getting to the Jameson Inn. We had made it to Auburn, Alabama. This was my new home. Hungry, we asked where we should eat…the recommendation…Niffer’s! We got fried pickles and I signed the wall somewhere near the bar. After we ate, we went back to the hotel and settled in for the night. At some point, one of us made a comment about the TV, or clock, or cell phones or something being a different time. Without thinking I said, “well maybe we’re in a different time zone,” and after a few seconds, we realized we were! (lol)

Auburn had just won the National Championship in January, and you couldn’t drive by, or walk in, anywhere without the store, signs along the road, or the items in every store letting you know. I watched the game with a group of friends after attending a Fort Hill basketball game (I think?). When it was getting down to the end, we joked that whichever school won is where I would go to college. That’s not the reason I went to Auburn, but isn’t that funny?

I moved into my apartment, started my classes, made a few friends, and quickly got a job. I got hired at the Sonic on South College. It lasted less than a week. Turns out an unorganized store and $4.14 an hour wasn’t for me. I called and quit the Friday before the first Auburn game.

On September 3rd, Utah State came to Jordan-Hare. All I could do was take it all in. RVs full of people tailgating, cars parked all over the place, and people in orange (and some blue) were everywhere. It was an “All Orange” game, so I wore my new orange Auburn shirt. I climbed all the way to the top of the stadium, and for the first time- I saw the Eagle fly, listened & participated in the stadium-wide Auburn call cheers, and watched the marching band in awe. If you ever go to an Auburn game, DO NOT miss pregame, it’s the best part!

The Auburn Marching Band during pre-game.

The game went on, and boy, if that first game wasn’t a perfect metaphor for my new life as an Auburn fan. I’ve learned to hope for the best and expect anything. We beat Utah State 42-38, and I went out and bought myself a pair of orange Chuck Taylors in celebration.

Who knew I’d ever own this much orange?

Even though I didn’t know it yet, the “Auburn Family” was a real thing. My Auburn Family welcomed me, an outsider, and taught me all the things I needed to know. They welcomed me to their tailgates, they invited me to games with them, they taught me the cheers, the songs, the traditions, and they showed me what a real Auburn fan was.

I can’t believe that was seven years ago. There were so many new experiences and so many changes I have experienced since then. But as we prepare for another football season, I look back at those milestone moments as a Auburn student and fan.

(As published on westernjournalism.com, Sept. 28, 2017)

I saw him last spring in Montgomery, Alabama. I was there to speak to a Leadership Montgomery group. As I looked out over the crowd, he sat there, grinning. Grinning at me! Grinning as if he had a secret no one else in the room knew. As it turns out he did. It wasn’t until a few weeks ago, we found the time to get together and talk about it.

The story travels back into not only my past, but also, our mutual history. Back into a time I call yesteryear. Memories fade. Details get fuzzy but the essence of the story, he remembers in full.

We were freshmen at Auburn University. We had at least one class together. We obviously struck up a relationship.

Sam Johnson tells it like this. We both started Auburn in fall 1970. As freshmen we were coming at the early integration of the University from different perspectives. Sam is white. He chose to get to know me. Not just in class and not just as an athlete. Sam chose to befriend me and get to know me in a time when not many on the white side of the integration experiment at Auburn chose to cross over to that other side. He could have chosen to avoid the integration debacle. It wasn’t his fight. He was secure socially in a fraternity and had the advantage of not being the first in his family to venture to Auburn. I was at the other end of that spectrum.

When we met this September, Sam remembers, that we talked a lot in those days; or rather I talked… a lot. Sam says I was angry and voiced my anger to him about the experience between classes while sitting outside of The Haley Center building. Some of that is fuzzy for me but I don’t doubt I was angry. I do wonder about my sharing my feelings with him. That was something I did not do with people I did not know well. It was part of my anger. Integration was lonely, boring, demeaning and more like the drudgery of a miserable mission than a fun education experience. Today when I hear my fellow white alums from that era or teammates tell stories of their college days, I wonder if we went to the same University. The few of us black students who ventured into integration during that time were pioneers on a mission to make things better for those who would follow. Was it fun for us? Nope. The black athletes, at that time there were three of us in the Auburn athletic department (1basketball, 2 football), were the forerunners to today’s games, but we were not the beneficiaries of our efforts. I kept who I was and what I was thinking bottled up inside. My insides were tied up in knots, knots of anger. I often kidded some of my white teammates telling them, “If you knew what I was thinking, you’d be scared of me.” Sam must not have been afraid. Because according to Sam, I let him in.

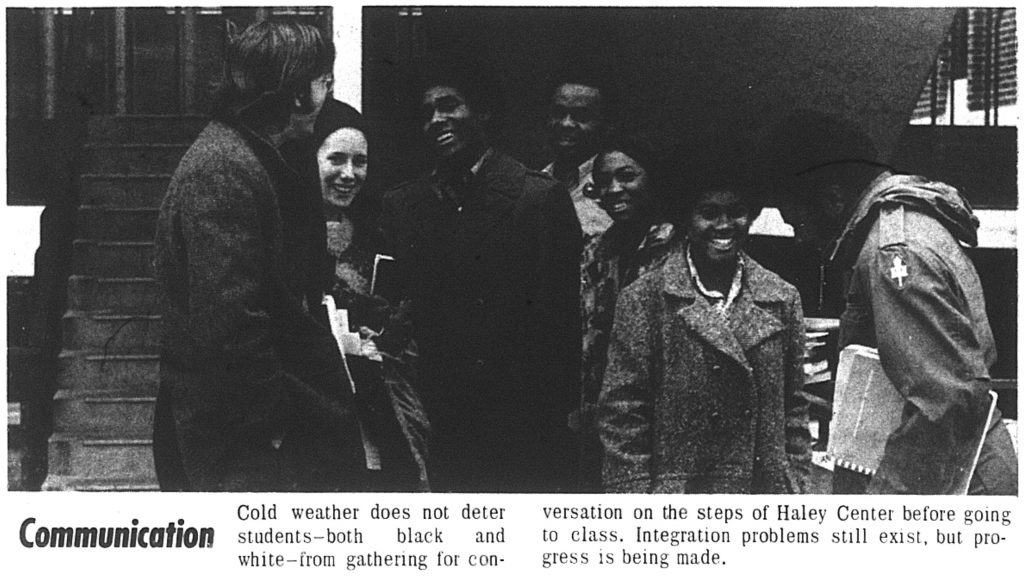

The visible proof of our relationship appeared in the school newspaper, The Plainsman that I would later write for. The paper ran an article on race relations on campus, with an accompanying photo. Sam brought a copy of the photo to our meeting in September. The photo was of Sam and a white female, two other black males: Joe Nathan Allen and Rufus Felton, two black females who I do not remember, and me. We were all smiling. We had been recruited to pose for the picture. Someone walked up to Sam and me and asked if we would pose. Someone else recruited the others. We agreed and met the others on the steps outside Haley Center. In the photo we were all smiling like friends. Sam did not know any of the others, just me.

The cut line under the photo in The Plainsman read, Communication. Cold weather does not deter students both black and white from gathering for conversation on the steps of Haley Center before going to class. Integration problems still exist but progress is being made.

The photo is dated February 12, 1971.

Sam caught hell from some of his fraternity brothers and others for being in the photo with five black students. But he went even further. Because of my venting, Sam took it upon himself to go to the University recruiting office and tell the officials what I had said. Not telling on me but repeating the things that I had said needed to be done to make progress at the University. At first he was given the run around but they eventually listened. Auburn administrators even went so far as to put some things in place to recruit more black students and improve the social atmosphere.

Before we left our September meeting, Sam says that I inspired the little progress that was made in those days. I thank him but know that it was in part, credited to him. I could not have gone and done what he did. I would have been viewed as the angry radical in the administrator’s eyes. I could have lost my spot on the team, lost my scholarship, gotten kicked out of school. On the other hand, Sam would not have known what to say if he had not listened to me. When Sam took it to the administrators it became a university problem not just the angry black guy’s problem. He did what I couldn’t do. It takes us all. Sam taught me that. Thanks Sam!

Alfre Woodward, the talented actress says to me, “I’ve got someone I want you to meet.”

“Okay,” I agreed.

She led me to a corner seat in the rented party room at the Santa Monica, California Airport. The party was for her husband’s birthday. The room was a who’s who of Hollywood stars having a good time outside the bright lights.

As soon as I saw the guy she wanted me to meet I told her, “I know this guy.” Of course I knew him. He was the secret service agent guarding the President every week on the hit TV show The West Wing.

But… there was something else. I actually knew this guy. He knew me as well. We excitedly shook hands. Alfre said, “I believe you are both from Alabama.”

That was true. He’s from Montgomery. I’m from Birmingham.

But, we’re more than that.

We immediately recognized each other because we’d both gone to Auburn University during the same time period. We had not been close friends, not even close acquaintances. We knew of each other the way you know of someone who has achieved some notoriety on a campus of 20,000 students. He had been involved in student government and his fraternity. I’d played football and written for the school paper.

It didn’t take us long to reacquaint. We soon got together for dinner with our wives and we’ve been fast friends ever since.

Michael O’Neill, “Michael O” I call him, is a professional actor. He knows his business. His IMDb page proves that. He has worked in more than 75 episodes of television and 30 films. Michael O has worked in New York, Los Angeles and across Canada. He’s worked with Alfre Woodard of course, Halley Berry, Martin Sheen, Clint Eastwood, Robert Duvall, and a host of others. Everyone except…

We often say between the two of us we have nearly 50-years of combined experience, more than 115 episodes of television and nearly 40 films. We have worked ER, Cold Case, Without A Trace, Boston Legal, Close To Home, The West Wing, NYPD Blue and Chicago Hope. But never had we worked together, until 2016.

Our Alma Mater, Auburn University, and the whole Auburn Nation was deeply involved in a $1 Billion Fundraising campaign. Michael O, I and others were asked to host, MC and dramatize a live 90 minute show in support of the campaign in Dallas, Houston, Tampa, Atlanta, Birmingham, Nashville, New York, and Washington D.C. We relished the opportunity to work together and to support our Alma Mater.

I caught up with him by phone for this post and it was like old times.

TG: Where are you?

Michael O: Working on a film in Memphis. Where are you?

TG: In Florida. I’m home for the next five days and then off again.

Michael O: Five days sounds like a vacation.

TG: Caught a break. I’m in and out the next three weeks.

TG: I have to ask you; we got to work together on the Auburn Campaign Events. What did it mean to you?

Michael O: It’s nice to give something back. It’s what you hope a college education can do. It reflects further than we could imagine. It’s easy to participate because I believe so strongly in the Performing Arts Center (coming to campus) and not just because you and I are in the arts but also because it’s important to our students and their interest, their outlook and their experience as they go out to shape the world.

TG: Talk about the night Alfre introduced us.

Michael O: That was funny! I remember my daughter Ella was 5-6 weeks old. It was the first time my wife, Mary and I had been out in a long time. We wanted to get out.

I had just worked on a project with Alfre, “The Gun in Betty Lou’s Handbag.” We had so much fun working together.

TG: She’s great. (TG worked with Ms. Woodard on Miss Evers’ Boys).

Michael O: That night in Santa Monica she told me, “I got somebody you got to meet.” She walked up with you and right away I said ‘I know him. We were in school together.’ I knew of you from campus, not just from playing football.

TG: That’s funny I told her the same thing. I know him. That turned out to be a special night.

Michael O: Yep.

TG: Talk about your current project.

Michael O: It’s set in Iraq. A young man goes off to war, gets thrown in the middle of everything and comes back with PTDS. He loses his faith and family. There is a very spiritual message to it. I play his mentor. Military guy.

TG:Do you get immersed in your characters? How far have your gone with this guy you’re playing?

Michael O: I’ve done so many films playing military guys and know quite a few guys. I consider it an honor. They help me with the research. I try to be very respectful. It has to be believable. I tell them, ‘don’t let me get caught acting.’

TG: Of all the projects you’ve done, what’s your favorite character and why?

Michael O: Mr. Pollard in“SeaBiscuit.”One of the first times I’ve wanted something so badly and got it. I blew it wide open in the audition. There were a lot of guys high above me in the food chain who were in line for that job, but they chose me in the audition. The character was actually written better in the film than in the book.

TG: I often like to say the profession is like being a migrant worker. Here today, on to the next gig tomorrow.

Michael O: I’ve worked in so many places. That’s been part of the cultural education. Off the top of my head let’s see what I can name. New York and Toronto several times, Based in LA, so all up and down California; Santa Fe, Salt Lake City, Atlanta, New Orleans, El Paso, all over Texas; Fort Davis Texas, Alpine Texas, Houston, and Austin. Umm, Lexington, Kentucky, Florida, London…

TG: I want you to tell me the Sully story; but first talk about being recognized on the street.

Michael O: (Laughter!) Will Geer (“The Walton’s” and “Jeremiah Johnson”) mentored me. He taught me that it’s more important to be interested in the other person rather than yourself. You have to want to give back to them. You’re sharing an experience with them. It feeds me as much as it does them. Whenever someone recognizes me on the street, my daughters(3) will always bring me back to earth. They roll their eyes at the fact I’m talking to someone I don’t know.

It’s always cool when we’re both together and someone recognizes the both of us.

TG:Yeah that’s always fun!

TG: Tell the Sully story.

Michael O: I’m riding down this elevatorand this guy is stealing glances at me. When the door opens before he gets out, he says, ‘You did a good job, landing that plane on the Hudson River.’ I responded, Thank you!

TG: Any of your girls following in your footsteps?

Michael O: Nope: They’ll find their own way.

TG: What advice do you give to those who ask you about becoming an actor?

Michael O: I tell them, especially if they are asking for their children. I tell them regardless of how far their child goes in the business or if they even get into the actual business part of it; it teaches you so much. Creativity, to run your own business, listening, collaborate with others, teaches you to be observant, teaches you to be in life’s light when it’s your turn and to not be when it’s not.

TG: We still going to do a show together?

Michael O: You bet!

The immediate utterance of “Oh No” spilled from my mouth when first hearing the news of Wayne’s death. It was not long after that I began to smile, and continue to do so when I think of Wayne “Baltimore” Bracy. Baltimore left us on March 21.

The blogs and postings I’ve read by others speak of a Wayne I did not know, the life he lived after leaving Auburn University. Apparently, he was a dynamic high school basketball coach, for 20 years. He took his team, Deshler High School on five trips to the High School Final Four during his final six years with the team. He was described as very intense and passionate about his coaching. Those who know this part of his life say he was a mentor to a lot of young men and young ladies. All of that sounds like him from earlier days.

I met Wayne in 1974 at Auburn University where he signed to play basketball. Wayne joined a team of stars, two of which, Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell, went on to be stars in the NBA.

1974 was a watershed year for Auburn University and black athletes. In 1970, when I started at Auburn, there were only three black athletes between the football and basketball programs. By 1974, there were 14 black athletes between football, basketball, and the track team. As Sam Cooke sang, “A change gon’ come,” and it was on the way.

Being a senior during Baltimore’s freshman year, I got to know him and acted as a guide - particularly to the young players who were in their first integration experience. Coming from an all-black environment to a nearly all-white one was an adjustment some could not make. Baltimore was a good student; he made the transition.

During that time, so many basketball stars were signed that it was inevitable someone would have to step aside for others, or adjust their role for others to play. Baltimore would not become a big basketball star scoring-wise, with Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell scoring 20 and 18 points respectively and Gary Redding scoring nearly 15. For his career Wayne scored 4 points per game, but he was a contributor, a standout. Some guys become standouts because they can set one role aside and move into another.

Wayne’s role changed. He was a fundamentally sound player who learned from the legendary coach Willie Scoggins at Hayes High School in Birmingham. His strength was guiding the team from the point. Much like Magic Johnson, Wayne could impact the game without scoring. He became a defensive stopper. The other team’s best scorer? Give him to Baltimore. He’d shut him down.

“I have a style all my own,” he told me, referring to his style on the court and how he dressed off-court also. He was stylishly dressed as he walked to class, journeying into his new world. He named himself Baltimore. As long as I knew Wayne that’s what I called him.

As a senior, I tried to have a special relationship with the freshmen. Baltimore and I developed one. I admired the way he carried himself. He had an impact on me.

He was studious, strong, and lived life the way he played defense…man-to-man. Baltimore made an impression on me that has lasted more than 40 years. That’s quite an impression when you consider I haven’t seen him in nearly 20.

On a Friday night, before a Saturday Auburn football game, at the busy, crowded Auburn Hotel and Conference Center, I heard my name called as I entered the lounge. “Hey Thom, come on over here and sit down.” It was a command as much as a request. Charles Barkley was parked in a corner holding court with several guys sitting around him, including another Auburn basketball Legend, Chuck Person, “The Rifleman,” who is now on the Auburn basketball staff. My friend Mychal and I joined them and let’s just say it was a memorable evening.

Charles held court, a king on his throne as he sat with his back to the wall able to see all who entered his domain. For the next couple of hours our laughter rocked the lounge as we cracked jokes at each other’s expense, expounded on sports and politics, enjoyed several beers and pizzas, and of course listened to Charles.

In a crack aimed at me he blurted out to a nearby waitress, “Yeah, I’m out with my Grandfather tonight.” Everybody got a big laugh at my expense. It was that kind of night.

Charles loves Auburn and its people and proved it by posing for at least 50 pictures that night with whomever came forward to ask, children, men, women, past acquaintances and anyone who wandered into the room, discovered that Big Charles was in the house and wanted a photo. Often they would interrupt our conversations, yet Charles was always gracious and we would make room for the person to enter our little domain and get the photo op. I admire his graciousness. He made all who asked feel special.

Charles was in town for the game but also for the announcement that Auburn athletics would honor him with a statue in front of the basketball arena much like the statues of Heisman Trophy winners Bo Jackson, Pat Sullivan and Cam Newton grace the outside of the football stadium. The weekend also included the Bruce (Pearl) and Barkley golf tournament played that Monday with some 120 golfers competing from around the area in support of Auburn basketball.

In typical Charles fashion he asked that his statue be made from a younger picture of him when, as he termed it, “I was skinny.”

“Must be a baby picture,” one of the guys quipped.

The laughter rocked the lounge.

The fun continued throughout the evening.

“I was the leading rebounder in the SEC, when I played with Chuck (Person).” We waited for the punch line. Charles delivered. “Hell it was the only way I could get a shot. Chuck would put it up, baby.”

Chuck could only laugh.

I met Charles for the first time a few years ago. We were both speaking at a conference in Montgomery. I approached him and extended my hand to shake and he put me in a bear hug and held on to me all the while saying “Thank you.”

Puzzled I asked, “For what?”

“You know what you did,” he responded.

“You and the first brothers to come to Auburn made it possible for us.” He responded, referring to the integration of Auburn sports in the late 1960s and early 1970s and those athletes like himself who came behind us early pioneers.

“Thank you.” He said again.

I’ve never forgotten that and never will. That recognition is as important to me as any statue could ever be.

Since then we have been friends, comfortable enough for him to crack me about being his grandfather.

After a couple of hours we drifted up the street to another bar restaurant in downtown Auburn. With Chuck Person having left because of an early morning basketball practice five of us headed up the sidewalk. Heads turned as Charles led the way. A couple of people stopped me to shake hands and relay an Auburn anecdote.

“Hey Charles,” I called out to him as we walked up College Street. “Yeah?” he answered. “Look at all these people looking at us,” I began. I waited until I had all the guy’s attention and then stated. “They’re trying to figure out who the big guy is walking with Thom.” The guys laughed, especially Charles.

As the evening wound down, Charles and a couple of the others decided they would check out another spot before heading back to the hotel. I begged off. Charles couldn’t resist. “Yeah, I know your wife,” he laughed. “Better get on home before you get a whipping.”

I hugged him. It had been a great evening.

I met the champ, Muhammad Ali, in 1973. I met him at Auburn University. He was on campus for a lecture entitled “The Intoxications of Life.”

As a part of our Journalism class, the professor arranged for students to cover Ali’s press conference. It was being held in the same building our class was in, Haley Center. Excitedly, we packed up our belongings and headed downstairs to see the champ.

I have been a Muhammad Ali junkie since 1964, when I was twelve years old and he beat Sonny Liston in Miami. A young potential athlete, I invested my time and attention on athletes who had a social conscience, who wanted to make a difference, who had something to say and who often became controversial if they chose to speak about human rights. Ali had something to say and the boxing ring could not contain him.

He changed his name from Cassius Clay, his given name, to Muhammad Ali, which he said meant, “worthy of all praise most high.” He upset the boxing world by beating the “Big Bad Bear” Sonny Liston. He became a Muslim minister. He declared himself the greatest heavyweight champ of all time, which did not set well with the previous generation. He shook up the world with, “Just take me to jail.” As a conscientious-objector, he refused to serve in the US Army after being suspiciously reclassified 1A. He had originally been disqualified for military service. Ali said that he would not fight the Vietcong, and was stripped of his title.

Ali lectured on college campuses across America. Gave people hope that they could have better lives. He became a different symbol of courage. Eventually the US Supreme Court unanimously reversed a lower court decision and granted Ali his conscientious-objector status. He came back to boxing and lost for the first time to his rival Smoking Joe Frazier, (a fight I saw closed-circuit in Columbus, Georgia). He lost to Ken Norton (saw that one too), who had broken his jaw. Now, he was in Auburn, just a few feet in front of me.

I sat there with my reporter’s pad and pen. I was in heaven.

The champ spoke about the “Intoxications of Life.” Ali talked about humbling himself after his two defeats, which he attributed to his immersion into life’s intoxications; too much money, too many women, long nights, not enough training, and not enough godly living. It seemed a perfect message for those of us from the past year’s football team. We had finished the season 6-6 after two seasons of 9-2 and 10-1. Perhaps we had gotten too full of ourselves as well.

After the press conference, Ali put on a show at my expense in the lobby of the auditorium. The photo captured by university photographer Les King, hangs on a wall in our home. The champ has a playful but serious look on his face as he squares off in perfect boxing form shouting at me, “JOE FRAZIER, JOE FRAZIER.” My hands are up in a defensive pose. My fists are not balled up and I am laughing really hard. I too am wary though. He was incredible fast. I dared not make a false move. Afterward, I was interviewed and asked what it was like to square off with the champ.

Our paths would somewhat cross again 22 years later when I performed the one man play “Ali” in my hometown of Birmingham, Alabama. I sought out the script and director, then played the champ as a young man who would morph into the older version of himself as he was beginning to struggle with the same Parkinson’s disease that eventually KO’d him. I prepped like an athlete. I researched Parkinson’s, watched film, read magazines, hit the heavy bag, listened to tapes of his voice, studied his walk, and trained… and trained. For the run of that show, to the audience, I was Muhammad Ali.

I still have the robe. Identical to the white one he wore in the ring with his name on the back in big red letters. I still have all the research materials, including the 1971 Life Magazine issue with Ali and Joe Frazier on the cover with photos from the epic fight taken by Frank Sinatra.

In his own words, Muhammad was the greatest boxer of all time. In the play he asks, “Do you know what it’s like to be the best in the world at something? The best in the world?”

He became more than a boxer. To many he was a symbol of hope. Also, in the play he says, “I could knock on anybody’s door in the world and they would invite me in.”

“I shook up the world,” he concluded.

Yes he did.

The Big O is gone.

My friend. My teammate. The man who helped me through the biggest cultural change of my life is gone. James Curtis Owens died today, March 26, 2016. I knew it was coming. We all knew it was coming. But knowing and living beyond it leaves a hurt and pain deep down in my soul.

I first saw the Big O on a Friday night at John Carroll Athletic Field on Montclair Road in Birmingham, Alabama. I was a junior at John Carroll High School, playing my first full year of organized football. We were a small, rag tag, undersized bunch playing about two classifications above our ability and size level. We didn’t win very often.

The opponent was Fairfield High School. They were good. They had a starter named James Owens, who would later sign with Auburn University, becoming the first African American to integrate a major state university in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi… the Deep South. Now, he was warming up across the field from me. A running back, he was tall, lanky and wore a horse collar around his neck. He was about 6’2” and weighed close to 210 pounds. He looked dangerous. Ready to kick some you know what!

Our coach had warned us about him. He’d then gone on to tell the lie that coaches tell outmanned teams when they are about to get slaughtered by a bigger, faster, better team with bigger, faster, better players.

Referring to Owens, our coach said, “Hey! He’s no better than you. He puts his pants on one leg at a time just like you do.”

We all knew that was bullshit. Putting his pants on like we did had nothing to do with playing the way we did. This guy was All-State in football and track. He ran the 100 hundred-yard dash and threw the shot-put. He was a monster. I was glad as hell I wasn’t on defense.

It wasn’t pretty. He left carnage on the field. I don’t remember the score but it wasn’t close. After it was over, I watched him walk off the field where he had dominated us. Having integrated Fairfield High School football he was now heading off to be one of the first blacks in the Southeastern Conference.

Two years later, I would join James and Virgil Pearson, also from Fairfield, and Auburn’s first African American Athlete, Henry Harris, at Auburn University.

As a basketball player, Henry often travelled in different circles. For Virgil and me, James became our Daddy. We nicknamed him “Daddy O.” He was strong like our fathers, but gentle towards us, who had followed him. We not only respected him, everybody, on and off the field and in the athletic complex, held James in high esteem. Integration made things socially awkward but everybody respected James for his quiet, dignified courage. That respect lasted all of his life.

Our special friendship lasted from 1970 until his death. Like close friends we drifted apart throughout the seasons of our lives but we always found each other again because of the love and respect we had for our shared experience.

Henry left Auburn University after his senior basketball season. Virgil left his sophomore year, looking for a different experience. For the next two years on the varsity football team It was just James and me, as athletes of color. For the rest of his life we always relived that experience.

Between us we realized there was no one else in the world who shared that loneliness, that moment in our lives where we carried the pail of integration uphill without much assistance from those who could have helped us along. Those times were about providing for those whom would follow. We knew that. It kept us going.

James kept me grounded. He talked me down many times when, emotionally, I was way over the top. Over time, we embraced our teammates and they embraced us with that special bond that comes from the shared experiences of being teammates and winning games. During the two years when James and I were the two black pioneers on the team, we won 19 games and lost 3. We were a part of something bigger than us.

Throughout the decades that followed we talked a lot about those times. We always circled back to that experience. What had been a painful part of our lives had become, by the 21st century, a memory of achievement, a gift that we gave to all who followed at our university, not just the black athletes. We also grew to love our teammates and they loved us back. Today we are teammates for life. It ‘s more than a slogan. We live it.

James is an Auburn University icon. He doesn’t need for me to tell everyone about his contributions. Look around the university and you will see his accomplishments in the faces of the young men on the football team, the basketball team, the track team, the baseball team and in the faces of the young women on the softball team, the basketball team and all the other sports that did not exist before integration.

He will always be remembered for what he gave to Auburn University, the state of Alabama and college football. I will always remember him as my friend.

Laura Nall & her little sister at an Auburn football game.

3/1/2016

The Young Women’s Leadership Program (YWLP) is a curriculum-based, after school mentor program which pairs young women from Auburn University and young women from Auburn Junior High School. “Through YWLP, the mentors and mentees (also referred to as Big and Little Sisters) will develop leadership and relationship skills that are vital to maintaining a healthy lifestyle. This program provides an opportunity for teen girls to become more educated and aware of their personal values and goals,” according to the website.

Emily Hedrick & her little sister posing with their painted pumpkins for Halloween.

YWLP came to Auburn in 2010 and is modeled after the University of Virginia YWLP which was founded in 1997. YWLP is a nationwide organization dedicated to facilitating the empowerment and autonomy of young school girls. It provides both one-on-one mentoring and structured group activities. Each week bigs attend a one hour human development and family science class about adolescence taught by Dr. Donna Sollie then have an hour meeting with their small group of other bigs. Bigs and littles are paired up at the beginning of the fall semester based on compatibility, after a “speed date.” Every week there is an on-site meeting at AJHS where small groups of about six pairs meet. Here the group goes over a lesson, connects the lesson with real-world situations and have fun playing games. Beyond the class and on-site meeting, pairs are required to spend one hour of one-on-one time each week. “My little sister and I went to an Auburn football game in the fall, and that is definitely my favorite thing we've done together,” said Laura Nall, a big in YWLP.

YWLP is beneficial to both bigs and littles. For bigs, you are not only teaching important lessons and skills, but also learning them on the way. Lydia Purcell, a YWLP big sister says, “I have learned how to be more understanding and how to thoroughly listen. Being in a place of leadership like that is intimidating but rewarding.” The mentor program exposes bigs to leadership and friendship roles, the importance of daily choices, knowledge and acceptance of others different from themselves, and a way to give back to the community while still learning and earning college credit!

Lydia Purcell & her little sister on an ice cream outing.

YWLP is open to all female students at Auburn University interested in impacting a life and furthering their leadership experience. YWLP is a two-semester commitment from August to May. The fall semester counts as three credits and the spring semester counts for two. “YWLP is an incredibly rewarding and character-shaping experience, but it can also be challenging. If you want to broaden and deepen your perspectives, develop meaningful relationships with your peers, and have the opportunity to positively impact a younger girl's life then this is the program for you!” said Megan Swanson, a current YWLP big sister. Applications are now being accepted for the 2016-2017 school year. Applications are due by April 8 and can be found online at http://goo.gl/forms/khN0a6o5mr . If you have any questions, please contact The Women’s Resource Center 334-844-4399 or email graduate assistant Lindsey Henson at lnh0010@auburn.edu.