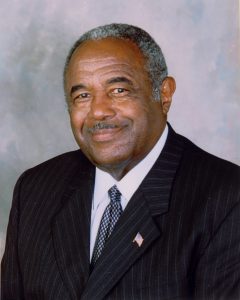

Chris McNair has died.

My first memory of him is of my being a little boy and greeting him as he brought the milk to our front door. A gregarious man, dressed in white and driving a White Dairy Milk Truck he was the milkman who my parents and aunts knew. Later, after I finished college and moved home to Birmingham, I went to work with him on his magazine, Down Home.

Down Home showcased his beautiful award-winning photography of people and places in the Deep South. I wrote many of the magazine’s articles both under my name and my pseudonym, Dwayne Stanley. We sold the magazine all over Alabama and to those black transplants who had generationally been a part of the great migration from the southern states to the good life, “up north.”

Working full time for BellSouth/AT&T, I would leave work, change clothes, get a bite to eat and spend the evenings at his studio, working with him on story ideas, accounting for the ads and magazines I had sold, and more importantly we would sit and talk. Because I had known him for so long, he always referred to me as “boy,” but that was okay. In terms of what I would learn from him, I was a boy.

Much has been written and discussed about him, the tragic death of his daughter in the

16th street Baptist Church bombing, his artistry as a photographer, his many civic and personal attributes, his time as a politician and his fall from grace. But for me it’s the nights we spent in his studio, talking, me mostly listening.

He often asked me about life at Auburn University where he would later send one of his daughters. He was interested in what life was like in the downtown corporate power structure, where I had “a good job.” I often detected regret at his having come along “too early,” to enjoy the rewards of integration.

Only once did I ever see him lower the barrier of his manhood and break down in tears as any man would who had experienced the life he had experienced, from Fordyce, Arkansas, to Tuskegee, to Birmingham, to the bombing at the sixteenth Street Baptist Church and the tragic loss of his daughter. “Why do we have to go through this?” he wailed, tears streaming down his face.

I didn’t say a word. It was his moment. I sat in silence.

I suppose I should say Chris McNair went to prison for stealing the people’s money. I’m a believer that you don’t run away from your history. He didn’t. He pled guilty to that crime. But if there was ever an elected official that the public wished could have been forgiven it was Chris McNair. He’d suffered enough many said. The crime and punishment was a testament to the contradictions of life. We can be upstanding in the light of day and perhaps do what we feel we need to do when the shadows of darkness surround us.

My memories will always be of the man I got to know personally and intimately, a man who during a five-year stint in my life became a mentor and friend. Toiling and talking in his junked-up studio, we strived to shine a light on what was happening “Down Home.”

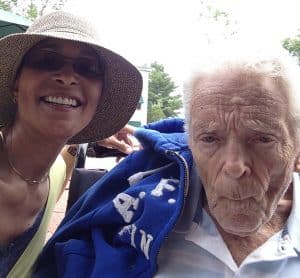

We met him in the Musée d'Orsay in Paris twenty years ago. He always said he was attracted to my wife’s (joyce) stylish hat, or at least that was his story and he stuck to it. An art history professor, an American living in Paris, he invited us to join him on a tour he was giving to his students. “Would you and your man like to join us?” he asked joyce. With an invitation like that, how could we not? “Yes,” we agreed. For the next two hours we listened and learned. The man was a walking, talking art history lesson. After the tour, we were invited to lunch with the group. We politely declined, figuring we had imposed enough on their time.

As we exited the museum, I mentioned to joyce that we should have gotten the gentlemen’s contact information so we could send him a nice note of thanks. She confidently replied, “Oh we’ll see him again.” True to my name as a doubting Thomas, I confidently spouted, “We’ll never see that man again!” Two days later, while lunching at an outdoor café, joyce jumped up shouting, “There he is.”

“Who?” I asked. She was already giving chase. “The Professor,” she replied on the run.

She brought him back to our table. That evening we had dinner with him and his friends who were also Americans living in Paris. After that we visited for the next twenty years until his passing in March of this year. He came to our homes in Fort Walton Beach, Florida and Birmingham, Alabama. We visited him in Maine after he moved back to the states.

A physically short man with encyclopedic knowledge and an inquisitive mind regarding social issues, he was stimulating to be around. We went to a jazz performance on the River Seine in Paris. We went to the Moulin Rouge. He spent a Christmas with us in Fort Walton. He visited us in Birmingham for the premiere of my play, Speak of Me As I Am. Issues of ethnicity and American racism peaked his interest and touched off lively conversations. He always inquired about our son, Dixson. He was just incredibly special! I will never forget him.

The last time we saw him was in Maine two years ago. Living with his son Peter, he was confined to a wheel chair, but insisting that he would go back to his beloved Paris as soon as he was able. This month, in his 9th decade, weak and frail, he passed away.

His son Peter posted a wonderful picture of him with his beloved glass of wine and a twinkle in his eye. Brandt Kingsley, you were one of a kind!

(As published on westernjournalism.com, Sept. 28, 2017)

I saw him last spring in Montgomery, Alabama. I was there to speak to a Leadership Montgomery group. As I looked out over the crowd, he sat there, grinning. Grinning at me! Grinning as if he had a secret no one else in the room knew. As it turns out he did. It wasn’t until a few weeks ago, we found the time to get together and talk about it.

The story travels back into not only my past, but also, our mutual history. Back into a time I call yesteryear. Memories fade. Details get fuzzy but the essence of the story, he remembers in full.

We were freshmen at Auburn University. We had at least one class together. We obviously struck up a relationship.

Sam Johnson tells it like this. We both started Auburn in fall 1970. As freshmen we were coming at the early integration of the University from different perspectives. Sam is white. He chose to get to know me. Not just in class and not just as an athlete. Sam chose to befriend me and get to know me in a time when not many on the white side of the integration experiment at Auburn chose to cross over to that other side. He could have chosen to avoid the integration debacle. It wasn’t his fight. He was secure socially in a fraternity and had the advantage of not being the first in his family to venture to Auburn. I was at the other end of that spectrum.

When we met this September, Sam remembers, that we talked a lot in those days; or rather I talked… a lot. Sam says I was angry and voiced my anger to him about the experience between classes while sitting outside of The Haley Center building. Some of that is fuzzy for me but I don’t doubt I was angry. I do wonder about my sharing my feelings with him. That was something I did not do with people I did not know well. It was part of my anger. Integration was lonely, boring, demeaning and more like the drudgery of a miserable mission than a fun education experience. Today when I hear my fellow white alums from that era or teammates tell stories of their college days, I wonder if we went to the same University. The few of us black students who ventured into integration during that time were pioneers on a mission to make things better for those who would follow. Was it fun for us? Nope. The black athletes, at that time there were three of us in the Auburn athletic department (1basketball, 2 football), were the forerunners to today’s games, but we were not the beneficiaries of our efforts. I kept who I was and what I was thinking bottled up inside. My insides were tied up in knots, knots of anger. I often kidded some of my white teammates telling them, “If you knew what I was thinking, you’d be scared of me.” Sam must not have been afraid. Because according to Sam, I let him in.

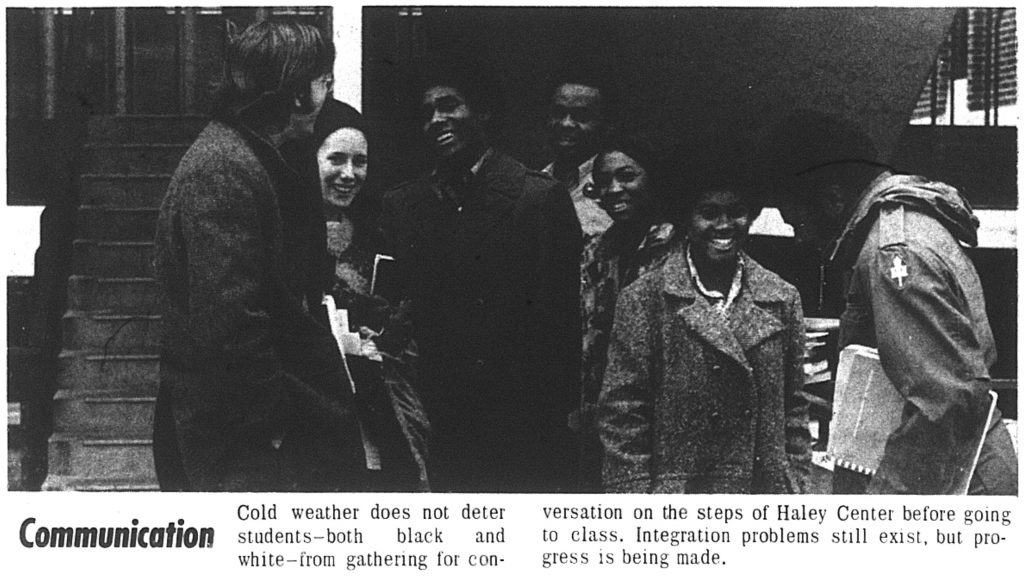

The visible proof of our relationship appeared in the school newspaper, The Plainsman that I would later write for. The paper ran an article on race relations on campus, with an accompanying photo. Sam brought a copy of the photo to our meeting in September. The photo was of Sam and a white female, two other black males: Joe Nathan Allen and Rufus Felton, two black females who I do not remember, and me. We were all smiling. We had been recruited to pose for the picture. Someone walked up to Sam and me and asked if we would pose. Someone else recruited the others. We agreed and met the others on the steps outside Haley Center. In the photo we were all smiling like friends. Sam did not know any of the others, just me.

The cut line under the photo in The Plainsman read, Communication. Cold weather does not deter students both black and white from gathering for conversation on the steps of Haley Center before going to class. Integration problems still exist but progress is being made.

The photo is dated February 12, 1971.

Sam caught hell from some of his fraternity brothers and others for being in the photo with five black students. But he went even further. Because of my venting, Sam took it upon himself to go to the University recruiting office and tell the officials what I had said. Not telling on me but repeating the things that I had said needed to be done to make progress at the University. At first he was given the run around but they eventually listened. Auburn administrators even went so far as to put some things in place to recruit more black students and improve the social atmosphere.

Before we left our September meeting, Sam says that I inspired the little progress that was made in those days. I thank him but know that it was in part, credited to him. I could not have gone and done what he did. I would have been viewed as the angry radical in the administrator’s eyes. I could have lost my spot on the team, lost my scholarship, gotten kicked out of school. On the other hand, Sam would not have known what to say if he had not listened to me. When Sam took it to the administrators it became a university problem not just the angry black guy’s problem. He did what I couldn’t do. It takes us all. Sam taught me that. Thanks Sam!

Rolling into Atlanta up I-85 north, I approached the interchange outside of downtown that offers the possibilities of north, south, east or west depending on your destination. I chose I-20 west and the flood of memories began.

I spent nearly six years driving this portion of the interstate while working on a television show that lives on in memory, reruns and in many, many hearts. In the Heat Of The Night was my first recurring television experience. Carroll O’Connor hired me as his city councilman, Ted Marcus, on the show.

I rode into downtown Covington, Georgia that had doubled as Sparta, Mississippi on the show and could not stop grinning. I passed the library, which, with signage and several police cars parked out front, doubled as the exterior of the police headquarters. There was the department store that I remembered standing in front of with Howard Rollins as we waited for the director to shout “action,” before walking up the sidewalk and me, (Ted) trying to convince him to run for police chief. It would be my first scene ever on the show and one of the first I’d ever shot. I was a little nervous. I must have passed the test because the producers continued to hire me for the next five years. I passed the park where Carroll, Denise Nicholas and I shot a scene from the episode of “First Girl.” The memories were now a flood.

I had not been back this way since the mid nineties when the show wrapped for good, after 8 years on the air. A reunion of In the Neat of The Night fans and fellow cast mates brought me back to my beginnings.

I parked and walked toward the restaurant where we were all meeting. There were people standing outside. “Ted Marcus is here, ” someone announced as I was walking up the street. Ted was alive once again. It felt good to be Ted again.

Most of the fans had come from several states away. They are all dedicated to the show, know most of the episodes and could quote me Ted’s dialogue from most of the shows I worked. A few of the people gathered called me Thom but most stuck with my TV name Ted. “Ted remember in such and such an episode you said such and such to so and so?” “Ted, remember when you tried to get Virgil to take the Chief’s job?” Ted remember…”

It was like a family reunion on steroids.

I had been contacted last year to attend the first reunion, which I understand was a major affair with over 700 people in attendance and the actors signing and taking photos most of the day. Many of the actors returned for that reunion. I had not been able to attend, as I was fortunate enough to be working another show Containment, at the time. This reunion was smaller, maybe 50 participants. But it was just as special to me.

People came from Indiana, New Jersey, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama and so on and so forth. The have a closed group Facebook page. They are a classy group. The page begins:

Welcome to In The Heat Of The Night Fan Page!

Along with this being a fun group of Heat fans to gather and share love of the show, and movie, there are common sense expectations to follow in the group including, but not limited to- NO NEGATIVE, OR BELITTLING, comments about any actors from the show. No advertising which includes for other groups/pages. (Heat related events and etc. are okay) No political talk. Respect other member’s posts and opinions in the group. Thank you!

It is a great group of people.

While in Covington they go on tours of set locations including to the owner’s houses that doubled as homes for the characters on the show. The owners allow them to tour their homes. The owner of the home where Virgil and Althea lived on the show welcomed a couple of the female fans to spend the night. This has not happened on any other show I’ve worked.

I’ve done about 75 episodes of television, a dozen movies, a couple of hundred commercials, industrials and other productions but there is something different and special about The Heat. It still airs every day sometimes twice a day. Across the country I’ve met fans that are almost religious about it. Many younger people will tell me “my Grandmother loves that show.” “My Dad watches it every day.” It touched souls. It made people happy. That is satisfying to those of us who worked it.

I always knew why it was special to me. It was one of my first. I landed a recurring role on a top ten show and got to learn from some pros. I got to befriend Carroll O’Connor, Howard Rollins and the other actors and crew. It gave me the confidence to continue going forward to what became a career.

Leaving Covington, (Sparta), that evening I knew why Heat was so special to others. Covington, (Sparta) will always be in my heart. Beyond just a television show, obviously we created memories not just for ourselves but also for fans across the country. They thanked me over and over for coming. I thanked them over and over for having me.

One yard. A big giant step. One yard and your life changes. One yard from glory.

Former ballplayers have the best stories. The good talkers can take an incident from a game many years ago and make it the centerpiece of speeches that they give long after they have finished playing. The “formers,” can be funny, heart wrenching, give inside looks at the teams in their respective eras, inside look at great stars. Randy Campbell is good at it.

Randy is one of the good guys. Today he is a financial advisor in his business Campbell Wealth Management. We serve on the Auburn University Foundation Board together. Imagine that two former football players. We made the transition.

I didn’t know Randy well before he came on the board a year ago. We played in different decades at Auburn. I knew of him. He played quarterback in the 1980s, on some great Auburn teams. He is a great speaker. Randy jokes he was famous for handing off to all-everything runner Bo Jackson. There is some truth to that. Bo was the truth so why not?

Still, Randy was no slouch. He is well remembered. He was 20-4 as a starting quarterback. In the 1983 Tangerine Bowl, he became the answer to a TV trivia question. “The 1983 Tangerine Bowl featured two Heisman Trophy winners, Bo Jackson and Doug Flutie. Who was the MVP?” The answer, Randy Campbell!

Back to Randy’s story. He relishes telling it. It’s like the secret only he thought of.

Here goes.

It’s the 1984 version of the Iron Bowl rivalry game Auburn vs Alabama. It’s a game that Bo will make famous with his “Bo Over the Top” leap at the goal line to give Auburn the victory over Alabama 23-22.

Randy tells the story.

“It’s third down, we’re threatening to score. I throw a swing pass out to Bo. Bo takes it down to the one-yard line. He almost scored. He came up a yard short. Of course he then goes over the top on the next play for the winning touchdown.”

I’m waiting for the punch line. Randy wears his “I’ve got a secret” look on his face.

“If he had scored on the swing pass, instead of “Bo Over the Top,” the headline could have read, “Campbell throws the winning TD in victory over Alabama.” Instead Bo was close, so close, tackled at the one-yard line. Man, I was one yard from glory.”

He looks me in the eye. I grin. It’s a great story. Crowd pleaser. Crowds like self-deprecating humor, especially from athletes who have been at the top of the food chain.

Sports is full of close, almost, damn near, shoulda, woulda, coulda, one play here, one play there type moments. If only such and such, stays safely locked in our memories many years later.

One yard from Glory!

I’ve embellished Randy wanting to be the hero. He is a pretty humble guy. All winning team oriented athletes will tell you, what mattered is that their team won far more than they lost. The team is what counts.

Randy says that. But like many of us “formers” he likes to have fun with his stories.

He says, “I told that story to Bo. I said, ‘Man, if you hadn’t gotten tackled on the one-yard line, the headline would have been “Campbell Tosses Winning TD” instead of Bo Over the Top.’ He wasn’t amused.”

Randy repeated, “Campbell to Jackson for the winning TD.”

He smiled.

They arrived at my front door at a little past eight o’clock on a Saturday night. I’d been expecting them for a couple of hours. The Stallion had called me nearly three weeks earlier to tell me he was coming up from Sarasota to visit Sherman and wanted to see the old teammates.

Having been out of town on the day of his arrival, I was last on the list. There are several of us who played at Auburn together and who live within a few miles of each other; Ken Bernich, an All-American Linebacker; David Williams a standout linebacker; Chris Wilson, a kicker; and Carl” Hollywood” Hubbard, another linebacker. Being last meant we could have more time to catch up.

When the doorbell rang, I limped over to the door and there they were. Their grins were as big and wide as mine. “TG” they both called out.

“Sherman and The Stallion,” I returned. They could barely get through the door before we were all over each other hugging, grinning and laughing.

As teammates we had played football together at Auburn University in the 1970s. Those had been good football years at Auburn. During my four years on the team, we finished #5, #8, and #9 in the country; never had a losing season and three of the four years we never lost a home game. It was good times.

The guys ushered themselves in and exchanged pleasantries with my wife, joyce, and then it was our time.

The last time we’d been together had been a couple of years ago in the restaurant at the Auburn Hotel and Conference Center one Saturday night after an Auburn football game. That night we exhausted all our stories and begin to delve into the “do you remember game.” Names like Pete Retzlaff, Warren Wells, Willie Galimore, Sonny Jerguson, Homer Jones, and other old professional standouts brought back fond memories from our youth. Tonight, I was sure, would be just as much fun.

The Stallion, Ken Calleja, a running back was originally from Detroit, Michigan before moving to Sarasota, Florida. He was one of maybe less than a half dozen northerners on the team. Yankees, the other guys called them. Of Italian descent he was nicknamed the Stallion because of his sleek physique and his long flowing jet black hair. He was a handsome stud and he knew it… so did all the girls on campus.

The other half of the duo, Sherman Moon has health issues but other than being a bit thin you’d never know it. He is still Sherman, one of the best guys you will ever know. “Good as gold” is the description I use. If someone says they don’t like Sherman, get away from that person as fast as you can. Something is wrong with him.

Sherman, Ken and I were all ball handlers, the glamour positions on the football team. Ken was a runner. He’d run the hurdles in high school track and ran with a prance.

Sherman and I were receivers and occasional runners. With those positions comes a cockiness that is needed to run headlong into a defense of eleven angry men and think that you can out maneuver and out run them all. Yes, we liked ourselves.

Oftentimes after practice we’d brag over how good we’d been that day in practice. My favorite was “I was so quick out there today, I scared myself.”

Sherman and the Stallion were both “Florida Boys.” Florida Boys in that day and time was code for being soft. We were still playing football in the dark ages of less than ten passes a game, and “no pain, no gain,” “suck it up like a man” and “get your game face on.” With many small town Alabama roughneck boys on the team, the Florida Boys received undue criticism. The coaches were tough on them. But if you wanted to play, you paid the price.

It wasn’t long before the stories began to flow.

Ken was up first doing his Coach Claude Saia impression. Coach Saia was the Auburn running back coach. Stallion has him down pat. He not only sounds like Coach Saia, he can stand like him, walk like him, and mimic his facial expressions. One of our favorite lines from Coach Saia as he directed his running backs was to tell them, “You got to stay on Avenue One.” He never explained where in the hell Avenue One was, but all the running backs were expected to know. Ken could arch his hips like Coach and deliver that line better than Coach himself. I almost slid off the couch I was laughing so hard.

Sherman and Ken had come to Auburn at the same time, a year behind me. They were close throughout college and had many of their misadventures together. When Ken started to tell the story of the ballplayer who entered Auburn on what Ken called

“Double Secret Probation,” Sherman had to help him get the facts straight.

I interrupted, “What is double secret probation?” Apparently this young man’s grades were so bad in high school, that he’d been admitted into the University on Double Secret Probation meaning no one would admit to knowing how he got in but he only had one semester to prove he was college material and that did not include the football field.

The young man did not fare well during his one quarter on campus and decided to assist himself with his grades. His plan was to enlist some of his teammates, steal a professor’s test and secure for himself a great test score. He stole the test and scored 98 out of 100. It was however followed up by the F he was given for cheating. His double secret probation did not last the entire quarter and his teammates in the meantime received F’s as well for cheating. I had known the guy before he left, but didn’t know about the double secret probation or his misadventure in breaking into the professor’s office and stealing his test. I never knew what happened to him. I just knew that one day he was gone, never to be seen again.

We took turns talking about our offensive coordinator. Big Gene Lorendo, stood about 6’4” and was north of 250 lbs. His deep baritone voice struck fear in freshmen and sophomores. He was hard nosed and could boom out your name in such a threatening manner that you would check your football pants to see if they were wet. Since we were all on offense we all played for him. If Sherman went out for a pass, missed it and came back limping, we knew what was next. “MOOONNN ” he would bellow. “Don’t give me that hurt ankle shit, Moon.”

I often tell people as a sophomore, he changed my name from Thomas Gossom, to “Got Damnit Gossom.” You could hear him all over the practice field, screaming, “GOT DAMNIT GOSSOM.”

The stories flowed until well past midnight. I’m still laughing now several weeks later.

That night whatever issues we had with health, family, finances, or just life were forgotten as we fondly traveled back into a time that had shaped the rest of our lives. The memories in some cases were actually better than the actual time spent on the field.

After midnight the guys finally took their leave. I tried to get them to spend the night. They declined. They needed to get to Sherman’s. I thanked them for coming, for the memories, for the times, for the friendship. At the door, in between handshakes and hugs, we proudly spoke words we never would have as young, cocky, virile athletes. “I love you man, ” flowed from our mouths. “Love you too,” we all repeated.

What a special night!