The immediate utterance of “Oh No” spilled from my mouth when first hearing the news of Wayne’s death. It was not long after that I began to smile, and continue to do so when I think of Wayne “Baltimore” Bracy. Baltimore left us on March 21.

The blogs and postings I’ve read by others speak of a Wayne I did not know, the life he lived after leaving Auburn University. Apparently, he was a dynamic high school basketball coach, for 20 years. He took his team, Deshler High School on five trips to the High School Final Four during his final six years with the team. He was described as very intense and passionate about his coaching. Those who know this part of his life say he was a mentor to a lot of young men and young ladies. All of that sounds like him from earlier days.

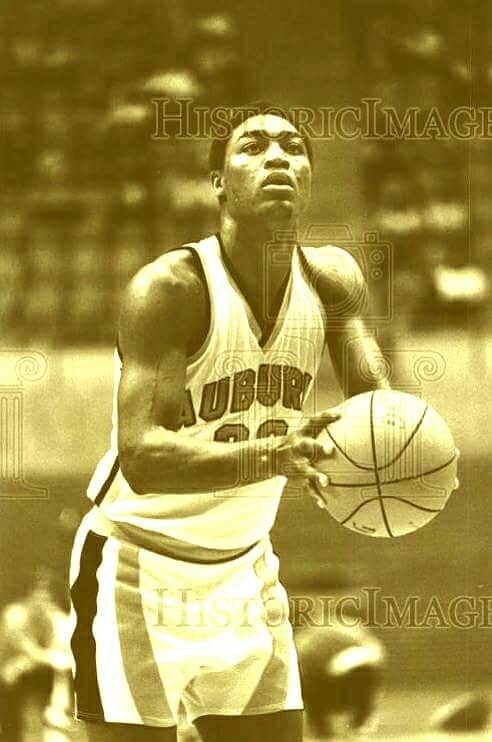

I met Wayne in 1974 at Auburn University where he signed to play basketball. Wayne joined a team of stars, two of which, Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell, went on to be stars in the NBA.

1974 was a watershed year for Auburn University and black athletes. In 1970, when I started at Auburn, there were only three black athletes between the football and basketball programs. By 1974, there were 14 black athletes between football, basketball, and the track team. As Sam Cooke sang, “A change gon’ come,” and it was on the way.

Being a senior during Baltimore’s freshman year, I got to know him and acted as a guide - particularly to the young players who were in their first integration experience. Coming from an all-black environment to a nearly all-white one was an adjustment some could not make. Baltimore was a good student; he made the transition.

During that time, so many basketball stars were signed that it was inevitable someone would have to step aside for others, or adjust their role for others to play. Baltimore would not become a big basketball star scoring-wise, with Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell scoring 20 and 18 points respectively and Gary Redding scoring nearly 15. For his career Wayne scored 4 points per game, but he was a contributor, a standout. Some guys become standouts because they can set one role aside and move into another.

Wayne’s role changed. He was a fundamentally sound player who learned from the legendary coach Willie Scoggins at Hayes High School in Birmingham. His strength was guiding the team from the point. Much like Magic Johnson, Wayne could impact the game without scoring. He became a defensive stopper. The other team’s best scorer? Give him to Baltimore. He’d shut him down.

“I have a style all my own,” he told me, referring to his style on the court and how he dressed off-court also. He was stylishly dressed as he walked to class, journeying into his new world. He named himself Baltimore. As long as I knew Wayne that’s what I called him.

As a senior, I tried to have a special relationship with the freshmen. Baltimore and I developed one. I admired the way he carried himself. He had an impact on me.

He was studious, strong, and lived life the way he played defense…man-to-man. Baltimore made an impression on me that has lasted more than 40 years. That’s quite an impression when you consider I haven’t seen him in nearly 20.

The Big O is gone.

My friend. My teammate. The man who helped me through the biggest cultural change of my life is gone. James Curtis Owens died today, March 26, 2016. I knew it was coming. We all knew it was coming. But knowing and living beyond it leaves a hurt and pain deep down in my soul.

I first saw the Big O on a Friday night at John Carroll Athletic Field on Montclair Road in Birmingham, Alabama. I was a junior at John Carroll High School, playing my first full year of organized football. We were a small, rag tag, undersized bunch playing about two classifications above our ability and size level. We didn’t win very often.

The opponent was Fairfield High School. They were good. They had a starter named James Owens, who would later sign with Auburn University, becoming the first African American to integrate a major state university in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi… the Deep South. Now, he was warming up across the field from me. A running back, he was tall, lanky and wore a horse collar around his neck. He was about 6’2” and weighed close to 210 pounds. He looked dangerous. Ready to kick some you know what!

Our coach had warned us about him. He’d then gone on to tell the lie that coaches tell outmanned teams when they are about to get slaughtered by a bigger, faster, better team with bigger, faster, better players.

Referring to Owens, our coach said, “Hey! He’s no better than you. He puts his pants on one leg at a time just like you do.”

We all knew that was bullshit. Putting his pants on like we did had nothing to do with playing the way we did. This guy was All-State in football and track. He ran the 100 hundred-yard dash and threw the shot-put. He was a monster. I was glad as hell I wasn’t on defense.

It wasn’t pretty. He left carnage on the field. I don’t remember the score but it wasn’t close. After it was over, I watched him walk off the field where he had dominated us. Having integrated Fairfield High School football he was now heading off to be one of the first blacks in the Southeastern Conference.

Two years later, I would join James and Virgil Pearson, also from Fairfield, and Auburn’s first African American Athlete, Henry Harris, at Auburn University.

As a basketball player, Henry often travelled in different circles. For Virgil and me, James became our Daddy. We nicknamed him “Daddy O.” He was strong like our fathers, but gentle towards us, who had followed him. We not only respected him, everybody, on and off the field and in the athletic complex, held James in high esteem. Integration made things socially awkward but everybody respected James for his quiet, dignified courage. That respect lasted all of his life.

Our special friendship lasted from 1970 until his death. Like close friends we drifted apart throughout the seasons of our lives but we always found each other again because of the love and respect we had for our shared experience.

Henry left Auburn University after his senior basketball season. Virgil left his sophomore year, looking for a different experience. For the next two years on the varsity football team It was just James and me, as athletes of color. For the rest of his life we always relived that experience.

Between us we realized there was no one else in the world who shared that loneliness, that moment in our lives where we carried the pail of integration uphill without much assistance from those who could have helped us along. Those times were about providing for those whom would follow. We knew that. It kept us going.

James kept me grounded. He talked me down many times when, emotionally, I was way over the top. Over time, we embraced our teammates and they embraced us with that special bond that comes from the shared experiences of being teammates and winning games. During the two years when James and I were the two black pioneers on the team, we won 19 games and lost 3. We were a part of something bigger than us.

Throughout the decades that followed we talked a lot about those times. We always circled back to that experience. What had been a painful part of our lives had become, by the 21st century, a memory of achievement, a gift that we gave to all who followed at our university, not just the black athletes. We also grew to love our teammates and they loved us back. Today we are teammates for life. It ‘s more than a slogan. We live it.

James is an Auburn University icon. He doesn’t need for me to tell everyone about his contributions. Look around the university and you will see his accomplishments in the faces of the young men on the football team, the basketball team, the track team, the baseball team and in the faces of the young women on the softball team, the basketball team and all the other sports that did not exist before integration.

He will always be remembered for what he gave to Auburn University, the state of Alabama and college football. I will always remember him as my friend.

I’ve been involved in Television since the late 1970s. In those days of yesterday, I worked in television news at the local CBS affiliate in my hometown of Birmingham, Alabama. I was young, fresh, and somewhat of a hit in town because I had made a name for myself as pioneering black athlete at Auburn University. I was also one of the first two blacks anchors to be featured on the television evening news in Birmingham. It was fun! I learned a lot from very experienced people who were outstanding at what they did. I’m grateful to them for what they taught me.

In the 1980s I did my first paid acting gigs. Some were for big screen movie theatres and many were for the small screen of television. I occasionally continue to do these, working as an actor for the big three networks, CBS, ABC, NBC, and pay channel HBO, among others. These jobs have always been fun, paid well, provided work opportunities throughout the United States, and opportunities to attend dress-up, star studded premiere parties in Los Angeles. I’ve worked with stars Carroll O’Connor, Della Reese, Brad Pitt, Ed Norton, Candice Bergen, Luther Vandross, Sally Field, Alfree Woodward, Lawrence Fishburne and many, many others.

One season, I hired on as a radio sports analyst for a Canadian League football team and traveled all across Canada broadcasting games.

Never satisfied, and always seeking more, I’ve written a play, had it produced in Los Angeles, and wrote an autobiography that was published and sold in national retail outlets.

So it seems only natural, at least to me, that an evolutionary move would be to write, produce and direct a film for broadcast television.

That’s where Quiet Courage comes in. Quiet Courage is the story of James Owens, the first African American college scholarship football player in the powerful Southeastern Conference Deep South states of Alabama, Georgia and Mississippi. Owens made history by signing with Auburn in 1969. He says now “I didn’t know what I was getting into.” My two favorite taglines from the film’s promotional materials are, “Owens loved his University. She learned to love him back;” and, “He was Bo Jackson before there was a Bo Jackson.” The film premiered on Auburn’s campus on November 10 to a sold out crowd of 350 excited and very appreciative supporters, who laughed, cried, and stood to applaud as the ending credits rolled.

Back to television. The film Quiet Courage will make its broadcast debut on November 26th on the nine-station network belonging to Alabama Public Television. To say I’m excited is an understatement. Working as talent on television is a role I enjoy, but producing, writing, guiding and directing this project from ideas, to concept, financing, preproduction, hiring, collaboration, post production and identifying a broadcast partner is a joyful feeling of immense satisfaction.

Quiet is quite a story. It’s a story I’ve always wanted to tell. James is my friend. We were roommates for a couple of years at Auburn. I lived much of his story with him. To be entrusted with it is quite an honor. If past experience is an example, Quiet Courage will be around for a while. Talks with other broadcasters continue. DVDs are for sale at bestgurl.com.Check it out. You’ll laugh, cry, and gain a full appreciation for the film’s title and its relevance to the protagonist. Quiet Courage, “the ability to face difficulty, uncertainty, or disturbance without being deflected from a chosen course of action.”

If work is supposed to be fun, I’m having a ball. For the past year I’ve been working on a project that feeds my soul and in the words of the old Native American Chief in the film Little Big Man “causes my heart to soar like a hawk.” Quiet Courage, a film documentary on my good friend James Owens gets my juices flowing.

James Owens has been my friend since 1970. We were pioneers of college football integration at Auburn University. When we played black players in the Southeastern conference of college football were relegated to one or two per team.

In comparison to James I had it easy. He was the first African American football player in Auburn’s history.

The loneliness, the slurs, the suppression of hurts and emotions stayed with me a long time. It was three decades before I could express it in this manner or any manner. It was many years before I could bring myself to talk about it with my wife and son. Just couldn’t. It was too painful.

But this isn’t about me: Nor about the pain. It’s about my friend and his forty-year relationship with Auburn University.

“I had no idea what I was getting myself into,” James tells me. “I had no idea of the magnitude of being the first black.”

In 1969, James Owens realized a portion of Martin Luther King’s dream. He fulfilled the legacy of Jackie Robinson. He answered prayers of many blacks and some whites in the state of Alabama by answering Auburn’s call to play football at the University. What has followed over the last forty years is a love story.

Not knowing what to do to aid their only black football player and only the second black athlete in Auburn Athletic history, Auburn attempted to treat James as if he was no different than the other athletes. “We treat all our athletes the same” was the philosophy.

Imagine being the only white among a team of blacks. Imagine being the only white in a University of 15,000 blacks where everyone, students, alumni, whites and blacks examine your every move. Imagine there are so few people who look like you on the campus, that your social life consists of sitting in the TV room after games while all your teammates are out partying and enjoying the spoils of victory. Imagine being seventeen and having no family, nearby. Imagine possessing a second rate education, a by-product of segregation that leaves you inadequate in the classroom. Imagine.

Quiet Courage explores these issues and others as told by James, his teammates former coaches and friends. It’s introspective, funny, sad, and full of love. Mistakes were made. James did not graduate. He didn’t play professional football. The University brought him back as a graduate assistant to get his degree. The rules were changed and he was asked to leave. He wandered. Jobs came and went. His wife Gloria who he met when she became one of the few black women at Auburn his senior year, became his salvation.

Then he found the ministry. Saving souls was as tough as scoring against bigotry, but it was more rewarding. His church was only forty miles from where he’d made history, but he didn’t venture close to campus. Nor did the University reach out to him. Love relationships are like that.

Fate intervened. His nephew, Ladarious signed a scholarship to play football at Auburn. James was drawn back to his Alma Mater. This time it was different. Auburn loved him back. Auburn Athletics created the James Owens Award of Courage to honor him. He received his award and a standing ovation in front of 86,00 Auburn fans. Auburn named him an Auburn legend and he was honored at the SEC Legends dinner with other legends from the conference before the 2012 championship game.

Life was good. He was back in the fold. His teammates honored him as the soul of the 10-1, 1972 team known as the Amazins, one of the favored teams in Auburn history.

Then came the diagnosis. His heart was failing. Tears followed. His teammates and the University rallied to his side. Letters, phone calls, and loads of love poured in.

Yes. He realized, they loved him, not only as a football player but, as James Owens, the human being who notched his name in the Auburn history book.

He had one regret. He never received his degree.

The phone call from the Auburn administrators shocked him. The robe, the march, the arena full of the Auburn family, his name called, the honorary degree handed to him, his acceptance speech. He was an Auburn University graduate.

They were back together again, a happy ending. Just like in the movies.