“Our history is our history.” The statement poured from my mouth as I talked to one of my good friends, an Auburn University alumnus about Auburn University athletic integration pioneers, Henry Harris and James Owens. “Who,” you may ask, as you were not around then, or your memory doesn’t extend back that far.

Let me school you.

First of all, recalling history can sometimes be difficult, especially for those who chose to be on the wrong side of that history. We should never run away from our history. When we do, we can very well repeat it. Maybe in another form or fashion, but we can repeat it. We should also never try to rewrite our history to make it fit the circumstances that make us more comfortable. In loving an institution, such as Auburn, which I do, it is imperative for me to also be objective about it. Our history is our history.

I am not a historian. However, I know what I have lived. I know what I witnessed. I know what I saw others go through. I know how those days of early sports integration made me feel. It’s now been fifty years. Auburn University will honor the feats of these two men with a commemoration during the University’s Annual Black Alumni Weekend.

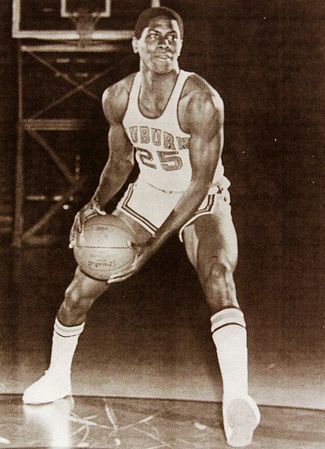

Henry Harris, from Boligee, Alabama was the brave soul who entered first.

Henry broke the color barrier of sports integration at Auburn University in the fall of 1968. It was four years after Auburn University desegregated, due to a court order, by accepting their first and only black student at the time, Harold Franklin. He left three months later.

According to Sam Heys author of Remember Henry Harris: Lost Icon of a Revolution: A Story of Hope and Self-Sacrifice in America. Henry was not only the first black athlete at Auburn he was also the first black basketball or football player on scholarship at any of the, then seven, SEC colleges in the Deep South.

Heys writes that Henry’s signing was more than a college sports issue. “Historically it is important to remember that the integration of college sports was as much a civil rights issue as it was an athletic issue. College sports were the final citadel of segregation in the Deep South. Within a year of Auburn making the first move by signing Harris, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi State all integrated their football or basketball programs. LSU and Ole Miss followed within two years of Harris coming to Auburn.”

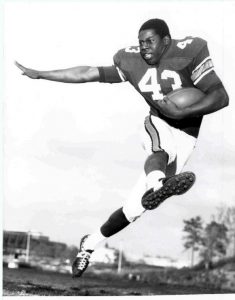

James Owens, from Fairfield, Alabama, walked through the door of sports integration at Auburn next. His chosen sport, football, cast an even brighter spotlight on his integration effort. James often confided to me, that without Henry, he would have left. James said, “I didn’t realize what I was getting into. I thought it would be about playing football where I had excelled all my life but this was more than that. I had to be more than a football player. Everything I did was monitored and watched. I was a hero to the blacks. I was a mystery to the whites.”

In 1968, Auburn essentially became the leader in moving toward equality and justice in the Deep South. Sam Heys writes, “Auburn should be proud of the leadership position it took in signing Henry Harris to a basketball scholarship.” Does that mean that Auburn did everything right? NO! There were plenty of rough patches. It does however highlight Auburn’s willingness to step forward before any of their brethren. It also means Henry and James were willing to take that step along with the University. The University, Henry and James became willing leaders in this great cultural experiment.

Did these men have great careers? On the field they were good. They were leaders, not superstars.

Statistically, Henry averaged 12 points 7 rebounds and 2.3 assists per game. He made third team All-SEC after the ‘71-‘72 season.

In the ‘71 and ‘72 seasons, James averaged 5.1 yards from scrimmage, 29 yards on kick returns, 10 yards on pass receptions and 4.1 yards rushing. Not bad considering the few times he got his hands on the ball.

But far more important than their statistics, they led the way. They led their teams and inspired others, including me. They represented the University well. They sacrificed for others. They opened the floodgates. Personally, they became my big brothers when I joined them at Auburn in 1970.

I witnessed their feats on the basketball court and the football field. I also witnessed their hardships, their loneliness, their courage and their despair. While I was at Auburn, Henry never had a roommate. James and I lived together his last year.

These men may never be in any Sports Hall of Fame. They should be! Does changing a segregated way of life compare with running a touchdown or grabbing a rebound? Are you kidding? Is there any comparison? I know my answer. They may never be included with the outstanding athletes whose names are carved in cement on the streets of downtown Auburn or whose busts are included in the SEC Hall of Fame. But they belong there. Plain and simple, they belong there.