What Are You Doing With The Rest Of Your Life?

Best Gurl commemorates 30 years of business in May 2017

Founder Thom Gossom Jr. “looks back” in a series of blogs

It was as though the cover of Esquire Magazine was talking directly to me.

Esquire Magazine

Americans at Work: A Special Year-End Edition

December 1986

What Are You Doing With the Rest of Your Life?

I took the question personally. What was I doing with the rest of my life? By May 1987, I not only had the answer, I had acted on it. This month, May 2017 marks my 30-year anniversary as a business owner/creative entrepreneur. It’s a path I carved out for myself; and what a ride!

I began the year 1987, my 35th on the earth, with the idea that I would go out on my own, work for myself. I liked the work I was doing. It was better and more sustaining than trying to make someone’s professional football team, which I had done the years right after college. I particularly enjoyed a friendship with the people I worked for. They were interested in assisting me make the transition from athlete to a career in management. They were great to me and taught me lessons I still employ today in my work. But I had an itch I needed to scratch. I was sure I wanted to start my own PR/ Communication firm using the lessons I had learned from 8½ years in management at BellSouth/AT&T. I was sure, but not sure enough to act on it or tell anybody.

What Are Your Doing With The Rest Of Your Life? pushed me out the door.

The last four years at BellSouth had been a cram session in executive management, executive support and what we called “managing up,” Managing the senior executives’ daily lives, which helped to make them successful in their careers and allowed me to be successful at my job.

As a PR manager, my job was outside the company boundaries. I worked on the President’s staff at one of the smaller BellSouth companies. My boss, a district manager, was the President’s and Vice President’s main man. He got things done. I learned from him.

Often times, I dealt with media, the press, other industries, community interests, and just managed a hodge-podge of initiatives that moved the stakeholders’ interest to the next dot. I was good at it. When I was asked what exactly I did, I liked to say, “I get things done.” But…. there was that itch. And it needed scratching.

There were lots of loose ends to tie up. As a matter of fact, they were all loose ends but somehow they quickly came together. There was the talk with my boss at the company. It took nearly three months for it to finally sink in that I was serious. Finally, I wrote the resignation letter and set the date for May.

There were hurdles to jump over. There were always hurdles within the job and outside of it. Inside the company, I would have to tell the people who had been very good to me that I wanted to leave. Outside the company, I would have to tell family and others that I was leaving my good job to speculate, to go out on my own. After I crossed those hurdles there were the rumors around town that I had been fired.

No. Sink or swim, I was leaving on my own. I only had to convince one person. Me!

What are you doing with The Rest of Your Life?

I was sure. My 92-year-old dad now says, “It worked out.”

I quickly moved to secure clients. My previous employer initially hired me. We continued that relationship for the next 13 years. I signed up two more utility clients and ran my high school friend’s campaign for Birmingham City council and hired a staff. We were rolling.

Looking back, it’s been an incredible ride. It was definitely a leap of faith. The company Thom Gossom Communication, inc. went through several versions of itself but it always sustained me, and later my loved ones; and has eventually morphed into Best Gurl, inc. I ended up dividing my time between the business and later on working fulltime as a professional actor and writer.

Working for myself has meant working much longer hours, being on the road most of my adult life, less time at home and less security than most. It has also meant adventure, learning about different businesses, meeting people, more control of my financial situation and establishing friendships, I never would have had. I’ve worked in 15 states and all across Canada. I’ve met many wonderful people along the way; stars in both industry and entertainment.

The work has allowed me to make contributions to the communities I’ve lived in, give back to my alma maters, serve as a role model to others and selfishly explore my creative side.

The framed Esquire Magazine cover now hangs on the wall over the desk in my office. Thirty years later, it continues to ask me, What Are You Doing With The Rest Of Your Life?

The immediate utterance of “Oh No” spilled from my mouth when first hearing the news of Wayne’s death. It was not long after that I began to smile, and continue to do so when I think of Wayne “Baltimore” Bracy. Baltimore left us on March 21.

The blogs and postings I’ve read by others speak of a Wayne I did not know, the life he lived after leaving Auburn University. Apparently, he was a dynamic high school basketball coach, for 20 years. He took his team, Deshler High School on five trips to the High School Final Four during his final six years with the team. He was described as very intense and passionate about his coaching. Those who know this part of his life say he was a mentor to a lot of young men and young ladies. All of that sounds like him from earlier days.

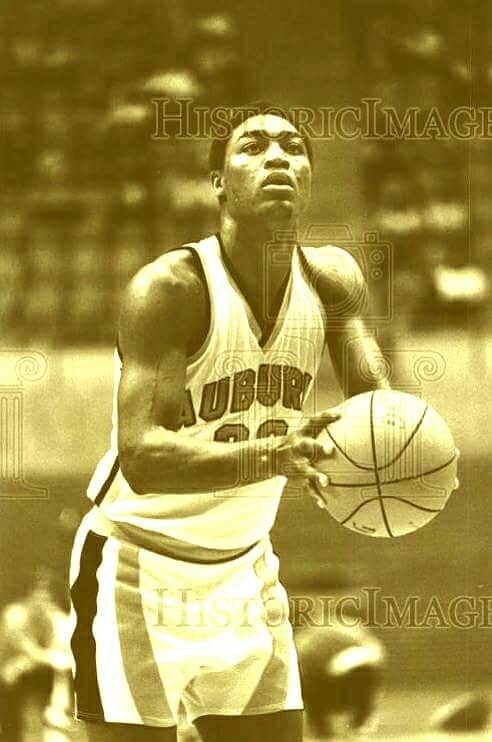

I met Wayne in 1974 at Auburn University where he signed to play basketball. Wayne joined a team of stars, two of which, Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell, went on to be stars in the NBA.

1974 was a watershed year for Auburn University and black athletes. In 1970, when I started at Auburn, there were only three black athletes between the football and basketball programs. By 1974, there were 14 black athletes between football, basketball, and the track team. As Sam Cooke sang, “A change gon’ come,” and it was on the way.

Being a senior during Baltimore’s freshman year, I got to know him and acted as a guide - particularly to the young players who were in their first integration experience. Coming from an all-black environment to a nearly all-white one was an adjustment some could not make. Baltimore was a good student; he made the transition.

During that time, so many basketball stars were signed that it was inevitable someone would have to step aside for others, or adjust their role for others to play. Baltimore would not become a big basketball star scoring-wise, with Eddie Johnson and Mike Mitchell scoring 20 and 18 points respectively and Gary Redding scoring nearly 15. For his career Wayne scored 4 points per game, but he was a contributor, a standout. Some guys become standouts because they can set one role aside and move into another.

Wayne’s role changed. He was a fundamentally sound player who learned from the legendary coach Willie Scoggins at Hayes High School in Birmingham. His strength was guiding the team from the point. Much like Magic Johnson, Wayne could impact the game without scoring. He became a defensive stopper. The other team’s best scorer? Give him to Baltimore. He’d shut him down.

“I have a style all my own,” he told me, referring to his style on the court and how he dressed off-court also. He was stylishly dressed as he walked to class, journeying into his new world. He named himself Baltimore. As long as I knew Wayne that’s what I called him.

As a senior, I tried to have a special relationship with the freshmen. Baltimore and I developed one. I admired the way he carried himself. He had an impact on me.

He was studious, strong, and lived life the way he played defense…man-to-man. Baltimore made an impression on me that has lasted more than 40 years. That’s quite an impression when you consider I haven’t seen him in nearly 20.

The Big O is gone.

My friend. My teammate. The man who helped me through the biggest cultural change of my life is gone. James Curtis Owens died today, March 26, 2016. I knew it was coming. We all knew it was coming. But knowing and living beyond it leaves a hurt and pain deep down in my soul.

I first saw the Big O on a Friday night at John Carroll Athletic Field on Montclair Road in Birmingham, Alabama. I was a junior at John Carroll High School, playing my first full year of organized football. We were a small, rag tag, undersized bunch playing about two classifications above our ability and size level. We didn’t win very often.

The opponent was Fairfield High School. They were good. They had a starter named James Owens, who would later sign with Auburn University, becoming the first African American to integrate a major state university in Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi… the Deep South. Now, he was warming up across the field from me. A running back, he was tall, lanky and wore a horse collar around his neck. He was about 6’2” and weighed close to 210 pounds. He looked dangerous. Ready to kick some you know what!

Our coach had warned us about him. He’d then gone on to tell the lie that coaches tell outmanned teams when they are about to get slaughtered by a bigger, faster, better team with bigger, faster, better players.

Referring to Owens, our coach said, “Hey! He’s no better than you. He puts his pants on one leg at a time just like you do.”

We all knew that was bullshit. Putting his pants on like we did had nothing to do with playing the way we did. This guy was All-State in football and track. He ran the 100 hundred-yard dash and threw the shot-put. He was a monster. I was glad as hell I wasn’t on defense.

It wasn’t pretty. He left carnage on the field. I don’t remember the score but it wasn’t close. After it was over, I watched him walk off the field where he had dominated us. Having integrated Fairfield High School football he was now heading off to be one of the first blacks in the Southeastern Conference.

Two years later, I would join James and Virgil Pearson, also from Fairfield, and Auburn’s first African American Athlete, Henry Harris, at Auburn University.

As a basketball player, Henry often travelled in different circles. For Virgil and me, James became our Daddy. We nicknamed him “Daddy O.” He was strong like our fathers, but gentle towards us, who had followed him. We not only respected him, everybody, on and off the field and in the athletic complex, held James in high esteem. Integration made things socially awkward but everybody respected James for his quiet, dignified courage. That respect lasted all of his life.

Our special friendship lasted from 1970 until his death. Like close friends we drifted apart throughout the seasons of our lives but we always found each other again because of the love and respect we had for our shared experience.

Henry left Auburn University after his senior basketball season. Virgil left his sophomore year, looking for a different experience. For the next two years on the varsity football team It was just James and me, as athletes of color. For the rest of his life we always relived that experience.

Between us we realized there was no one else in the world who shared that loneliness, that moment in our lives where we carried the pail of integration uphill without much assistance from those who could have helped us along. Those times were about providing for those whom would follow. We knew that. It kept us going.

James kept me grounded. He talked me down many times when, emotionally, I was way over the top. Over time, we embraced our teammates and they embraced us with that special bond that comes from the shared experiences of being teammates and winning games. During the two years when James and I were the two black pioneers on the team, we won 19 games and lost 3. We were a part of something bigger than us.

Throughout the decades that followed we talked a lot about those times. We always circled back to that experience. What had been a painful part of our lives had become, by the 21st century, a memory of achievement, a gift that we gave to all who followed at our university, not just the black athletes. We also grew to love our teammates and they loved us back. Today we are teammates for life. It ‘s more than a slogan. We live it.

James is an Auburn University icon. He doesn’t need for me to tell everyone about his contributions. Look around the university and you will see his accomplishments in the faces of the young men on the football team, the basketball team, the track team, the baseball team and in the faces of the young women on the softball team, the basketball team and all the other sports that did not exist before integration.

He will always be remembered for what he gave to Auburn University, the state of Alabama and college football. I will always remember him as my friend.

The news of death travels at Internet speed. I found out about my friend “Wash” while trolling along on Facebook. He’d died that morning.

“Book” was the type of guy you didn’t envision dying. Not suddenly. Not of pneumonia.

There is no single descriptor for “Booker.” Just like his many different friends called him by the many variations of his name he was a character, one with deeply held convictions of righteousness and caring for those with less than.

“Try and do as much right as you can in the world,” was one of his quotes on a You Tube interview you should see. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nguzYcltZOk).

He tried. He was a child protester in the Birmingham Civil Rights movement at age 14. At 18, he did his duty in Vietnam. He was a foot soldier all of his adult life for human rights. He was a political activist and an agitator. Man, he’d agitate the heck out of you. He liked getting up under your skin.

We traveled in different circles. Me, in the upscale world of shirts and ties, “Book” in his overalls, white T-shirt and a hat sitting astride his head, grinning. Always grinning.

Our common ground was a heart for humanity, a love of poetry and drama and bicycles. Poetry and drama unites the unlikeliest of humans. Joins us through the power of words. Joins us through our mutual humanity. We shared that. Our love for humanity expressed in the words of writers, actors, poets, on stage, in church, and on the street.

Bicycles. We would ride up and down the hills near Shades Crest Road when I lived in Hoover, Al. On those rides we debated our mutual humanity and how best to serve others. We always agreed on the expected outcome. Getting there would sometimes lead us down different paths.

The last time I heard from my friend was through a mutual friend, Judge Mike Graffeo. They both live in Birmingham. I was in Los Angeles. It was a call I couldn’t answer for whatever reason of importance at that time. Mike left the message he was with Booker and they were giving me a call. But they would be gone in a few minutes.

On his You Tube interview, Booker leaves us all a message.

“ If you truly believe that every human being is important. …that the greatest thing on earth is another human being and that the greatest thing on earth is our collective mind.

…And if we could ever tap into that, ever just realize that the only things holding us back is us.

…If we could pursue peace like we pursue war. We would already have cured cancer and be a thousand years ahead of where we are now.

Try and do as much right and as much good as you can. Try to spread as much love and joy and peace in the world as you can.”

The words of Washington Booker III, born January 20, 1949, died January 20, 2016.

Reflecting on Father’s Day, I think about the man for whom I am named and realize how much I lucked out. Man, did I luck out!

I never looked outside our home for a hero or a role model. I never looked to sports figures. My guy was living in the house with us.

Daddy turned 90 this past April. He has a pacemaker and he can be testy but other than that he’s in great shape. He drives his truck, walks in a nearby park, works in his yard and attends church regularly. Watching him as I grew up, I knew he was what I wanted to be as a man.

Daddy accepted responsibility. Born into a sharecropping family in Elmore County Alabama, he grew up poor. He was forced to drop out of school early and often to work in the fields. It’s one of his regrets. “I was a good student,” he tells me. “I was good in arithmetic.” To this day, he can add and subtract numbers in his head if needed. He got his GED after a stint in the army.

He met my mom and began the journey that produced my two sisters and me. He gave his all to us, his family. I was and am his only male child. He taught me. He taught me about work, doing what needs to be done. He taught me about integrity, a man’s word is his bond. He taught me about giving, being there for others whether they were related to you or not. He taught me not to dwell on the negatives of a situation, but to realize I was passing through on my way to somewhere else. He taught me how to love your wife, unconditionally.

When integration came to the South and directly touched our lives, in one fell swoop my life surpassed his in terms of opportunity, unchained boundaries, and new journeys. Although fearful for me at times, he let the reins go. When my new world took me in directions that he could not fathom or wanted to travel in, he let me fly, never wanting to limit or hold me back from the good things I might discover on the journey. He tells me now, “I was afraid for you being in a world I knew nothing about. I’d never had a white friend in my life.” His world was different. But he did not attempt to color mine.

He learned about football when he was a baseball man. He bought us a home, then a bigger one when our family grew. He came to my games when often times he was the only black face in the crowd. He put himself in awkward situations in my new world, where he often felt ashamed of his lack of formal education, but he knew he needed to be there for me. Tears fall from my eyes as I write this because he gave us so much of himself and kept so little for himself.

The story I tell about my dad that makes me most proud, and there are many, is “the snow tale.” We had a massive snowstorm in Birmingham, my hometown, and the city was paralyzed. As an adult I had moved into my own home but kept close ties with Mom and Dad. Knowing they lived on a hill and it would be virtually impossible for them to go anywhere, I called my mom and we chatted about the snow and family matters. I asked to speak with my dad. She said, “He’s gone to work.”

Daddy worked in a pipe shop, American Cast Iron Pipe Company (ACIPCO). I asked, “how?” knowing he could not drive his car up the sloped driveway nor on the closed roads between his home and the pipe mill, which was a good thirty-minute drive from his house. Mom responded, “He left here walking.”

“You don’t work they don’t pay you,” he always told me.

That evening in the local newspaper, there was a shot of a lone figure walking along the railroad track in the snow heading toward the pipe shop, a solitary man doing what he had to do. It was my dad. “You don’t work, they don’t pay you,” should have been the caption.

Daddy worked. He worked at the pipe shop for thirty-five years. He worked a second job at a janitorial service for many years, and he had a “side hustle” as a plumber to pick up the extra money it took to send us to private schools for twelve years.

Because he worked so much, there was little to no time for us to play catch or do the Father-Son things that I might have wanted. But I wanted to be like him. And it wasn’t long before I started down that road of, “doing what it took.”

Daddy left home about five every morning for his 6:00 to 2:30 shift at ACIPCO. He returned around 3:00 in the afternoon before leaving again around 4:30 for the janitorial job. He returned home at 10:30 that night. Before long I was like him, leaving home at 6:15 am to catch the two city buses for the private Catholic High school across town, where I had integrated the football team, and returning at nearly 9:00 every evening after football practice and catching the two buses to get back home. Sometimes we would chat for thirty minutes or so before getting to bed and doing our thing again the next morning.

We talk now and he often tells me of the things he didn’t know when I began my journey into integration, sports integration, big-time college sports, professional sports and the world of white-collar work. He says how he wished he could have done more. “I never had any money to send you when you were in college,” he regrets. “I wish I had known more, so I could have helped you when you were struggling with your coaches and things that were not fair. I didn’t know,” he laments.

I tell him, “Daddy you taught me how to be a good man. It’s the best thing you could have ever done for me.”

The first time I told him I loved him I was well into adulthood. It caught him off guard. Expressed sentiment was not a part of our lives. It was and still is uncomfortable for him. Daddy showed his love for my sisters and me in ways that words could never express and for that I am forever grateful.

For my dad, Tom Gossom, I Love You, Happy Father’s Day.

Got another Birthday coming! I‘m tingling! My birthday does that to me. I love my birthday! It’s fun!

It goes back to childhood. My mom made our birthdays special. It was your day of celebration. There were few big parties. But from morning ‘till bedtime, it was your day. Mom baked the cake of your choice. Dad froze your favorite flavor of homemade ice cream. I’m a homemade vanilla and chocolate cake with pecans guy. OMG! The family sang Happy Birthday. It was your day!!!

1/21 is my day. Every year.

This year I’ll work the weekend before my birthday and take my day, Wednesday, off. My ideal day: Do the gift thing with joyce, walk the beach, a good bike ride, sit in the backyard and reflect; appreciate the “Happy Birthdays” that come my way, an afternoon movie, and dinner at Pandora’s occupying “The Gossom Booth” courtesy of the owners, The Montalto’s.

At 7:30 pm, I will think of my mom. I was born at 7:30 pm. Thanks Mom.

I’m smiling, thinking about it.

Last year on my birthday, I visited the doctor’s office for some routine thing.

The “I got an attitude,” receptionist demanded of me, “Birthday?”

“One Twenty-one,” I answered cheerily.

“What year?” she snorted.

“What’s her problem?” I’m thinking.

“Every Year,” I answered.

She didn’t appreciate the humor. I let that be her problem.

1/21 is my day. Every year.

I love what I do. It’s fun!!! I’ve been doing it for a number of years now and it only gets better. Whether it’s acting for television, writing a collection of short stories, producing a documentary, consulting with a client or making a speech before hundreds of foundation board directors. It’s all a blast to me. Fun!! Most of the things I do today in the early stages of my career I did them for free. That’s how much I enjoy them.

So why was I taken aback last week when, during a Q and A session after a speech, I was asked, “What does it feel like to be a celebrity?” I hesitated. Had to think. I was kinda embarrassed. You see, I’ve never thought of myself as a celebrity. To be a celebrity, I always thought you have to have an entourage. I’ve never had an entourage.

But for my next trip I decided to try out the celebrity thing. I flew to Los Angeles rented a car and drove to the Palos Verdes Peninsula for a speech the next day.

I was given a suite in a resort overlooking the Pacific Ocean, with walking trails into the surrounding mountains. Gorgeous! Even though I didn’t have an entourage, I allowed myself to feel very celebrity like. As I walked along the walking trail, people spoke to me, and gave me big smiles. I checked in with the client who had purchased my services and they made me feel like the second coming of Brad Pitt. They were all over me, “Do you need…?” Someone came up and asked me for an autograph and I hadn’t even spoken yet. I thought, “Okay, maybe I am a celebrity.”

Later that day, enthused with my newfound celebrity, I blew the audience away with a forty-five minute keynote address for nearly 450 people. They were generous enough to give me a standing ovation. Afterward, there were questions and answers; people lining up for photos that I knew would go straight to somebody’s Facebook page. There were autograph and business card requests. Man, I was feeling like somebody! After an hour of celebrity-hood I retired to my suite, called my wife, and wondered why if I was a celebrity, she kept telling me about issues at the house I would need to solve when I got home. Things like, the motion detector floodlights not working and getting the cars serviced. I reminded her that celebrities have “people” to handle those kinds of things. She laughed. Reminded me that she did have “people.” Me. Where in the hell was my entourage when I needed one?

My celebrity-hood ended at that point.

Without an entourage, I awoke at 4:00 the next morning, packed up the rental car, and headed to the LA airport for a 6 am flight. Who schedules a 6 am flight for a celebrity? I sure as hell didn’t do it. In the airport, no one recognized me or gave a hoot that I had rocked the Association of Governing Boards’ annual conference at the Terranea resort the day before. I was just another passenger. Still, my first class seat reinforced my celebrity-hood until the lady in front of me who obviously didn’t know I was a celebrity, laid her seat back in my lap damn near pinning me into the seat behind me. “Damn, woman don’t you know who I am?” I wanted to say. “Man,” I thought. “If I had one of ‘my people’ here with me, I’d tell them to handle this small fry sitting in front of me.”

Landing in Houston, my celebrity star not only faded, it lost all luster.

Because of an ice and snowstorm, across the country, my connecting flight was cancelled. I was directed to a nearby hotel. After being constantly assured for an hour and a half that the hotel shuttle was on its way, while standing in twenty-degree weather, I took a taxi. “Damn, Don’t they know I am a celebrity?” I thought.

Believe me, nothing from that point on was befitting a celebrity. Fifty-four ninety-five was the room cost. Need I say more? It was musty and uncomfortable. The funky heater would have made me laugh if it wasn’t twenty degrees outside. I sank onto the floor when I sat on the couch. My electronic key would never work more than once. If I needed to get back into the room, I would have to go to the front desk where there was never anyone present, and ring the bell. “What’s wrong?” would be the response. “Nothing,” I would answer, “other than I need to get in my room.” If ever I needed an entourage, being stranded in Houston would have been a great time to have one.

Last year, I did nearly 125 days on the road. It’s part of the gig. None of those days turned out to be as hectic as the twenty-four hours in Houston. I reminded myself of the gangster Hyman Roth’s admonishment to Godfather Michael Corleone in the movie, The Godfather. Roth tells Michael, “This is the life we have chosen.”

Upon landing at home, finally, “my people” (my wife), were at the airport to greet me. As usual she had her smile on. She gave me a big hug and said, “Sorry you got delayed in Houston. Your agent called and they want you to shoot next week in Charleston.”

I smiled back and asked, “Can you go with me?”

“Sherman is Sherman,” I accidentally coined the phrase when describing, to a former Auburn teammate, how our mutual friend and teammate Sherman was doing. Immediately, the teammate understood and giggled. Everyone who knows Sherman understands. Keep reading . . . you’ll understand too.

I’ve known Sherman Moon since 1971. In those days of yesteryear, we were competitors for the same position on the football team at Auburn. We remained competitors on the field, but friends off the field. Forty years later we lived one street from each other. Our visits consist of football debates, reunions with teammates, parties at our neighbors’, and enjoying Sherman’s BBQ. The man can throw down on a grill.

Sherman, then and now, always has a smile for you.

You see; with Sherman the glass is always half full. Smiling, laughing, talking, talking, and talking until you reluctantly have to interrupt or ask for a break.

“Oh, Okay TG,” he’ll say, and relinquish the floor for a few – a very few – minutes before jumping back in. He’ll throw his head back and take you on another one of his verbal journeys. Upbeat, head held high, and fun. That’s Sherman. Rain or Shine. Sickness and in health, stage four cancer not withstanding. My phone chimes and there’s his familiar voice on the phone, “Hey TG, what you up to?”

Sherman beat prostate cancer. He got ahead early in that game, recovered, and came out with a victory. The carcinoid tumor he’s been battling for the last three years has proven to be a booger that, even Sherman has to admit, has tested his mettle. The cancer has metastasized into his stomach, liver, and lymphatic system. Doctors in the US have thrown their hands up and cried, “No Mas!” But you didn’t get to be a teammate on the Auburn teams of ‘72, ‘73, and ‘74 without a lot of courage and fortitude. We’ve never backed down from a good fight.

I have not once heard him complain. I’ve not once seen him in a bad mood.

Several former teammates, who have occasionally run into him, call me and ask, “Is Sherman still sick?”

“Yes,” I reply.

“I saw him, and he was as upbeat as he’s always been,” they counter.

“Sherman is Sherman,” I respond.

Sherman says, “I have Cancer. Cancer does not have me.”

My friend Sherman is on his way to the Netherlands for treatments that, over the next few months, will cost him upwards of $70,000. With all the debate about Affordable Health care in the US, there is little doubt that remaining healthy and finding cures is expensive. In Sherman’s case, it has cost him dearly. He and his wife have lost their income and their home. His final chance at a Hail Mary pass, to regain his health, needs assistance.

Sherman’s teammates and friends are lining up at his side.

Sherman reluctantly agreed to have his story told and to have others solicit funds for him. Nineteen thousand dollars flowed in instantly from family and life-long friends. Next up, was a benefit golf tournament that included a dozen former teammates, some who had not seen him in forty years.

Teammates drove to Florida’s Fort Walton Beach from Mississippi, Tennessee, Central Florida, and Auburn, AL. Sherman made a brief appearance and took pictures with his friends. Then he took off for the airport, leaving for his trip to the Netherlands and the first of four treatments. His teammates and other golfers raised another $8,000 that day.

In Sherman’s honor, we laughed, reminisced with some great Sherman stories, and realized how special we are that Sherman came into our lives. Those who hadn’t seen him in many years marveled at how fun, positive, and upbeat Sherman was.

Just like always.

Sherman is Sherman.

**Want to support Sherman and Vicki Moon?**

Send donations to:

Sherman Moon

PO Box 2077

Fort Walton Beach FL 32549

Or contact Sandy North:

sandy_north@earthlink.net

Birthdays for me have always been celebratory. From my time as a curly-headed grinning youngster, to my memorable 21st, 40th and 50th birthdays. They’ve always been special.

Today’s celebration is also reflective, A look back, over the journey of things seen, lessons learned, and paths crossed.

I’ve jokingly talked about the uniqueness of this birthday. I’ve said to friends, “Think about it, President Barack Obama’s Inauguration, Martin Luther King’s Holiday and my birthday all falling on the same day.” Wow!

Do I feel special? Yes I do.

A beneficiary of Dr. King’s legacy and a forerunner to President Obama’s “he’s the first African American,” to do this experience, my reflection leads me back down history’s path. True history and truth are the scorekeepers for legacies. They record who is right and who is wrong.

Dr. King more than “having a dream” ushered in changes in social and economic morality in the United States. His sermons and speeches resonate today as moral, guideposts for ethics and character.

Annually, I read from A Testament Of Hope, The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King. The book, an inspiring work is a collection of King’s speeches on nonviolence, civil disobedience, and social policy. My favorite is The Drum Major Instinct, delivered from the pulpit of Ebenezer Baptist Church on February 4, 1968. The lessons are “fitness over favoritism” and “servant leadership” (“he who is greatest among you shall be the servant to all”). I have been honored to perform these words from Dr. King’s works. I can think of no higher honor.

The praise for King did not come easy. The criticism and stinging arrows were scary and led to his assassination. He was mocked, “a communist,” “a socialist,” “…he hates America.” “An outside agitator.”

Obviously, they were on the wrong side of history.

I wonder about President Obama? The personal attacks on this President have been different. Hate filled. My friends who happen to be white, whether Republican or Democrat, liberal or conservative, tell me of the hate filled stories about this man that are shared with them that those same “ friends” don’t feel comfortable sharing with me. My friends tell me if they defend their points of view with intelligence and fact, the conversation becomes a treatise on” treason” and “the white race.”

George W. Bush was a bad President, most agree. His record on the economy, United States security, international relations, and other key indicators verify that. Yet there was never the personal hate this President is subjected to. Surely, if raising taxes and the deficit were the sole issue, Ronald Reagan would no longer be praised.

At a recent football reunion, two ex-teammates were somewhat embarrassed at their own words and actions as portrayed in my book Walk-On, My Reluctant Journey to Integration at Auburn University, a look at my personal sports integration of major college football. Today, they are fine gentlemen, but back then they reacted to me out of ignorance and lack of exposure. They listened to false information designed to divide people and protect economic interests. I’m sure today, it’s embarrassing.

In my presentations and speeches, I often get the audience to mentally travel along with me back to the days of southern sports integration. If they are old enough, I ask them to examine their own feelings of who they were at that time. I then ask if they would want their grandchildren to have known them back then. I ask whether they were on the right side or the wrong side of history.

Many choose to lower their eyes no longer willing to make eye contact, their action a telltale giveaway to their answer. I imagine it’s not a comforting feeling to know that you were wrong, because of your own ignorance and your own unwillingness or laziness in searching out the truth.

Finally and for my birthday, ask yourself this question; Thirty years from now, will you have been on the right side or the wrong side of history? Will you be able to look those who come behind you in the eye or will you lower your eyes in shame?