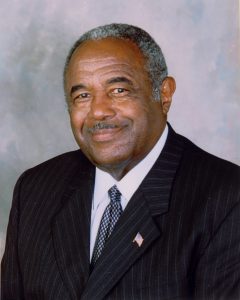

Chris McNair has died.

My first memory of him is of my being a little boy and greeting him as he brought the milk to our front door. A gregarious man, dressed in white and driving a White Dairy Milk Truck he was the milkman who my parents and aunts knew. Later, after I finished college and moved home to Birmingham, I went to work with him on his magazine, Down Home.

Down Home showcased his beautiful award-winning photography of people and places in the Deep South. I wrote many of the magazine’s articles both under my name and my pseudonym, Dwayne Stanley. We sold the magazine all over Alabama and to those black transplants who had generationally been a part of the great migration from the southern states to the good life, “up north.”

Working full time for BellSouth/AT&T, I would leave work, change clothes, get a bite to eat and spend the evenings at his studio, working with him on story ideas, accounting for the ads and magazines I had sold, and more importantly we would sit and talk. Because I had known him for so long, he always referred to me as “boy,” but that was okay. In terms of what I would learn from him, I was a boy.

Much has been written and discussed about him, the tragic death of his daughter in the

16th street Baptist Church bombing, his artistry as a photographer, his many civic and personal attributes, his time as a politician and his fall from grace. But for me it’s the nights we spent in his studio, talking, me mostly listening.

He often asked me about life at Auburn University where he would later send one of his daughters. He was interested in what life was like in the downtown corporate power structure, where I had “a good job.” I often detected regret at his having come along “too early,” to enjoy the rewards of integration.

Only once did I ever see him lower the barrier of his manhood and break down in tears as any man would who had experienced the life he had experienced, from Fordyce, Arkansas, to Tuskegee, to Birmingham, to the bombing at the sixteenth Street Baptist Church and the tragic loss of his daughter. “Why do we have to go through this?” he wailed, tears streaming down his face.

I didn’t say a word. It was his moment. I sat in silence.

I suppose I should say Chris McNair went to prison for stealing the people’s money. I’m a believer that you don’t run away from your history. He didn’t. He pled guilty to that crime. But if there was ever an elected official that the public wished could have been forgiven it was Chris McNair. He’d suffered enough many said. The crime and punishment was a testament to the contradictions of life. We can be upstanding in the light of day and perhaps do what we feel we need to do when the shadows of darkness surround us.

My memories will always be of the man I got to know personally and intimately, a man who during a five-year stint in my life became a mentor and friend. Toiling and talking in his junked-up studio, we strived to shine a light on what was happening “Down Home.”

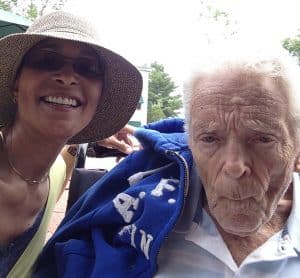

We met him in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris twenty years ago. He always said he was attracted to my wife’s (joyce) stylish hat, or at least that was his story and he stuck to it. An art history professor, an American living in Paris, he invited us to join him on a tour he was giving to his students. “Would you and your man like to join us?” he asked joyce. With an invitation like that, how could we not? “Yes,” we agreed. For the next two hours we listened and learned. The man was a walking, talking art history lesson. After the tour, we were invited to lunch with the group. We politely declined, figuring we had imposed enough on their time.

As we exited the museum, I mentioned to joyce that we should have gotten the gentlemen’s contact information so we could send him a nice note of thanks. She confidently replied, “Oh we’ll see him again.” True to my name as a doubting Thomas, I confidently spouted, “We’ll never see that man again!” Two days later, while lunching at an outdoor café, joyce jumped up shouting, “There he is.”

“Who?” I asked. She was already giving chase. “The Professor,” she replied on the run.

She brought him back to our table. That evening we had dinner with him and his friends who were also Americans living in Paris. After that we visited for the next twenty years until his passing in March of this year. He came to our homes in Fort Walton Beach, Florida and Birmingham, Alabama. We visited him in Maine after he moved back to the states.

A physically short man with encyclopedic knowledge and an inquisitive mind regarding social issues, he was stimulating to be around. We went to a jazz performance on the River Seine in Paris. We went to the Moulin Rouge. He spent a Christmas with us in Fort Walton. He visited us in Birmingham for the premiere of my play, Speak of Me As I Am. Issues of ethnicity and American racism peaked his interest and touched off lively conversations. He always inquired about our son, Dixson. He was just incredibly special! I will never forget him.

The last time we saw him was in Maine two years ago. Living with his son Peter, he was confined to a wheel chair, but insisting that he would go back to his beloved Paris as soon as he was able. This month, in his 9th decade, weak and frail, he passed away.

His son Peter posted a wonderful picture of him with his beloved glass of wine and a twinkle in his eye. Brandt Kingsley, you were one of a kind!

I was looking through some friend requests on Facebook, when a smiling face jumped out at me. Before I confirmed it, I looked to make sure it wasn’t Spam. I also checked out the mutual friends we shared. There were five, a couple of the names looked familiar. A closer look, and I discovered that I recognized three of the five. I looked again at the request, the name and the photo. I grinned a big grin. The kind of grin reserved for those who have touched your soul.

Robert! He was one of my guys. Back in the 1970s, after graduating Auburn and moving back to Birmingham, I worked as a supply teacher at the legendary Parker High School. I subbed in the classroom. The legendary principal, Bubba Thompson also made me his B-Team football coach. The Facebook request was from one of my players. Our mutual friends were also my players.

I only coached that one season, the siren song of television beckoned. We went 2-2-1. I can say as a coach I never had a losing season.

What has stayed with me and really matters are those guys and the relationships we built. They were young men searching for the person they would grow into, the way we all do at fifteen. They gave themselves to me.

Robert, a running back, always wore a smile. He was pleasant to be around. I wonder if his voice has grown into his body. He had a high-pitched voice. He loved to run the football. To be good, or great, a running back has to love to run the football. Robert wanted the ball.

The other guys on the list, Drake a linebacker, was smart, a thinker. Hardy, an offensive lineman, also very smart, a leader. Harrison, was a big kid, a running back, who would grow into a young man that could continue playing after high school. He was also smart.

I see Jake at Niki’s West in Birmingham. Niki’s has to be the most popular meat and three restaurant in Birmingham. Jake is a server. He was tall and rangy and played safety for us. His real name isn’t Jake, we renamed him after the Jake Scott who played at Georgia and with the Miami Dolphins. It is always good to see Jake.

The one recurring theme in my descriptions of these young men during their High School days is their smarts. They were good athletes, very respectful and also pursued their academics with the vigor of a big game against Carver.

They were wise enough to wonder what was next for their lives. The lure of big time college football was just spreading to the masses of southern black athletes. That was not in the picture. There was not the carrot of the NFL. There were no all-star camps to attend. ESPN was a thought in someone’s mind. My guys accepted this time in their lives for what it was, a wonderful season of life. One that would keep them bonded.

I am proud that I got to spend that year at Parker. Its reputation is outstanding. At the time it was a community public school. The black students who attended there would come from all over Birmingham. Most of my guys lived in the nearby community.

Whenever I am in Birmingham and I hear the word “Coach” directed at me I know it’s one of my players or students from that era. They are the only ones who call me “Coach.” It’s special!

I’m proud of my guys. They are all productive citizens doing what they can for their families, their communities and each other. I am so honored that they would want to keep in touch with the old coach, who only coached one season. My grin grows. They gave me one of the most wonderful seasons of my life.

(As published on westernjournalism.com, Sept. 28, 2017)

I saw him last spring in Montgomery, Alabama. I was there to speak to a Leadership Montgomery group. As I looked out over the crowd, he sat there, grinning. Grinning at me! Grinning as if he had a secret no one else in the room knew. As it turns out he did. It wasn’t until a few weeks ago, we found the time to get together and talk about it.

The story travels back into not only my past, but also, our mutual history. Back into a time I call yesteryear. Memories fade. Details get fuzzy but the essence of the story, he remembers in full.

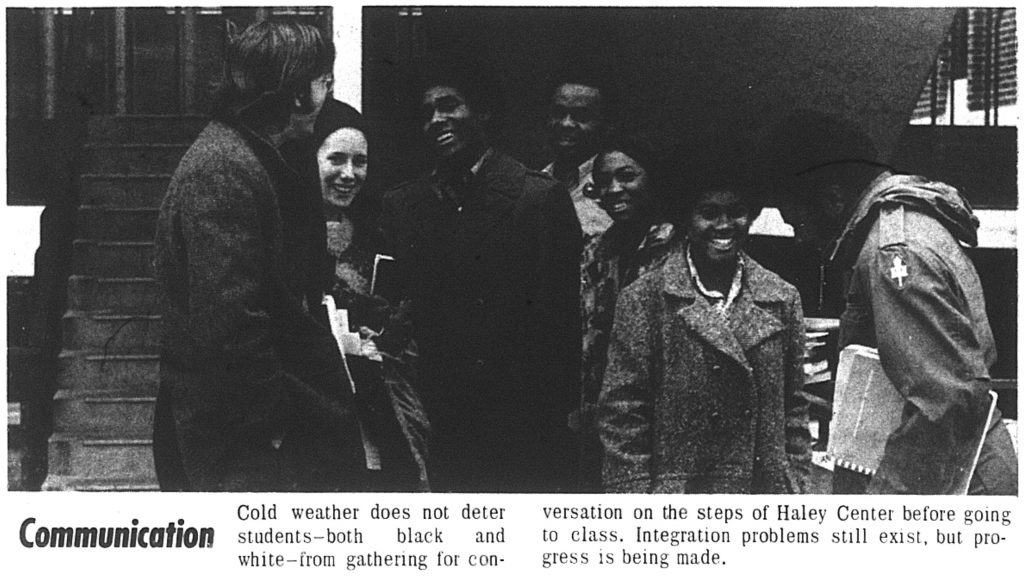

We were freshmen at Auburn University. We had at least one class together. We obviously struck up a relationship.

Sam Johnson tells it like this. We both started Auburn in fall 1970. As freshmen we were coming at the early integration of the University from different perspectives. Sam is white. He chose to get to know me. Not just in class and not just as an athlete. Sam chose to befriend me and get to know me in a time when not many on the white side of the integration experiment at Auburn chose to cross over to that other side. He could have chosen to avoid the integration debacle. It wasn’t his fight. He was secure socially in a fraternity and had the advantage of not being the first in his family to venture to Auburn. I was at the other end of that spectrum.

When we met this September, Sam remembers, that we talked a lot in those days; or rather I talked… a lot. Sam says I was angry and voiced my anger to him about the experience between classes while sitting outside of The Haley Center building. Some of that is fuzzy for me but I don’t doubt I was angry. I do wonder about my sharing my feelings with him. That was something I did not do with people I did not know well. It was part of my anger. Integration was lonely, boring, demeaning and more like the drudgery of a miserable mission than a fun education experience. Today when I hear my fellow white alums from that era or teammates tell stories of their college days, I wonder if we went to the same University. The few of us black students who ventured into integration during that time were pioneers on a mission to make things better for those who would follow. Was it fun for us? Nope. The black athletes, at that time there were three of us in the Auburn athletic department (1basketball, 2 football), were the forerunners to today’s games, but we were not the beneficiaries of our efforts. I kept who I was and what I was thinking bottled up inside. My insides were tied up in knots, knots of anger. I often kidded some of my white teammates telling them, “If you knew what I was thinking, you’d be scared of me.” Sam must not have been afraid. Because according to Sam, I let him in.

The visible proof of our relationship appeared in the school newspaper, The Plainsman that I would later write for. The paper ran an article on race relations on campus, with an accompanying photo. Sam brought a copy of the photo to our meeting in September. The photo was of Sam and a white female, two other black males: Joe Nathan Allen and Rufus Felton, two black females who I do not remember, and me. We were all smiling. We had been recruited to pose for the picture. Someone walked up to Sam and me and asked if we would pose. Someone else recruited the others. We agreed and met the others on the steps outside Haley Center. In the photo we were all smiling like friends. Sam did not know any of the others, just me.

The cut line under the photo in The Plainsman read, Communication. Cold weather does not deter students both black and white from gathering for conversation on the steps of Haley Center before going to class. Integration problems still exist but progress is being made.

The photo is dated February 12, 1971.

Sam caught hell from some of his fraternity brothers and others for being in the photo with five black students. But he went even further. Because of my venting, Sam took it upon himself to go to the University recruiting office and tell the officials what I had said. Not telling on me but repeating the things that I had said needed to be done to make progress at the University. At first he was given the run around but they eventually listened. Auburn administrators even went so far as to put some things in place to recruit more black students and improve the social atmosphere.

Before we left our September meeting, Sam says that I inspired the little progress that was made in those days. I thank him but know that it was in part, credited to him. I could not have gone and done what he did. I would have been viewed as the angry radical in the administrator’s eyes. I could have lost my spot on the team, lost my scholarship, gotten kicked out of school. On the other hand, Sam would not have known what to say if he had not listened to me. When Sam took it to the administrators it became a university problem not just the angry black guy’s problem. He did what I couldn’t do. It takes us all. Sam taught me that. Thanks Sam!

There aren’t many walking around on this earth who are branded by first names only; you know, Cher… Madonna… Bo. My friend “Sterfon” is one of those. You don’t know him? You should! He’s a character! He’s also fun, a great dad, devoted husband, and his name creates ripples in the film and television business.

Sterfon!

Walk into a makeup and hair trailer on many sets in Hollywood and drop his name. Check out the reaction. For those whose misfortune has not brought them into his orbit, there may be a look of puzzlement. For those who have been lucky enough to travel in the same pathway, there are more than likely smiles, laughs, and the question, “Is he here?”

Sterfon Demings is a known entity in “The Business” of film and television. He is a survivor and a hair stylist extraordinaire. I first met him on the television show In The Heat Of The Night, shot in Covington, Georgia, near Atlanta. We didn’t know each other well. He now says he kept his distance from me. “I thought you were an undercover cop,” he laughs.

“Why?” I asked.

“You looked like one. You always had on a suit. You were the City Councilman on the show so you were always with the cops.”

Lots of laughter!

Earlier in my career, I played quite a few lawyers, policemen, and politicians.

A few years after he left Heat, I met him again in Atlanta, on Miss Evers’ Boys. This time we clicked, and have been clicking ever since. We would later work on the short-lived series, City Of Angels.

In between those gigs he has stayed busy; working on Boyz In The Hood, Into The Wild, Italian Job, Beauty Shop, Soul Plane, How Stella Got Her Groove Back, Milk, Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, American Crime Story, Bones, Monster’s Ball and many many more. Those who have sat in his chair include, Alfre Woodard, Sean Penn, Halle Berry, Donald Sutherland, Kristen Stewart, Miles Davis, Ed Norton, Angela Bassett, countless others… and myself.

Sterfon and I had lots of fun in Los Angeles. A boy’s night out on the town generally meant a whole lot of fun and laughter. My trademark introductory greeting to anyone who would listen was a prideful, “I’m from Alabama.” It was always a conversation starter. Intriguing. Sterfon got a kick out of it. Over the years he must have heard it hundreds of times. If I wanted to make him laugh, I only had to say those three words and he could not help himself.

We still enjoy each other’s company. We think of each other as brothers who are grounded as friends because of our core beliefs. Occasionally we pick up the phone and give it a go in a long-winded conversation. Our conversations bounce from family, to The Business, to our memories of nights out on the town in Los Angeles, and of course, Alabama.

TG: You’re from Montgomery, Alabama? What was it like leaving Montgomery, right out of High School, for the bright lights of NYC?

SD: For me, it all started in high school. In high school, I got my cosmetology training in vocational school. I’m grateful because that started me on my career. I discovered my talent. Vocational education? Too bad the high schools don’t do that anymore. Education is vital to career success, I feel.

TG: From high school to being in The Business. Trace your path for me.

SD: I moved to New York. That was a big step. People doubted me but I was pretty determined. Several people tried to talk me out of going. “New York,” coming from Alabama, they made it sound scary but it also became a challenge. I got a job as an apprentice at “The John Atchison Salon,” so I could learn my craft at the professional level. Education was important for me. Quite a few entertainers came in there. Even as an apprentice I wasn’t star struck. So they didn’t intimidate me. The apprenticeship program allowed me to go do some morning talk shows on NY-TV and I met Jackee Harry who was working on the show “227.” We got to be friends. I did her hair. She told me she was moving to California. I told her I was too. She told me she would look me up when I got there.

The salon opened another location in LA. I transferred out here. I soon became part of management and the Educational Director. Jackee kept her word and I worked with her as her stylist from time to time. I left the salon in a dispute. I started off going to people’s houses. Then came the chance to work on “Boyz In The Hood.” After that, I was off and running.

TG: You’ve won industry awards for styling. The annual Hollywood Beauty Awards recognizes the architects of hair, makeup, photography and styling in Hollywood. You have been described as, “An innovative and world-renowned hair designer and stylist, a master hair-cutter.”

SD: Funny, I never used to pay attention to awards. Considered most of them political. But I’m grateful. There’s even an award named for me. “The Sterfon Deming Award.” The person who won it is amazing. I thought it was pretty neat that she went home with an award with my name on it.

TG: Did I fail to mention you were always a snazzy dresser?

SD: Thanks.

TG: You were always a fun guy to have on the set. You would always dress up and do a walk on in one of the scenes. Must have had a good relationship with the Director and Producers?

SD: I was always a fun guy to have around. The crew would always encourage me to jump in somewhere. It was part of my thing. Where is he going to show up in the film? The first time it was in “Boyz N The Hood.” I was in “White Men Can’t Jump.” In “The Piano Lesson” I played a slave. I was also in “The Temptations” and a few others.

TG: Did you want to act?

SD: Not professionally. If I could have done it for fun. But I enjoyed my job.

TG: What’s next for you?

SD: The older you getthe more you realize that it isn’t about the material things or pride or ego. It’s about our hearts and who they beat for.

TG: You’ve become a philosopher?

SD: Beautiful things happen when you distance yourself from negativity.

TG: Any last words?

SD: I’m from Alabama!

TG and SD: Laughing Out Loud!!

Alfre Woodward, the talented actress says to me, “I’ve got someone I want you to meet.”

“Okay,” I agreed.

She led me to a corner seat in the rented party room at the Santa Monica, California Airport. The party was for her husband’s birthday. The room was a who’s who of Hollywood stars having a good time outside the bright lights.

As soon as I saw the guy she wanted me to meet I told her, “I know this guy.” Of course I knew him. He was the secret service agent guarding the President every week on the hit TV show The West Wing.

But… there was something else. I actually knew this guy. He knew me as well. We excitedly shook hands. Alfre said, “I believe you are both from Alabama.”

That was true. He’s from Montgomery. I’m from Birmingham.

But, we’re more than that.

We immediately recognized each other because we’d both gone to Auburn University during the same time period. We had not been close friends, not even close acquaintances. We knew of each other the way you know of someone who has achieved some notoriety on a campus of 20,000 students. He had been involved in student government and his fraternity. I’d played football and written for the school paper.

It didn’t take us long to reacquaint. We soon got together for dinner with our wives and we’ve been fast friends ever since.

Michael O’Neill, “Michael O” I call him, is a professional actor. He knows his business. His IMDb page proves that. He has worked in more than 75 episodes of television and 30 films. Michael O has worked in New York, Los Angeles and across Canada. He’s worked with Alfre Woodard of course, Halley Berry, Martin Sheen, Clint Eastwood, Robert Duvall, and a host of others. Everyone except…

We often say between the two of us we have nearly 50-years of combined experience, more than 115 episodes of television and nearly 40 films. We have worked ER, Cold Case, Without A Trace, Boston Legal, Close To Home, The West Wing, NYPD Blue and Chicago Hope. But never had we worked together, until 2016.

Our Alma Mater, Auburn University, and the whole Auburn Nation was deeply involved in a $1 Billion Fundraising campaign. Michael O, I and others were asked to host, MC and dramatize a live 90 minute show in support of the campaign in Dallas, Houston, Tampa, Atlanta, Birmingham, Nashville, New York, and Washington D.C. We relished the opportunity to work together and to support our Alma Mater.

I caught up with him by phone for this post and it was like old times.

TG: Where are you?

Michael O: Working on a film in Memphis. Where are you?

TG: In Florida. I’m home for the next five days and then off again.

Michael O: Five days sounds like a vacation.

TG: Caught a break. I’m in and out the next three weeks.

TG: I have to ask you; we got to work together on the Auburn Campaign Events. What did it mean to you?

Michael O: It’s nice to give something back. It’s what you hope a college education can do. It reflects further than we could imagine. It’s easy to participate because I believe so strongly in the Performing Arts Center (coming to campus) and not just because you and I are in the arts but also because it’s important to our students and their interest, their outlook and their experience as they go out to shape the world.

TG: Talk about the night Alfre introduced us.

Michael O: That was funny! I remember my daughter Ella was 5-6 weeks old. It was the first time my wife, Mary and I had been out in a long time. We wanted to get out.

I had just worked on a project with Alfre, “The Gun in Betty Lou’s Handbag.” We had so much fun working together.

TG: She’s great. (TG worked with Ms. Woodard on Miss Evers’ Boys).

Michael O: That night in Santa Monica she told me, “I got somebody you got to meet.” She walked up with you and right away I said ‘I know him. We were in school together.’ I knew of you from campus, not just from playing football.

TG: That’s funny I told her the same thing. I know him. That turned out to be a special night.

Michael O: Yep.

TG: Talk about your current project.

Michael O: It’s set in Iraq. A young man goes off to war, gets thrown in the middle of everything and comes back with PTDS. He loses his faith and family. There is a very spiritual message to it. I play his mentor. Military guy.

TG:Do you get immersed in your characters? How far have your gone with this guy you’re playing?

Michael O: I’ve done so many films playing military guys and know quite a few guys. I consider it an honor. They help me with the research. I try to be very respectful. It has to be believable. I tell them, ‘don’t let me get caught acting.’

TG: Of all the projects you’ve done, what’s your favorite character and why?

Michael O: Mr. Pollard in“SeaBiscuit.”One of the first times I’ve wanted something so badly and got it. I blew it wide open in the audition. There were a lot of guys high above me in the food chain who were in line for that job, but they chose me in the audition. The character was actually written better in the film than in the book.

TG: I often like to say the profession is like being a migrant worker. Here today, on to the next gig tomorrow.

Michael O: I’ve worked in so many places. That’s been part of the cultural education. Off the top of my head let’s see what I can name. New York and Toronto several times, Based in LA, so all up and down California; Santa Fe, Salt Lake City, Atlanta, New Orleans, El Paso, all over Texas; Fort Davis Texas, Alpine Texas, Houston, and Austin. Umm, Lexington, Kentucky, Florida, London…

TG: I want you to tell me the Sully story; but first talk about being recognized on the street.

Michael O: (Laughter!) Will Geer (“The Walton’s” and “Jeremiah Johnson”) mentored me. He taught me that it’s more important to be interested in the other person rather than yourself. You have to want to give back to them. You’re sharing an experience with them. It feeds me as much as it does them. Whenever someone recognizes me on the street, my daughters(3) will always bring me back to earth. They roll their eyes at the fact I’m talking to someone I don’t know.

It’s always cool when we’re both together and someone recognizes the both of us.

TG:Yeah that’s always fun!

TG: Tell the Sully story.

Michael O: I’m riding down this elevatorand this guy is stealing glances at me. When the door opens before he gets out, he says, ‘You did a good job, landing that plane on the Hudson River.’ I responded, Thank you!

TG: Any of your girls following in your footsteps?

Michael O: Nope: They’ll find their own way.

TG: What advice do you give to those who ask you about becoming an actor?

Michael O: I tell them, especially if they are asking for their children. I tell them regardless of how far their child goes in the business or if they even get into the actual business part of it; it teaches you so much. Creativity, to run your own business, listening, collaborate with others, teaches you to be observant, teaches you to be in life’s light when it’s your turn and to not be when it’s not.

TG: We still going to do a show together?

Michael O: You bet!

The immediate utterance of “Oh No” spilled from my mouth when first hearing the news of Wayne’s death. It was not long after that I began to smile, and continue to do so when I think of Wayne “Baltimore” Bracy. Baltimore left us on March 21.

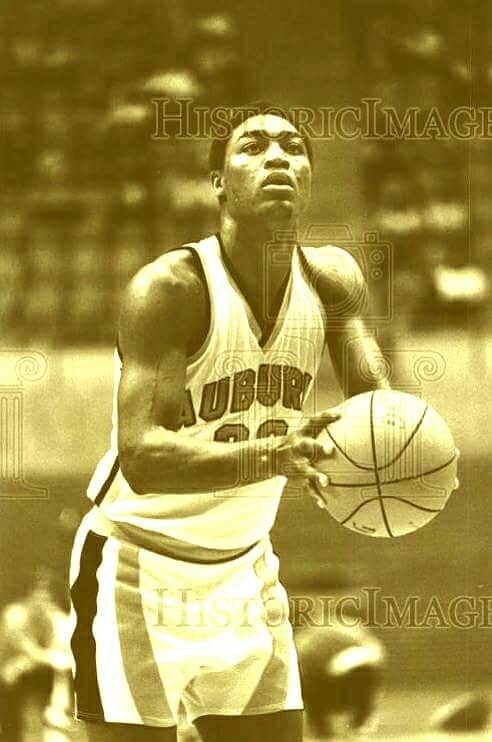

The blogs and postings I’ve read by others speak of a Wayne I did not know, the life he lived after leaving Auburn University. Apparently, he was a dynamic high school basketball coach, for 20 years. He took his team, Deshler High School on five trips to the High School Final Four during his final six years with the team. He was described as very intense and passionate about his coaching. Those who know this part of his life say he was a mentor to a lot of young men and young ladies. All of that sounds like him from earlier days.

I met Wayne in 1974 at Auburn University where he signed to play basketball. Wayne joined a team of stars, two of which, Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell, went on to be stars in the NBA.

1974 was a watershed year for Auburn University and black athletes. In 1970, when I started at Auburn, there were only three black athletes between the football and basketball programs. By 1974, there were 14 black athletes between football, basketball, and the track team. As Sam Cooke sang, “A change gon’ come,” and it was on the way.

Being a senior during Baltimore’s freshman year, I got to know him and acted as a guide - particularly to the young players who were in their first integration experience. Coming from an all-black environment to a nearly all-white one was an adjustment some could not make. Baltimore was a good student; he made the transition.

During that time, so many basketball stars were signed that it was inevitable someone would have to step aside for others, or adjust their role for others to play. Baltimore would not become a big basketball star scoring-wise, with Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell scoring 20 and 18 points respectively and Gary Redding scoring nearly 15. For his career Wayne scored 4 points per game, but he was a contributor, a standout. Some guys become standouts because they can set one role aside and move into another.

Wayne’s role changed. He was a fundamentally sound player who learned from the legendary coach Willie Scoggins at Hayes High School in Birmingham. His strength was guiding the team from the point. Much like Magic Johnson, Wayne could impact the game without scoring. He became a defensive stopper. The other team’s best scorer? Give him to Baltimore. He’d shut him down.

“I have a style all my own,” he told me, referring to his style on the court and how he dressed off-court also. He was stylishly dressed as he walked to class, journeying into his new world. He named himself Baltimore. As long as I knew Wayne that’s what I called him.

As a senior, I tried to have a special relationship with the freshmen. Baltimore and I developed one. I admired the way he carried himself. He had an impact on me.

He was studious, strong, and lived life the way he played defense…man-to-man. Baltimore made an impression on me that has lasted more than 40 years. That’s quite an impression when you consider I haven’t seen him in nearly 20.

On a Friday night, before a Saturday Auburn football game, at the busy, crowded Auburn Hotel and Conference Center, I heard my name called as I entered the lounge. “Hey Thom, come on over here and sit down.” It was a command as much as a request. Charles Barkley was parked in a corner holding court with several guys sitting around him, including another Auburn basketball Legend, Chuck Person, “The Rifleman,” who is now on the Auburn basketball staff. My friend Mychal and I joined them and let’s just say it was a memorable evening.

Charles held court, a king on his throne as he sat with his back to the wall able to see all who entered his domain. For the next couple of hours our laughter rocked the lounge as we cracked jokes at each other’s expense, expounded on sports and politics, enjoyed several beers and pizzas, and of course listened to Charles.

In a crack aimed at me he blurted out to a nearby waitress, “Yeah, I’m out with my Grandfather tonight.” Everybody got a big laugh at my expense. It was that kind of night.

Charles loves Auburn and its people and proved it by posing for at least 50 pictures that night with whomever came forward to ask, children, men, women, past acquaintances and anyone who wandered into the room, discovered that Big Charles was in the house and wanted a photo. Often they would interrupt our conversations, yet Charles was always gracious and we would make room for the person to enter our little domain and get the photo op. I admire his graciousness. He made all who asked feel special.

Charles was in town for the game but also for the announcement that Auburn athletics would honor him with a statue in front of the basketball arena much like the statues of Heisman Trophy winners Bo Jackson, Pat Sullivan and Cam Newton grace the outside of the football stadium. The weekend also included the Bruce (Pearl) and Barkley golf tournament played that Monday with some 120 golfers competing from around the area in support of Auburn basketball.

In typical Charles fashion he asked that his statue be made from a younger picture of him when, as he termed it, “I was skinny.”

“Must be a baby picture,” one of the guys quipped.

The laughter rocked the lounge.

The fun continued throughout the evening.

“I was the leading rebounder in the SEC, when I played with Chuck (Person).” We waited for the punch line. Charles delivered. “Hell it was the only way I could get a shot. Chuck would put it up, baby.”

Chuck could only laugh.

I met Charles for the first time a few years ago. We were both speaking at a conference in Montgomery. I approached him and extended my hand to shake and he put me in a bear hug and held on to me all the while saying “Thank you.”

Puzzled I asked, “For what?”

“You know what you did,” he responded.

“You and the first brothers to come to Auburn made it possible for us.” He responded, referring to the integration of Auburn sports in the late 1960s and early 1970s and those athletes like himself who came behind us early pioneers.

“Thank you.” He said again.

I’ve never forgotten that and never will. That recognition is as important to me as any statue could ever be.

Since then we have been friends, comfortable enough for him to crack me about being his grandfather.

After a couple of hours we drifted up the street to another bar restaurant in downtown Auburn. With Chuck Person having left because of an early morning basketball practice five of us headed up the sidewalk. Heads turned as Charles led the way. A couple of people stopped me to shake hands and relay an Auburn anecdote.

“Hey Charles,” I called out to him as we walked up College Street. “Yeah?” he answered. “Look at all these people looking at us,” I began. I waited until I had all the guy’s attention and then stated. “They’re trying to figure out who the big guy is walking with Thom.” The guys laughed, especially Charles.

As the evening wound down, Charles and a couple of the others decided they would check out another spot before heading back to the hotel. I begged off. Charles couldn’t resist. “Yeah, I know your wife,” he laughed. “Better get on home before you get a whipping.”

I hugged him. It had been a great evening.

Rolling into Atlanta up I-85 north, I approached the interchange outside of downtown that offers the possibilities of north, south, east or west depending on your destination. I chose I-20 west and the flood of memories began.

I spent nearly six years driving this portion of the interstate while working on a television show that lives on in memory, reruns and in many, many hearts. In the Heat Of The Night was my first recurring television experience. Carroll O’Connor hired me as his city councilman, Ted Marcus, on the show.

I rode into downtown Covington, Georgia that had doubled as Sparta, Mississippi on the show and could not stop grinning. I passed the library, which, with signage and several police cars parked out front, doubled as the exterior of the police headquarters. There was the department store that I remembered standing in front of with Howard Rollins as we waited for the director to shout “action,” before walking up the sidewalk and me, (Ted) trying to convince him to run for police chief. It would be my first scene ever on the show and one of the first I’d ever shot. I was a little nervous. I must have passed the test because the producers continued to hire me for the next five years. I passed the park where Carroll, Denise Nicholas and I shot a scene from the episode of “First Girl.” The memories were now a flood.

I had not been back this way since the mid nineties when the show wrapped for good, after 8 years on the air. A reunion of In the Neat of The Night fans and fellow cast mates brought me back to my beginnings.

I parked and walked toward the restaurant where we were all meeting. There were people standing outside. “Ted Marcus is here, ” someone announced as I was walking up the street. Ted was alive once again. It felt good to be Ted again.

Most of the fans had come from several states away. They are all dedicated to the show, know most of the episodes and could quote me Ted’s dialogue from most of the shows I worked. A few of the people gathered called me Thom but most stuck with my TV name Ted. “Ted remember in such and such an episode you said such and such to so and so?” “Ted, remember when you tried to get Virgil to take the Chief’s job?” Ted remember…”

It was like a family reunion on steroids.

I had been contacted last year to attend the first reunion, which I understand was a major affair with over 700 people in attendance and the actors signing and taking photos most of the day. Many of the actors returned for that reunion. I had not been able to attend, as I was fortunate enough to be working another show Containment, at the time. This reunion was smaller, maybe 50 participants. But it was just as special to me.

People came from Indiana, New Jersey, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama and so on and so forth. The have a closed group Facebook page. They are a classy group. The page begins:

Welcome to In The Heat Of The Night Fan Page!

Along with this being a fun group of Heat fans to gather and share love of the show, and movie, there are common sense expectations to follow in the group including, but not limited to- NO NEGATIVE, OR BELITTLING, comments about any actors from the show. No advertising which includes for other groups/pages. (Heat related events and etc. are okay) No political talk. Respect other member’s posts and opinions in the group. Thank you!

It is a great group of people.

While in Covington they go on tours of set locations including to the owner’s houses that doubled as homes for the characters on the show. The owners allow them to tour their homes. The owner of the home where Virgil and Althea lived on the show welcomed a couple of the female fans to spend the night. This has not happened on any other show I’ve worked.

I’ve done about 75 episodes of television, a dozen movies, a couple of hundred commercials, industrials and other productions but there is something different and special about The Heat. It still airs every day sometimes twice a day. Across the country I’ve met fans that are almost religious about it. Many younger people will tell me “my Grandmother loves that show.” “My Dad watches it every day.” It touched souls. It made people happy. That is satisfying to those of us who worked it.

I always knew why it was special to me. It was one of my first. I landed a recurring role on a top ten show and got to learn from some pros. I got to befriend Carroll O’Connor, Howard Rollins and the other actors and crew. It gave me the confidence to continue going forward to what became a career.

Leaving Covington, (Sparta), that evening I knew why Heat was so special to others. Covington, (Sparta) will always be in my heart. Beyond just a television show, obviously we created memories not just for ourselves but also for fans across the country. They thanked me over and over for coming. I thanked them over and over for having me.

The Big O is gone.

My friend. My teammate. The man who helped me through the biggest cultural change of my life is gone. James Curtis Owens died today, March 26, 2016. I knew it was coming. We all knew it was coming. But knowing and living beyond it leaves a hurt and pain deep down in my soul.

I first saw the Big O on a Friday night at John Carroll Athletic Field on Montclair Road in Birmingham, Alabama. I was a junior at John Carroll High School, playing my first full year of organized football. We were a small, rag tag, undersized bunch playing about two classifications above our ability and size level. We didn’t win very often.

The opponent was Fairfield High School. They were good. They had a starter named James Owens, who would later sign with Auburn University, becoming the first African American to integrate a major state university in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi… the Deep South. Now, he was warming up across the field from me. A running back, he was tall, lanky and wore a horse collar around his neck. He was about 6’2” and weighed close to 210 pounds. He looked dangerous. Ready to kick some you know what!

Our coach had warned us about him. He’d then gone on to tell the lie that coaches tell outmanned teams when they are about to get slaughtered by a bigger, faster, better team with bigger, faster, better players.

Referring to Owens, our coach said, “Hey! He’s no better than you. He puts his pants on one leg at a time just like you do.”

We all knew that was bullshit. Putting his pants on like we did had nothing to do with playing the way we did. This guy was All-State in football and track. He ran the 100 hundred-yard dash and threw the shot-put. He was a monster. I was glad as hell I wasn’t on defense.

It wasn’t pretty. He left carnage on the field. I don’t remember the score but it wasn’t close. After it was over, I watched him walk off the field where he had dominated us. Having integrated Fairfield High School football he was now heading off to be one of the first blacks in the Southeastern Conference.

Two years later, I would join James and Virgil Pearson, also from Fairfield, and Auburn’s first African American Athlete, Henry Harris, at Auburn University.

As a basketball player, Henry often travelled in different circles. For Virgil and me, James became our Daddy. We nicknamed him “Daddy O.” He was strong like our fathers, but gentle towards us, who had followed him. We not only respected him, everybody, on and off the field and in the athletic complex, held James in high esteem. Integration made things socially awkward but everybody respected James for his quiet, dignified courage. That respect lasted all of his life.

Our special friendship lasted from 1970 until his death. Like close friends we drifted apart throughout the seasons of our lives but we always found each other again because of the love and respect we had for our shared experience.

Henry left Auburn University after his senior basketball season. Virgil left his sophomore year, looking for a different experience. For the next two years on the varsity football team It was just James and me, as athletes of color. For the rest of his life we always relived that experience.

Between us we realized there was no one else in the world who shared that loneliness, that moment in our lives where we carried the pail of integration uphill without much assistance from those who could have helped us along. Those times were about providing for those whom would follow. We knew that. It kept us going.

James kept me grounded. He talked me down many times when, emotionally, I was way over the top. Over time, we embraced our teammates and they embraced us with that special bond that comes from the shared experiences of being teammates and winning games. During the two years when James and I were the two black pioneers on the team, we won 19 games and lost 3. We were a part of something bigger than us.

Throughout the decades that followed we talked a lot about those times. We always circled back to that experience. What had been a painful part of our lives had become, by the 21st century, a memory of achievement, a gift that we gave to all who followed at our university, not just the black athletes. We also grew to love our teammates and they loved us back. Today we are teammates for life. It ‘s more than a slogan. We live it.

James is an Auburn University icon. He doesn’t need for me to tell everyone about his contributions. Look around the university and you will see his accomplishments in the faces of the young men on the football team, the basketball team, the track team, the baseball team and in the faces of the young women on the softball team, the basketball team and all the other sports that did not exist before integration.

He will always be remembered for what he gave to Auburn University, the state of Alabama and college football. I will always remember him as my friend.